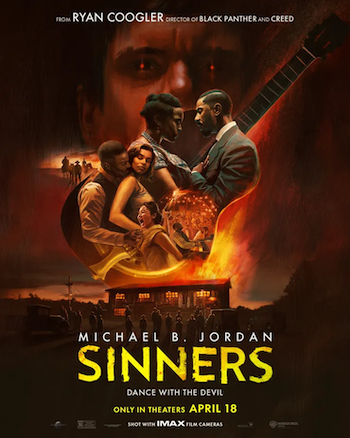

SINNERS is the first original story from writer/director Ryan Coogler. Not that it matters. After the true story of FRUITVALE STATION he added to fictional worlds and characters created by other people – CREED, BLACK PANTHER and BLACK PANTHER: WAKANDA FOREVER – but he sure seemed like a visionary to me. Working in such worn-out modern formats as “the legacy sequel” and “the MCU” didn’t stop him from constructing crowd-pleasing but deeply personal movies that transcend those categories.

SINNERS is the first original story from writer/director Ryan Coogler. Not that it matters. After the true story of FRUITVALE STATION he added to fictional worlds and characters created by other people – CREED, BLACK PANTHER and BLACK PANTHER: WAKANDA FOREVER – but he sure seemed like a visionary to me. Working in such worn-out modern formats as “the legacy sequel” and “the MCU” didn’t stop him from constructing crowd-pleasing but deeply personal movies that transcend those categories.

So shit yeah I was excited for him to do a vampire movie. Say no more.

It’s set in the Mississippi Delta, 1932. After some years of infamy working for Al Capone in Chicago, “the Smokestack Twins,” Elijah “Smoke” Moore and Elias “Stack” Moore have returned to their home town of Clarksdale. Both are played by Michael B. Jordan (WITHOUT REMORSE), and they’re introduced passing a cigarette back and forth. Later one tosses his knife for the other to stab a rattlesnake through the throat with. After that they’re often separated, but the illusion has been established seamlessly.

I like that it takes its time getting to the vampires, instead making me really invested in the twins’ plan to set up a new juke joint (with the generic name “The Juke”) in one day. They buy an old saw mill from a very iffy white man (David Maldonado, CAT RUN 2), then split up and go around to people with the resources and talents they need, friends from way back who seem a little bitter or suspicious and hesitate before they see how much it pays but still seem to love them. Family, basically. Cornbread (Omar Benson Miller, HOMEFRONT), for example, just wants to stay picking cotton on the field he share crops, but seems very happy once he’s there watching the door.

There’s this couple the Chows who own two shops in town, one on the Black side of the street and one on the white side. They’ll provide catfish and other food to go with the Irish beer and Italian wine the twins brought from Chicago. A classic Ryan Coogler scene is when Bo (Yao, TIONG BAHRU SOCIAL CLUB) sends his daughter Lisa (Helena Hu, “Girl,” one episode of Watchmen) across the street to get her mother Grace (Li Jun Li, BABYLON). The camera follows the kid all the way across, she takes Grace’s place behind the counter and then it follows Grace across to negotiate the price of painting signs. It’s the type of confident, almost swaggering filmatism I like from Coogler, like that long take ring entrance in CREED. It tells you about this family’s work and place in the community and imprints their daughter on us so it will be more meaningful when she’s mentioned later. The director of photography is Autumn Durald Arkapaw, who shot WAKANDA FOREVER and also THE LAST SHOWGIRL.

The twins each encounter an ex with lots of baggage. Stack runs into Mary (Hailee Steinfeld, 3 DAYS TO KILL) at the train station, in town for her mother’s funeral and sore that the twins didn’t attend, even though her mom delivered and practically raised them. But mostly she’s mad about Stack ghosting her when he left for Chicago. Now she lives somewhere else, passing as white, but her mother’s dad was half Black, and she’s more comfortable here. I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who looked up if that was really Steinfeld’s heritage (it is) and also learned that her uncle is Jake “Body By Jake” Steinfeld (HOME SWEET HOME). That part of her background the character doesn’t share as far as we know.

The twins each encounter an ex with lots of baggage. Stack runs into Mary (Hailee Steinfeld, 3 DAYS TO KILL) at the train station, in town for her mother’s funeral and sore that the twins didn’t attend, even though her mom delivered and practically raised them. But mostly she’s mad about Stack ghosting her when he left for Chicago. Now she lives somewhere else, passing as white, but her mother’s dad was half Black, and she’s more comfortable here. I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who looked up if that was really Steinfeld’s heritage (it is) and also learned that her uncle is Jake “Body By Jake” Steinfeld (HOME SWEET HOME). That part of her background the character doesn’t share as far as we know.

Smoke goes to see his wife Annie (Wunmi Mosaku, HIS HOUSE) and the grave of their baby whose death may have caused the rift in their relationship. Annie is a Hoodoo practitioner and root healer, which he doesn’t so much believe in, and a hell of a cook, which he definitely does believe in, and that’s why he recruits her.

Most importantly they need music. Their ace in the hole is their younger cousin Sammie “Preacher Boy” Moore (introducing up and coming R&B singer Miles Caton), a blues prodigy rebelling against his reverend father (Saul Williams, co-director of NEPTUNE FROST) by playing that devil music to the drunks and fornicators. One of those is Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo, MORE AMERICAN GRAFFITI, superb as always), who they find playing harmonica at the train station and convince to risk his regular Saturday gig to be their piano player. And Sammie gets Pearline (Jayme Lawson, HOW TO BLOW UP A PIPELINE) to show up and sing despite/because he flirts with her knowing she’s married.

It’s no secret by now that this is a movie largely about the power of music. Coogler admits that he had the juke joint idea before he settled on which monster would show up. I’ve read that they wanted to make sure it wasn’t a musical, but to me it almost is, and the two obvious stand out scenes are a pairing of musical performances, one inside the juke and one outside. The first is very obviously the heart and highlight of the movie, a scene that gave me goosebumps and a gigantic smile and that everybody I’ve talked to about SINNERS immediately brought up before I told them it goes without saying which scene they liked best. I don’t want to diminish it with a description other than to say that it brilliantly visualizes the beauty and power of live music. (See the spoiler zone at the end of the review for a little more.)

In the context of the story there is a mythical, supernatural power on display here, but it’s beautiful because it’s such a perfect metaphor for something we’ve all experienced from music that moves our souls or our feet. SINNERS got me thinking about transcendent moments I’ve experienced watching live music. One that came to mind, because it had the feeling of reaching across time, involved The Roots at The Showbox, in I believe early 2007 because it wasn’t too long after James Brown died and they did an incredible medley of his songs mixed with classics by Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, etc. that sampled them. Another one was George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic at the Showbox SoDo (different place), maybe around 2010. I’ve seen them I’d guess dozens of times, so when I realized I would have to miss either the encore or the last bus I almost left. But they played a cover of “Let the Good Times Roll,” which was not even a song I thought I liked or anything, but the floor had thinned out, there was more room to move and those of us left, we just let loose. In my bones or my muscle memory or somewhere I was just feeling it, it seemed like I understood that song and its era more than I ever thought I would, and fuck it, it’s not that far, I didn’t mind walking home.

I don’t literally believe in griots who pierce the veil between life and death but I mean, I saw Prince once, I saw James Brown twice, Stevie Wonder twice. And we’ve all heard their records. The power is there if you’re open to it.

If you make a movie about “music is amazing” though your music better be pretty amazing. Luckily this is another meticulous and inventive score from Ludwig Göransson, who went to USC with Coogler, first worked with him on his 2011 student film Fig, and has since created all-timer themes for CREED and The Mandalorian and won Oscars for BLACK PANTHER and OPPENHEIMER. Unsurprisingly for a movie all about music he goes all out/all in (and was also executive producer). Reading about it I’ve learned about him studying with ethnomusicologists and blues experts, playing Sammie’s 1932 Dobro Cyclops resonator on the score, teaching Coogler to play guitar to help him with the writing, working with the actors to learn their instruments, that’s all interesting. But just from listening you hear how he layers a blues-guitar-based score with orchestral elements, and then other historical styles that come up, like the Irish folk music of the vampires, and as the movie and the night go on and things get out of hand, the score goes rock operatic. I don’t know if it’s the specific reference he’d point to, but I thought of Keith Emerson’s score for INFERNO and Goblin’s for TENEBRAE when the choir and organ and electric guitars crashed the party.

The vampire threat begins with one guy, a centuries old Irishman named Remmick (Jack O’Connell, 300: RISE OF AN EMPIRE), who smoke-trails into town right before sundown, chased by a Choctaw patrol led by Chayton (Nathaniel Arcand, GINGER SNAPS BACK: THE BEGINNING, PATHFINDER, COLD PURSUIT) and finds shelter with a gullible white couple, Joan (Lola Kirke, GEMINI) and Bert (Peter Dreimanis of the band July Talk). Those hunter guys are cool, I’d watch a whole movie about them, but they do their due diligence trying to warn these two of the danger and then get fuck out of the movie before dark.

Attracted by Sammie’s song, the trio shows up at The Juke. These vampires need to be invited in, but luckily the bouncer and then the twins don’t want the potential for trouble these unknown white people represent during Jim Crow. Now, I’ve only seen the movie once so far and I’ve read many reviews with interpretations that don’t necessarily match up with mine, but here’s what I think is unique about these villains. In a Black horror movie made at this time, set in this period, you assume that white vampires represent racists. When they act shocked to be excluded for the color of their skin and say they believe in equality, you assume that it’s a put on, they’re fucking around with their prey. And in a vampire movie of any era when the monsters sing corny songs and talk about “fellowship and love” and “saving” people you assume that they’re mocking Christianity.

That’s how it plays at first. But in the end I believed they were sincere. Maybe they’re not Christians exactly, and they’re certainly painted as metaphorical devils, but I think Remmick really doesn’t care for the KKK and I don’t think he stands in opposition to Christ like traditional vampires. Holy water is mentioned as a weapon, but we don’t see it used, crosses don’t seem to repel them, Remmick even joins in The Lord’s Prayer with a victim. The way I see it, these guys are serious, they want to share their version of eternal life, they’re holy rollers with teeth. We know that when one character gets her wish to be staked before turning and a vampire cries out her name in grief. They could’ve been together forever.

That’s how it plays at first. But in the end I believed they were sincere. Maybe they’re not Christians exactly, and they’re certainly painted as metaphorical devils, but I think Remmick really doesn’t care for the KKK and I don’t think he stands in opposition to Christ like traditional vampires. Holy water is mentioned as a weapon, but we don’t see it used, crosses don’t seem to repel them, Remmick even joins in The Lord’s Prayer with a victim. The way I see it, these guys are serious, they want to share their version of eternal life, they’re holy rollers with teeth. We know that when one character gets her wish to be staked before turning and a vampire cries out her name in grief. They could’ve been together forever.

It’s always fun in vampire movies to see how they’ll deal with the rules. Annie thinks they’re haints at first but explains that vampires are different because they’re taken over but retain their souls, stuck forever in this miserable life in the dark. She prescribes garlic, wooden stakes and silver and we get a fast montage where everybody gets their weapons ready. It does turn into a siege movie like FROM DUSK TILL DAWN, with some good violence, though I’ll admit that I was sitting a little too close to follow the chaos when it switched to full IMAX.

Mary is such an interesting character, wanting to (and ultimately being) accepted as family by this community, invited in (SPOILER, unless you’ve seen any advertising) both before and after she’s a vampire. It’s such a bummer that she ends up infiltrating The Juke for the vampires – passing as human, really – because to me it seems like she belongs there, she’s earned her place, but her inclusion ends up being the community’s downfall. Ironically though it’s a type of happy ending for her – she had been in a cursed life, told she could never be safe with her community or the man she loves. Now she ends up with him in other eras when it’s legal.

Annie’s spirituality completely transforms the normally tired vampire or zombie movie cliche of making a loved one promise to kill you before you turn. Here it’s not “don’t let me turn into one of those things,” it’s her religious belief that she will be reunited with “the ancestors” and with her baby, which does happen.

The theme I’ve seen discussed the most in reviews is cultural appropriation, the white vampires wanting so badly to get into this space for Black people, and then starting to turn some of them and share their memories. It could be a GET OUT situation of wanting to steal Blackness for themselves, or a form of assimilation. Many seem to see the scenes like the one where Remmick sings and dances to “Rocky Road to Dublin” with his growing vampire horde as a cultural takeover – we’ve stolen your people and now they’re out here with us dancing to our music. For example, in his excellent Hollywood Reporter piece, Richard Newby references “Remmick’s insistence on creating a single culture, absorbing the uniqueness of the Black American and Chinese American experience, until it is indistinguishable from white culture.” And Adam Nayman, in his review for The Ringer says that “their group performances intensify into a grotesque parody of homogenized (and deracinated) musical styles.”

But on my one viewing so far I think I read it a little different. I saw it more like a reflection of what’s going on inside. Despite their comically corny folk rendition of the blues song “Pick Poor Robin Clean” earlier, we see now that they can move a crowd, and is there not a connection between these traditions of music? Murder ballads of European origin turning into American folk and bluegrass and at least co-existing with the blues? I know Lead Belly got “In the Pines” from a guy who recorded traditional English folk songs, for example. And I felt the freshly turned Mary and Cornbread were bringing their own cultural histories to the dance floor, the undead equivalent of the spirits in the earlier scene. Was I wrong about that? I have listened to the soundtrack so I can confirm that by the end Göransson lays in a soul singer going to church on that song.

I see the argument for co-option but it doesn’t feel to me like pure vampire evil. Is this not a huge improvement over the earlier song? It definitely is when they reprise “Pick Poor Robin Clean” while surrounding the building with a growing multi-racial chorus. And I think I’ve now talked myself into understanding Franklin Leonard’s offhand comments about the movie being about Hollywood. Adding diversity to the production brings some authenticity, but Remmick is still in charge. So maybe it’s not comparable to Coogler making a movie whose heart beats to the rhythm of compositions by Ludwig Göransson, the son of a Swedish blues guitarist, raised on Metallica, invited in to study the blues in Memphis for this movie, to have their stories and their songs.

As I worked on this review I realized maybe my interpretation was influenced by having heard Coogler’s (highly recommended) interview on WTF where he says that “the categorization of different types of music is essentially like a form of segregation.”

When Marc Maron says “The main vampire, he’s appropriating the souls of Black people,” Coogler says, “Yeah, in a way, but also, they also appropriating him… there’s also a scene where they singing his music.”

“Well, half of it comes from there.”

“Exactly. Blues came from the continent of Africa,” Coogler says, “but what we recognize as Delta blues and American blues there was contributions from the Choctaw, contributions from the Irish community… all of these people had a thing in common, that they had been stepped on and made to feel less than.”

In interviews on MSN and IGN Coogler talks about his love for Irish music and for the character of Remmick. He describes Remmick’s style of dancing as “an act of rebellion. In the form of it, the stiffness of it that we come to know, it’s because it wasn’t allowed. For this character to come find his way to Clarksdale in 1932, who does he identify with? Where does he want to spend Saturday night?“

On NPR’s Fresh Air, when interviewer Tonya Mosley quotes Remmick’s line “I want your stories, and I want your songs,” Coogler says, “You got to finish it though. He says something after that. He says, ‘and you’re going to have mine.’”

So I think his view of the vampires’ point-of-view is more sympathetic or complicated than what seems to be the common reading, but he would also be the first to say that it’s only his interpretation. He also says that he “was not being conscious of” the metaphors in the movie. “I was trying to communicate a feeling through cinematic language. And the reality is, as I’ve gotten older in this business and in this craft, you know, I realized that if I can make something true, it’s up to the viewer to draw those parallels.”

So I will. In Smoke and Stack I don’t think we have opposites initially, but in the end (END SPOILER) they are because one is with his love in the afterlife and one has eternal life on earth with his. In a way the real protagonist, the guy we begin and end the story with, is Sammie. He’s the one who has to choose between his father’s preaching and his passion for music, and also between the two paths of his cousins. There’s obviously a nod here to the legend of a bluesman (most often Robert Johnson, though the story was originally about Tommy Johnson, no relation) who met the Devil at a crossroads and traded his soul for guitar skills. In this story Sammie turns the devil down, still has the skills, still decides to spend his life “dancing with the devil” in the sense of playing the blues. I don’t even know if that makes him one of the sinners or not, but I think he made the right calls.

I feel like I’ve gone on too long and also completely skipped over a whole bunch of subjects worthy of discussion – the sexuality, Lindo’s performance, the character of Grace and one of her choices, how beautiful it looks, the cool thing that happens at the end, the other cool thing that happens at the end, and much more. But I’m sure I’ll come back to it. SINNERS is a special one.

P.S.

SUPER SPOILER ZONE DO NOT READ UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES

Okay this really wouldn’t be considered a spoiler to most people, I just don’t want to give too much forewarning about the best part of the movie. If you’ve seen it you know the scene and in fact the moment when you realize Sammie’s performance is conjuring up not only visions/spirits of the past but also the future, confirmed by a guy playing an electric guitar wearing a very P-Funk-esque costume. I’ve seen a few people refer to him as “the afrofuturist guitarist,” but I have no idea what they call him in the credits, if they do, because I can’t find him. In the moment I assumed he was somebody, a known guitarist who’s really playing on the song or who we would be excited to see if we knew who he was, because that would absolutely work in this scene. But now it seems he’s not anybody specific, just a visual cue that someone from at least 40 years into the future has joined the party. I’m happy that the concept of the funk is represented in the movie. I know I’m not this lucky but it would be my dream for Coogler to direct the inevitable George Clinton biopic some day.

SUPER SPOILER ZONE PART II: THE RECKONING

Is it just me or did Hailee Steinfeld look exactly like Debi Mazar in that credits scene?

April 25th, 2025 at 11:32 am

I asked (in a random comment on a different review, and obviously after Vern had already seen this one, but hey) and man have you delivered, Vern. A beautiful review of the best movie I’ve seen in quite a while.

I teach Fruitvale Station in my first-year writing class and so watched it twice this semester alone, and I think it’s an incredibly successful debut for Coogler and early acting gem from Jordan. But to my mind this is the best film either/both have been part of, and gets better and better the more I think about it.

Thanks for helping me continue doing that!

Ben