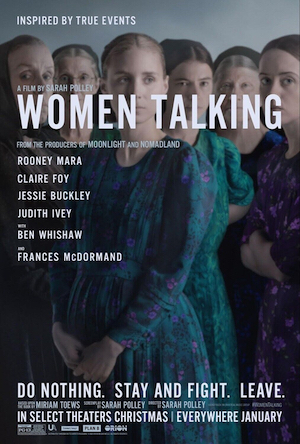

WOMEN TALKING is the new best picture nominated film from writer/director Sarah Polley, who is minor-key beloved as an actress for people around my age (THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN, GO, EXISTENZ, DAWN OF THE DEAD, SPLICE), but these days is more known as an acclaimed filmmaker (she directed AWAY FROM HER, TAKE THIS WALTZ and STORIES WE TELL). Now I’ve finally seen one of the ones she directed, and it lives up to her reputation. It’s based on a novel, but I would’ve guessed it was based on a play, because it’s one of those stories with a really concise but heavy-duty set up to put a top shelf ensemble of actors into a limited location (in this case a hay loft) with much to discuss, debate, and decide. Kind of a 12 ANGRY MEN deal, except there’s very intentionally only one man with a speaking part in the whole movie. And he’s way more sad than angry.

WOMEN TALKING is the new best picture nominated film from writer/director Sarah Polley, who is minor-key beloved as an actress for people around my age (THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN, GO, EXISTENZ, DAWN OF THE DEAD, SPLICE), but these days is more known as an acclaimed filmmaker (she directed AWAY FROM HER, TAKE THIS WALTZ and STORIES WE TELL). Now I’ve finally seen one of the ones she directed, and it lives up to her reputation. It’s based on a novel, but I would’ve guessed it was based on a play, because it’s one of those stories with a really concise but heavy-duty set up to put a top shelf ensemble of actors into a limited location (in this case a hay loft) with much to discuss, debate, and decide. Kind of a 12 ANGRY MEN deal, except there’s very intentionally only one man with a speaking part in the whole movie. And he’s way more sad than angry.

Canadian author Miriam Toews wrote the novel as a “reaction through fiction” to a real thing that happened in a Mennonite colony in Bolivia. So bear with me – this is awful. In an isolated religious colony (here seemingly in the U.S.) women and even young girls have, for some time, been waking up bruised and covered in blood as they have been repeatedly knocked unconscious by cow tranquilizer and then raped. For years they’ve been told by the elders that they imagined it or it was the Devil or a ghost or a punishment from God or all that kind of bullshit. But before the movie begins our young narrator Autje (Kate Hallett) and her friend Neitje (Liv McNeil) caught one of them running away, they got him to name the others, they were arrested and taken to jail. The men of the colony have gone to the city to bail them out, and given the women 48 hours to forgive them, or they will be excommunicated. Can you believe that shit?

So the women take a vote. Three options: do nothing, stay and fight, leave. It’s a tie between ‘stay and fight’ and ‘leave,’ so nine women have been elected to go into this loft and decide what to do. But time is running out before the men get back.

From the trailer and her past I assumed Frances McDormand (DARKMAN) was gonna be the powerhouse of the movie. She produced it, but her part – impossibly stern-faced, literally scarred – is practically a cameo. She voted ‘do nothing’ and puts in a good word for it with the ladies before immediately storming out of the meeting, unwilling to even consider other approaches. Refusing to put on the THEY LIVE glasses.

From the trailer and her past I assumed Frances McDormand (DARKMAN) was gonna be the powerhouse of the movie. She produced it, but her part – impossibly stern-faced, literally scarred – is practically a cameo. She voted ‘do nothing’ and puts in a good word for it with the ladies before immediately storming out of the meeting, unwilling to even consider other approaches. Refusing to put on the THEY LIVE glasses.

As in any debate, the angry voices tend to dominate. Salome (Claire Foy, FIRST MAN) is the one who tried to attack one of the rapists with a scythe. (The men moved them from a barn to jail for their safety.) She’s quite vehement about wanting to stay and fight these motherfuckers; you would be too if you just made a two day journey on foot to get antibiotics for your four-year-old daughter’s infection from being assaulted. Mariche (Jessie Buckley, JUDY) is furious on the other side because they’ve all been taught that forgiving is a requirement for entering their “Kingdom of Heaven” so she believes that anything other than giving in will doom them all.

But Mariche’s mother Greta (Sheila McCarthy, DIE HARD 2) sometimes takes control of the proceedings like a very good school teacher, pastor or support group leader. She first assures that they’re here to discuss either staying and fighting or leaving, so “We will not do nothing.” Then she says she wants to tell a story about her horses, Cheryl and Ruth. (Cheryl and Ruth come up several times in this movie. I like Cheryl and Ruth.)

The other dominant figure is Ona (Rooney Mara, “Classroom Girl #1,” URBAN LEGENDS: BLOODY MARY) – starry eyed, quasi-hippie poetical philosopher type, also pregnant with the child of one of her rapists. She seems spacey, impossibly kind, I like her but also understand why Mariche rolls her eyes with such disdain for sharing some fact about butterflies. When somebody calls Ona a dreamer, Agata (Judith Ivey, FLAGS OF OUR FATHERS) says that women in this colony have nothing but their dreams. I bet they don’t get to say that out loud too often.

Mejal (Michelle McLeod, “Skating Attendant,” MY SPY) appears to be older than Autje and Nietje and accepted at the grown ups table, but she represents the fiery youth perspective. She also wants to stay and fight, and has a dark sense of humor about it all. The meeting sometimes shifts into bitter gallows humor and laughter, which the two youngest seem a little put off by, but they themselves have been able to get bored, climb around the loft and play, despite what they’ve been through, and the uncertainty ahead.

The aforementioned token male is August (Ben Wishaw, Julie Taymor’s THE TEMPEST), a timid, thoughtful school teacher (who I must admit has a bit of a Simple Jack vibe) whose family was previously excommunicated, but he’s returned recently, maintaining his boyhood crush on Ona, and invited by her to take minutes for the meeting, since none of them can read or write. Ona seems to love him back, at least in some way, but she doesn’t believe in marriage, says that participating in it would make her not herself, not the person he loves. (This seems to be sincere and not an excuse. She’s a weirdo and that’s why he loves her.)

The women have to discuss what it means to fight, or what specifically they would fight for. Also what it means to leave – there’s much disagreement about under what circumstances, if any, they can bring their male children with them. And how do they know where they’re going? They have little concept of the outside world. Whichever of these paths they choose, they are deciding on a new life, an attempt at reimagining their world. This, in itself, is bold.

It’s maybe too obvious to state that it’s a hell of a cast, doing solid work. Surprisingly it wasn’t until after the movie that it occurred to me that Mara was David Fincher’s GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO and Foy was THE GIRL IN THE SPIDER’S WEB. It’s not as if the ensemble is lacking, but all movies could be improved by adding Noomi Rapace, and in this case that would’ve meant all three Lisbeth Salanders in one movie! Some day it’ll happen, I hope.

A title at the beginning calls WOMEN TALKING “an act of female imagination,” which comes from the book, and repurposes a phrase that was used to discredit the survivors in the Bolivian colony. Polley told PBS that “The film is told in the realm of a fable. So there’s something of an allegory about it. There’s something surreal and a heightened reality.” The conversations are stylized in a theatrical sort of way. It took me a bit to get used to the young narrator describing what she’s been through with a wisdom and artistry that initially struck me as beyond her years. But once I got into the movie’s groove I found it very powerful. The characters are better than most of us would be at expressing and weighing conflicting ideas on the spot, yet they don’t just come across as vehicles for the points that need to be made. They’re very human. They convey more personality than we’re accustomed to for characters who ride buggies.

The subtle thing I found most powerful about the movie is that in this temporary woman-led space they’re already doing things differently from how we do things here. They are in good faith trying to respect the opinions of women ranging from their teens to their seventies. Although they argue and get heated they also make a point of comforting and hugging each other when they get upset, and making genuine apologies when they realize they’ve been out of line. And they don’t treat it as shameful or uncomfortable when emotions are expressed, including a man crying. It’s a discussion with the goal of coming to an understanding, rather than of winning the argument.

There’s also a subplot about a transgender member of the colony (August Winter, “Child in Hold,” THE FOG remake) who stopped ever talking to the adults after being assaulted, and a strong connection is made by the simple act of finally calling him his chosen name of Melvin instead of his previous one. I imagine life for a trans person in this world would be much more difficult than what we see in the movie, but since Polley sees it as a fable she concisely illustrates what a no-brainer it should be for even an old lady raised in this community to get over her shit and respect a person’s wishes. You don’t have to fully understand a person’s life to know you oughta be polite to them.

In keeping with their belief in forgiveness, these talking women are overall accepting of minutes-taker August as a male ally – the term “not all men” is used unironically in reference to him. They also discuss philosophically that the men they fear and even the ones they were attacked by are also victims of the system. But it’s August’s job to stay behind to try to teach the boys to be better.

This is a movie about women escaping male violence and finding a better way. It doesn’t need to be about more than that, but it can be. The story also applies to any number of problems we’ve come to accept as permanent – gun violence, police violence, homelessness, etc. In the movie we see that fight or leave are not simple solutions, and the real ones will be even more complicated. But to ever see meaningful change we might need to take that brave leap of leaving – of agreeing that the status quo simply cannot and will not continue, and it’s time to build a better system from the ground up. Unfortunately that seems to scare most people more than living like this forever, so I fear we’ll be too cowardly and stupid to ever do it in my life time. WOMEN TALKING reminds me not to give up.

spoilerish postscript: These characters are living like electricity hasn’t been invented yet, so for a while it left me wondering what time period it was meant to take place in. I thought it was a great moment when the census guy drove by blaring “Daydream Believer” and I thought, “oh, okay, it’s the sixties” and then he announced he was doing the 2010 census. Real time warp there. I still haven’t seen Shyamalan’s THE VILLAGE but I guess seeing this kinda counts.

February 1st, 2023 at 3:18 pm

I read about the real-life case that inspired this (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manitoba_Colony,_Bolivia) and it struck me as odd that the book/movie is about the perpetrators getting away scot-free, while in the real world, they were turned over to the police, got sentences of a quarter-century each, and reportedly can’t return to the Mennonite colony for fear of lynching. Seemed to me the truth was awful enough without having to add in some Death Wish bit about how their scumbag lawyers get them off and they laugh their way out of the courtroom.