Every Halloween if I’m able to I like to write an essay on one of the great horror movies. This particular one is very important to me in part because it’s the specific movie that turned me into a horror fan. I’ve written about it before but here I try to get at both why I still love it and how it speaks to me about the world today. Hopefully I’ve done it justice. Happy Halloween, everyone.

Every Halloween if I’m able to I like to write an essay on one of the great horror movies. This particular one is very important to me in part because it’s the specific movie that turned me into a horror fan. I’ve written about it before but here I try to get at both why I still love it and how it speaks to me about the world today. Hopefully I’ve done it justice. Happy Halloween, everyone.

A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET begins either in the past or a dream. A montage plays inside a rectangle within the larger frame, in which the hands of Fred Krueger (Robert Englund, SLASHED DREAMS) construct what will be a major element of his iconography: his four-bladed right-hand glove. Maybe the thought at the time was that a horror movie couldn’t just jump out with a crazy weapon like that – they had to establish it.

The scene fades to black as the title comes up, and the next shot, of the blades cutting through fabric, fills the screen. We’re definitely in a dream as Tina (Amanda Wyss, FORCE: FIVE) runs from a white void into a flooded, steaming, labyrinthine boiler room where she’s stalked by Freddy, who calls her name, cackles, makes his (new?) claws squeal against metal like fingers on a chalkboard. Right when he grabs her she wakes up, escaping into reality, but she finds four slashes in her nightgown.

Tina is the canary in the coal mine for this premise that a man is haunting the dreams of teenagers and if he kills them in the dream they die in real life. Her friends have been having nightmares too, but it’s weird to tell people about your dreams in detail, so they haven’t yet put it together that they’re all about this same guy.

Still, Nancy (Heather Langenkamp, TONYA AND NANCY: THE INSIDE STORY) understands that her friend is upset. She and her boyfriend Glen (introducing Johnny Depp) come over to spend the night with Tina so she won’t be alone while her mom (Donna Woodrum, “Nurse #2,” one episode of Falcon Crest) is in Vegas with her boyfriend. Tina’s dirtbag boyfriend Rod (Jsu Garcia [as Nick Corri], GOTCHA!) also shows up to scare them and non-apologize for something he said at school, so Tina drags him into her bed. An inconvenient place to end up.

Still, Nancy (Heather Langenkamp, TONYA AND NANCY: THE INSIDE STORY) understands that her friend is upset. She and her boyfriend Glen (introducing Johnny Depp) come over to spend the night with Tina so she won’t be alone while her mom (Donna Woodrum, “Nurse #2,” one episode of Falcon Crest) is in Vegas with her boyfriend. Tina’s dirtbag boyfriend Rod (Jsu Garcia [as Nick Corri], GOTCHA!) also shows up to scare them and non-apologize for something he said at school, so Tina drags him into her bed. An inconvenient place to end up.

The ELM STREET sequels developed a formula of gimmickry in the dream sequences, complex set pieces built around a few basic character traits established for the dreamer. For example in part 4 Debbie (Brooke Theiss) loves fitness and hates bugs, so she dreams that she’s lifting weights and her arms snap off and grow into insect legs, then she fully transforms into a roach and gets stuck in a roach motel, which Freddy picks up and crushes. These are great showcases for the series’ incredible FX artists, and a big part of what makes it fun, but they’re not truly dreamlike – too logical to pass for the work of the human subconscious.

The dreams in Craven’s original admittedly seem to follow some artificial rules – they always start where the dreamer is sleeping – the bedroom, the class room, the bath tub – so that the characters and viewers can question whether they’re looking at a dream or reality. But I appreciate that they otherwise don’t make much sense. A random sheep passes by Tina in the boiler room, she hears babies crying, Nancy sees leaves blowing in the halls at school, a giant centipede comes out of a mouth, there are piles of slimy snakes. The dream image I’ve always related to most is when Nancy runs up the stairs and her feet sink into each step like she’s stuck in pancake batter or something. I often have a hard time moving in my dreams.

In Tina’s last dream Freddy grows long, crooked arms for no reason. Just to show off I guess. He’s a troll. He’s a little boy trying to gross out a girl. He literally says, “Tina! Watch this!,” then chops off two of his fingers and grins. So proud of himself. Same thing when he cuts his chest for Nancy to see maggots and green slime dump out. Oh, you did it, Freddy! You were disgusting! What an achievement!

In Tina’s last dream Freddy grows long, crooked arms for no reason. Just to show off I guess. He’s a troll. He’s a little boy trying to gross out a girl. He literally says, “Tina! Watch this!,” then chops off two of his fingers and grins. So proud of himself. Same thing when he cuts his chest for Nancy to see maggots and green slime dump out. Oh, you did it, Freddy! You were disgusting! What an achievement!

For my money Tina’s is the most disturbing death in any ‘80s slasher movie. The wounds appearing on her, the way she’s carried by an invisible force to the ceiling, gets dragged up the wall and across the ceiling, reaching out for Rod, then just flopping down on the bed, and there’s so much blood. And soon we get Nancy’s first dream, when she falls asleep in class and sees Tina in the hallway, standing there calling to her, zipped inside a transparent bodybag. She’s dragged down the hall, leaving a thick red stripe all through the school, down into Freddy’s boiler room.

After so many years I think I take the ingenious special effects of this first one for granted. I used to think it was so cool when I read about the rotating room (also used in BREAKIN’ 2) that they used for Tina’s death and Glen’s blood geyser. Now I concentrate less on how inventive the scene is and more on how brutal it is. You don’t get a jolt that strong in every horror movie.

Other than Tina’s two dreams, the point-of-view rarely strays from Nancy’s, so she’s even more a central focus than Laurie Strode was splitting screen time with Dr. Loomis in HALLOWEEN. Nancy has always been my favorite horror heroine, partly because of her tenacity in fighting back. In Men Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, the book that coined the term “Final Girl,” Carol J. Clover calls Nancy “the grittiest of the Final Girls.” She includes as evidence the climax where she sets traps for Freddy, pulls him into reality and fights him.

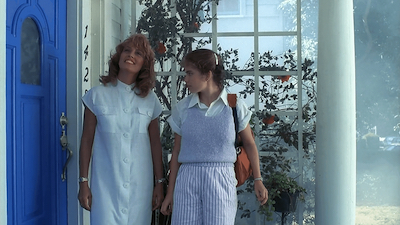

That ferocity juxtaposes well with her general appearance of girl-next-door sweetness. She doesn’t have a cool leather jacket or other horror movie symbols of toughness – she wears sweater vests and cute embroidered pajamas. But when Rod pulls a switchblade on Glen she fearlessly grabs his wrist and removes the knife from his hand. Later she’ll (temporarily) save Rod’s life by putting herself between him and her dad (a cop played by John Saxon, ENTER THE DRAGON, THE GLOVE)’s gun.

That ferocity juxtaposes well with her general appearance of girl-next-door sweetness. She doesn’t have a cool leather jacket or other horror movie symbols of toughness – she wears sweater vests and cute embroidered pajamas. But when Rod pulls a switchblade on Glen she fearlessly grabs his wrist and removes the knife from his hand. Later she’ll (temporarily) save Rod’s life by putting herself between him and her dad (a cop played by John Saxon, ENTER THE DRAGON, THE GLOVE)’s gun.

Outside of how she deals with this whole dream killer situation we don’t know that much about Nancy’s life. She likes The Police, the band (there’s a poster of them in her room). She thinks 20 is really old. She’s good at following instructions, judging from how much use she makes of the book Boobytraps & Improvised Anti-Personel[sic] Devices. She’s tough and smart but still enough of a kid that when she notices the line of her phone is cut and then it rings anyway she very earnestly answers, “Hello?” Like, who does she think is calling?

Glen is interesting because he’s mostly portrayed as a goofy jock, but he pulls a Wes Craven and tells Nancy all about “the Balinese way of dreaming.” (Oddly he has a stuffed condor in his bedroom, a bird Craven would reveal an obsession with decades later in MY SOUL TO TAKE.)

Watching this again so close after THE EXORCIST I see that Craven follows the idea of the mother trying to use science to help her daughter with what is really a supernatural problem. But the result is that Nancy pulls Freddy’s dirty fedora out of her dream right into the observation room at the Katja Institute For the Study of Sleep Disorders, in front of her mom (Ronee Blakley, NASHVILLE, THE DRIVER, A RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT) and the doctor (Charles Fleischer, WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT, ZODIAC).

Even then, Mom can’t accept what her daughter is telling her is going on. A guy being after them in their dreams, “That’s just not reality, Nancy,” she says. But soon Nancy comes home to find her in a bathrobe with a cigarette and a bottle of her favorite vodka, ready to confess that Fred Krueger was a child murderer she helped burn alive. She even took a souvenir: that glove that the movie so lovingly explained in its opening frames. Now it’s just wrapped in an old rag, stored away in the basement, not far from the Christmas decorations.

(By the way, she says “he killed at least twenty kids in the neighborhood.” At least twenty kids in one neighborhood? They should’ve demolished that place and started over.)

In his first non-porn film LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT (1972), Craven transmogrified Ingmar Bergman’s THE VIRGIN SPRING into drive-in sleaze, but tried to do the reverse, in a story about ordinary parents debasing themselves by enacting sadistic revenge on the sickos who murdered their daughter. In his second film THE HILLS HAVE EYES (1977) he similarly transposed an archetypal middle class family with literal savages – a violent tribe of mutant desert cannibals.

Here Craven borrows a trope from the world of DIRTY HARRY, DEATH WISH and VIGILANTE: the clearly guilty maniac given a red tape lifeline, smirking all the way to freedom, on account of them pesky bureaucrats and civil liberties and what not. “The lawyers got fat and the judge got famous, but somebody forgot to sign the search warrant in the right place,” according to Mom. So “a bunch of us parents” (perhaps jumping the gun in my opinion, there might have been other legal options) went and killed him, never imagining the supernatural consequences their choice would have for their kids.

So I think Craven had the then-buzz-topic of vigilantism on his mind, but the story is poetic enough to extend to many other meanings. All those years ago the parents did what they did, and they don’t talk about it anymore, so when Nancy starts describing Freddy and saying his name they pretend like they don’t know who she’s talking about. But pretending they never heard of him doesn’t help any more than burning him did.

To me that’s what it’s about: the parents’ generation failed, the problem has gotten worse, and they refuse to listen to their kids raising the alarm about it. That’s how it always is, right? With wars, with civil rights, with capitalism, and so many other things, the young people who care are talking to a brick wall. Climate change? Uh… who’s that? Never heard of him. The people in charge tried their way, they don’t know another way, and they refuse to recognize another way, or the need for one.

We don’t know if Tina or Glen’s parents (who are still together and live right across the street) were involved in killing Freddy – if they were, you’d think they’d have a conversation about it. (This must be awkward if you moved to town just a little too late.) Either way they’re no help. Tina’s mom only offers the advice, “You gotta cut your fingernails or you gotta stop that kinda dreaming. One or the other.” Glen’s dad (Ed Call, WALKING TALL) thinks Nancy is “a lunatic” and doesn’t want Glen talking to her.

I like that Nancy’s parents really do care about her, and are also wrong. Nancy’s mom eventually tells her about Freddy, but her dad admits nothing, handles it like a cop, accomplishes nothing but arresting the wrong guy and having him killed in his cell by Freddy.

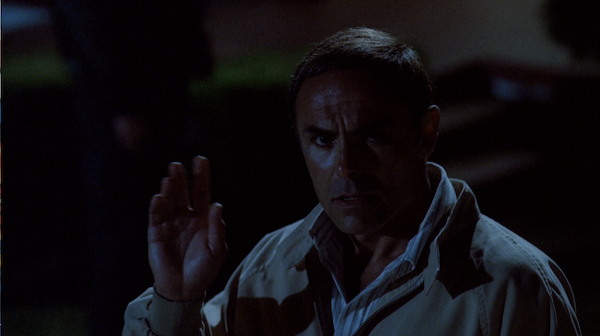

So Nancy’s on her own. She has Glen at first, but he falls asleep one time, falls asleep and dies the next time. She doesn’t see his death, but she knows it. She’s in her house, locked behind bars, she sees the police cars at his house, sees her dad pull up. A great moment is when he walks up to the house and you can tell by his body language that he’s realizing how bad they’ve whiffed it, if nothing else. And he thinks of Nancy and turns around and she dejectedly waves to him from the window, so he waves back.

Everything, everyone that was supposed to stop this from happening again has failed. He loves her but she sounds crazy. He doesn’t take what she says seriously. She’s on her own, even with half the police department right there, an officer watching her window for “anything funny,” while she builds deadly traps out of sledge hammers and light bulbs.

If we go by part 3, we know that Nancy survived to become a very young therapist, share what she knows about Freddy and die heroically killing him again. But this movie here doesn’t indicate that. I tend to remember the climax – turning her back on Freddy, refusing to fear him, to give him the negative attention he so desires – as the correct answer to the problem. And it does seem like the sort of thing Craven might preach. But in fact, within the movie, it does not work.  It seems to zap him away and bring back those she lost, but it’s too good to be true, dreamily sunny, and her mom is talking cheerfully about just deciding to up and not be an alcoholic anymore. The movie ends with Nancy and friends trapped in a Freddy-striped car and Mom yanked through a window in cinema’s very best riff on the CARRIE jump scare ending (which was also a dream, remember).

It seems to zap him away and bring back those she lost, but it’s too good to be true, dreamily sunny, and her mom is talking cheerfully about just deciding to up and not be an alcoholic anymore. The movie ends with Nancy and friends trapped in a Freddy-striped car and Mom yanked through a window in cinema’s very best riff on the CARRIE jump scare ending (which was also a dream, remember).

So it’s a cynical ending, like NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD or THE THING. The problem is not solved. The solution is not found. Freddy will come back again and again, and if he’s really dead now then it took the combination of a bad remake and the indifference of youth to finally kill him. Before that we had to keep trying, looking for new methods, digging up his body, killing him in 3D, and in our world, and with Jason. We couldn’t just call the cops, or turn our backs, we had to be more creative and tenacious.

Nancy’s mom told her, “You face things. That’s your nature. That’s your gift.” But she said it in the context of asking her to do the opposite, and that didn’t work. We need to use Nancy’s gift if we ever want things to change. I don’t know about you, but I do want things to change. Plenty of them. I’m about the same age as Saxon was at the time of this movie (trust me, I look younger) which probly means I should be the generation who needs to move out of the way, but I feel like we haven’t had our chance yet. We got skipped.

So we have work to do. We need to study the Balinese way of dreaming and shit, think outside the box, come up with a plan. You know how the song goes. Seven eight better stay up late.

Further reading:

I wrote about A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET (and all of its sequels) previously

Heather Langenkamp produced a cool documentary about being Nancy in a world where everyone loves Freddy

October 31st, 2023 at 9:37 am

Possibly the best horror movie of the 80s right here. It’d be a classic if it had just one of the absolutely iconic images it doles out every ten minutes.