A couple months ago I got on a Jean-Michel Basquiat kick. You probly know who that is, but if not, he was a New York City graffiti artist in the early hip hop era, transferred his skills to paintings for galleries, became rich and famous and friends with Andy Warhol and stuff in a brief, prolific life before (like so many bright lights) dying of a drug overdose at 27.

A couple months ago I got on a Jean-Michel Basquiat kick. You probly know who that is, but if not, he was a New York City graffiti artist in the early hip hop era, transferred his skills to paintings for galleries, became rich and famous and friends with Andy Warhol and stuff in a brief, prolific life before (like so many bright lights) dying of a drug overdose at 27.

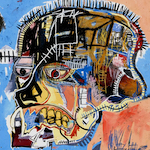

Set aside the inspirational underdog story, the meteoric rise, the quirky details, the tragic ending. All interesting, but you don’t need any context for his art to be incredible. Labelled a “neo-expressionist,” he just has this lively, messy style, an explosion of scratches and scrapes and colors and doodles and words. If they are child-like, then the child in question must’ve remained young for 100 years, evolving his drawing into highly sophisticated crudeness. There are traces of influences from cartoons to African art, he sometimes references boxers and current events and social issues, but he translates it into these distinctive scribbles and cryptic/poetic phrases, sculpting beauty and humor from garbage and decay and vandalism. I don’t know of anybody quite like him, and lately (even before… you know) I’ve really been feeling it’s important to honor and glorify the true originals and pure artists among us, through my chosen medium of, uh, movie reviews. So here I am, glorifying Jean-Michel Basquiat.

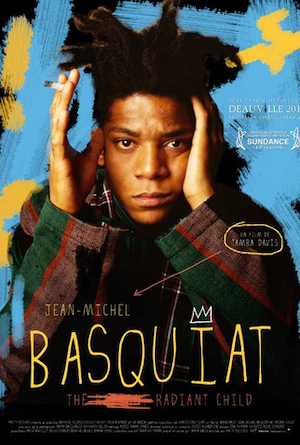

First I watched the documentary JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: THE RADIANT CHILD, directed by Tamra Davis. Yes, that’s the lady who did CB4, BILLY MADISON and HALF BAKED, but we learn from the movie that she befriended Basquiat when she was an employee of an L.A. gallery. In 1986 she and her friend Becky Johnston (who later wrote UNDER THE CHERRY MOON, THE PRINCE OF TIDES, SEVEN YEARS IN TIBET and HOUSE OF GUCCI) taped an interview with him in a Beverly Hills hotel room. When he died she put the footage away, too heartbroken to do anything with it until 2010, when she decided to thread it through this story of her friend’s life and career, told with existing footage and new interviews of Julian Schnabel, Fab 5 Freddy, Thurston Moore and all kinds of people.

First I watched the documentary JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: THE RADIANT CHILD, directed by Tamra Davis. Yes, that’s the lady who did CB4, BILLY MADISON and HALF BAKED, but we learn from the movie that she befriended Basquiat when she was an employee of an L.A. gallery. In 1986 she and her friend Becky Johnston (who later wrote UNDER THE CHERRY MOON, THE PRINCE OF TIDES, SEVEN YEARS IN TIBET and HOUSE OF GUCCI) taped an interview with him in a Beverly Hills hotel room. When he died she put the footage away, too heartbroken to do anything with it until 2010, when she decided to thread it through this story of her friend’s life and career, told with existing footage and new interviews of Julian Schnabel, Fab 5 Freddy, Thurston Moore and all kinds of people.

Arguably the most important interview is not a famous person, but Suzanne Mallouk, a longtime girlfriend of Basquiat’s who lived with him as he was coming up and is clearly the basis of a fictional character in the biopic BASQUIAT. I was glad I watched this first. You get the sense he could be a pain in the ass as a person, latching onto girlfriends to pay his rent just like the rich collectors who would later become his benefactors. But they couldn’t help but love him.

One complaint in reviews of the documentary is that there’s no time to consider the paintings – you see so many of them in quick cuts. Yeah, true, but also it just creates such a potent impression of an explosive imagination and talent. It multiplies the power of his art by the medium of film. We see volumes upon volumes of his work, intercut with memories of New York at the time, the downtown scene he was involved in, the legends he ran with, from Madonna to William S. Burroughs. A barrage of his creations and experiences working together in aggregate to create a larger feeling.

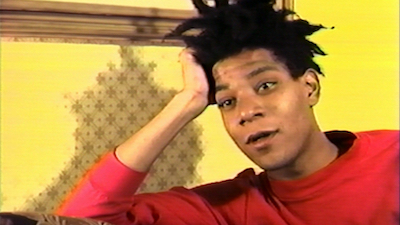

Also you just get so much real footage of him – from the public access show TV Party where he first came out as the graffiti artist SAMO©, to in his studio painting, to TV interviews, to that hotel room, that it’s like you get to hang out with him while you’re hearing all these stories from the people who loved him. It just makes him seem like such a sweet, unique person even outside of what he created. They tell us at the beginning that he became “famous for being famous,” but I came out thinking he was famous for being himself.

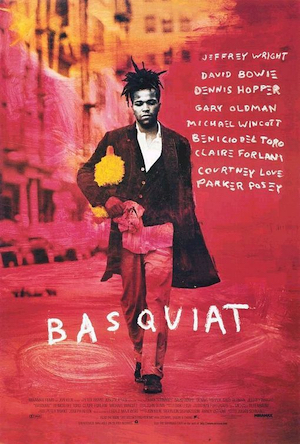

BASQUIAT (1996) is the directorial debut of the painter Julian Schnabel, who has since directed acclaimed films including BEFORE NIGHT FALLS and THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY. It’s not your name brand biopic, exactly, but it begins with the ol’ flashback/origin story/dream opening – he’s a kid, and his mother (Hope Clarke, BEAT STREET) brings him to see The Guernica. She’s so moved she cries, then turns to him and sees a glowing crown on his head – predicting his future with the image that became his trademark.

BASQUIAT (1996) is the directorial debut of the painter Julian Schnabel, who has since directed acclaimed films including BEFORE NIGHT FALLS and THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY. It’s not your name brand biopic, exactly, but it begins with the ol’ flashback/origin story/dream opening – he’s a kid, and his mother (Hope Clarke, BEAT STREET) brings him to see The Guernica. She’s so moved she cries, then turns to him and sees a glowing crown on his head – predicting his future with the image that became his trademark.

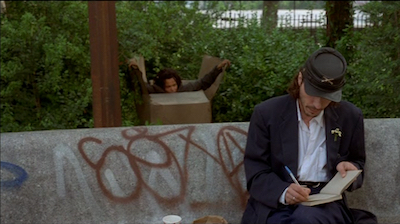

Grown up Jean-Michel wakes up smiling from this mixture of biographical anecdote and fantasy. We can’t see at first, but he’s not in a bed – he’s in an upright cardboard box in some bushes behind a bench where influential Artforum critic René Ricard (Michael Wincott, following THE CROW, DEAD MAN, STRANGE DAYS and PANTHER), is sitting. His words serve as narration as he writes in a notebook, completely oblivious to his future discovery emerging from a box looking like a silent movie comedian.

Grown up Jean-Michel wakes up smiling from this mixture of biographical anecdote and fantasy. We can’t see at first, but he’s not in a bed – he’s in an upright cardboard box in some bushes behind a bench where influential Artforum critic René Ricard (Michael Wincott, following THE CROW, DEAD MAN, STRANGE DAYS and PANTHER), is sitting. His words serve as narration as he writes in a notebook, completely oblivious to his future discovery emerging from a box looking like a silent movie comedian.

BASQUIAT was the first time I noticed Jeffrey Wright, and it’s weird that now he’s such a solid character actor type that he plays Jim Gordon in THE BATMAN, because I used to think of him as a chameleon. There was this, and Peoples Hernandez in SHAFT (2000), and MLK in BOYCOTT. Here he clearly studied Basquiat’s odd rhythms, gestures and postures in the interviews, and makes a character out of them. I think this depiction might be a little more off-putting than the real guy, but he’s still a likable eccentric.

Well, depending on your tolerance level. A waitress named Gina (Claire Forlani, POLICE ACADEMY: MISSION TO MOSCOW) seems charmed by him even though he gets kicked out for pouring syrup on his table, wiping it with the menu and drawing her face in it. We have the benefit of knowing he’s an actual genius, but everybody at that diner has a right to hate his ass. He invites her to see his band at The Mudd Club. It’s unclear what exactly he’s doing in the band so nobody reacts when he just leaves the stage to hang out with her.

Well, depending on your tolerance level. A waitress named Gina (Claire Forlani, POLICE ACADEMY: MISSION TO MOSCOW) seems charmed by him even though he gets kicked out for pouring syrup on his table, wiping it with the menu and drawing her face in it. We have the benefit of knowing he’s an actual genius, but everybody at that diner has a right to hate his ass. He invites her to see his band at The Mudd Club. It’s unclear what exactly he’s doing in the band so nobody reacts when he just leaves the stage to hang out with her.

There’s obviously alot of fictionalizing and compositing here, but with many scenes based on the stuff you hear about in the documentary, like the time he followed Andy Warhol (David Bowie, LABYRINTH) into a restaurant and got him to buy a postcard. Despite such greatest-hits moments, it feels like an oddball ’90s indie movie, with Wright’s Basquiat hazily stumbling through encounters with an ensemble of cool actors, like Dennis Hopper, Parker Posey, Paul Bartel and Tatum O’Neal as art world people. Benicio Del Toro (white hot from THE USUAL SUSPECTS) plays Benny, his best friend in the pre-fame days. Going from the documentary this composite character seems mostly based on SAMO© graffiti collaborator Al Diaz, but I wondered if his experimental video art could mean he was also inspired by Kevin Bray, a music video director and close friend who later travelled to Africa with Basquiat and was supposed to go to a Run DMC concert with him the night he died. That might just be wishful thinking on my part because it’s funny to imagine this weirdo Benicio character going on to direct ALL ABOUT THE BENJAMINS and the remake of WALKING TALL.

Another ambiguous character is Courtney Love as a woman Jean-Michel hits on on the sidewalk and cheats on Gina with. He calls her “Big Pink,” and I thought she might be an off brand Madonna, except there’s another scene where it’s mentioned that he dated Madonna. There’s also a weird friend in goggles who visits him once that I considered being Rammellzee (the genius artist and rapper whose 12” single “Beat Bop” Basquiat famously produced, released and drew the cover for) or Lee Quiñones (graffiti artist star of WILD STYLE), but for some reason he calls him Jean-Claude Killy (and I gave up on finding him in the credits).

Another ambiguous character is Courtney Love as a woman Jean-Michel hits on on the sidewalk and cheats on Gina with. He calls her “Big Pink,” and I thought she might be an off brand Madonna, except there’s another scene where it’s mentioned that he dated Madonna. There’s also a weird friend in goggles who visits him once that I considered being Rammellzee (the genius artist and rapper whose 12” single “Beat Bop” Basquiat famously produced, released and drew the cover for) or Lee Quiñones (graffiti artist star of WILD STYLE), but for some reason he calls him Jean-Claude Killy (and I gave up on finding him in the credits).

Willem Dafoe is in one scene playing an electrician Jean-Michel works with in an art gallery. In RADIANT CHILD, Suzanne Mallouk says she agreed to support him after he worked one shift with an electrician and couldn’t handle it. I’m not sure what I think about that. On one hand, that poor lady had to have had her own stuff she’d rather have been doing, he should’ve paid his fair share, and also I think it’s generally good for people to work and meet people and sometimes be humbled a little and etc. At the same time I think it would be a better world if everyone could just do art instead of a job they don’t like, and I’m glad that Basquiat in particular didn’t waste his limited years punching a clock. So thank you for your sacrifices, Ms. Mallouk.

While not working he has time to write strange poems on walls, draw on old things he finds lying around, put a pile of tires in his apartment and paint them white. The kinds of things people make fun of as fake art but mostly when he does it it’s kind of awesome. On the other hand there’s the scene where Gina wakes up and discovers that he painted over her paintings. He tries to explain that it’s because “I couldn’t look at them anymore, they’re kind of impersonal,” but believe it or not that does not win her over. In the movie, at least, he’s not a good boyfriend.

He finally meets Rene after delivering a painting to a drug dealer (Rockets Redglare) during a party. Rene chases him down and tells him he’ll make him a star. He puts on a show with dirty old doors and windows hung next to his canvases – they look really cool – and that’s where he meets Annina Nosei (Elina Löwensohn from AFTER BLUE and SHE IS CONANN), who agrees to give him a place to paint so he can do a show with her. This was when he really exploded, and the movie is big on depicting these various patrons of the arts (critics, curators, collectors) fighting over Jean-Michel, trying to claim him for themselves. There’s a really uncomfortable part where he’s supposed to meet René and some people at a restaurant after his big show but Warhol and a bunch of rich collectors (and Vincent Gallo as himself) wave him to their table. René follows and makes a big scene until he gets kicked out.

Since it’s directed by Schnabel, both a friend of Basquiat and a famous painter in his own right, I assume he knows what he’s talking about. He’s represented in the movie as a fictional character named Albert Milo (Gary Oldman in nice guy mode), with Schnabel’s actual family playing Milo’s, and he put himself at that table with the assholes who tear Jean-Michel away from the friends who were with him before he was famous. That’s an interesting self-critique, but mostly his avatar seems like a good guy with a genuine love and respect for his fellow artist.

Their lives are very different. We knew Jean-Michel when he was homeless; Milo has a huge place and happy family, few apparent concerns other than artistic purity. There are a handful of allusions to the challenges of being a Black man in general (unable to get a cab) and in the art world in particular (an exaggerated version of a real interview Basquiat found racially condescending; in the movie the interviewer is Christopher Walken). He also bristles at all the white people assuming he’s still poor. He borrows $3,000 from Andy Warhol to buy all the caviar at a deli because Michael Badalucco was rude to him, and pays the tab for a table full of white businessmen who gave him a dirty look.

He wants to be accepted, but not by forgetting where he came from. His mother was Puerto Rican, born in Brooklyn; his father (played here by Leonard Jackson, BASKET CASE 2) was from Haiti. There’s a scene where his limo driver Shenge gushes over the chance to meet him, which surprises him. The character is based on Basquiat’s Trinidadian assistant and fellow artist Shenge Ka Pharaoh, but he’s played by Haitian-American Jean-Claude La Marre, now the prolific filmmaker behind the PASTOR JONES and CHOCOLATE CITY franchises.

So Schnabel definitely tries to dig into cultural identity a little, but obviously his strength is in his understanding of studios and galleries and collectors. Though he depicts Basquiat before those days, he doesn’t see him as a hip hop figure. There is no Fab 5 Freddy character, no Rammellzee. Schnabel opens the film with “Fairy Tale of New York,” ends with Leonard Cohen’s version of “Hallelujah,” has another Pogues song and three Tom Waitses in between – the hat trick of heartbreaking white man gutter balladeers. But it works. It’s Schnabel’s view of his friend.

For a movie about an artist by an artist, maybe it’s a little too literal. Occasionally Jean-Michel sees surfing footage in the sky, but we see his eyes darting around much more than we see the world through them. Maybe Schnabel had too much respect for his friend’s unique perspective to try to simulate it. It must’ve been hard enough just re-creating the paintings. But it’s an admirable attempt.

I’ve been meaning to rewatch BASQUIAT for a while. I definitely thought about it when AMERICAN FICTION came out, and when I saw HOLD THE DARK. But as ridiculous as it may sound, it was the new LL Cool J album The F.O.R.C.E. that finally got me to do it. It’s actually a really good album (produced by Q-Tip) and the funkiest song on it is called “Basquiat Energy.”

The song has an admittedly superficial take on the meaning of Basquiat. LL’s mostly bragging about getting women and having gold chains, the best lines being stuff like “Wrote my name on the wall, now it’s up in lights” and “We from the bottom, baby, now we up on Mount Olympus.” He talks about going quickly from recording in Rick Rubin’s dorm room to “wearing upscale threads fully paid in advance,” pretty standard-issue rags to riches shit, drawing a parallel between himself and Basquiat, who lived in the same city he did, intersected with some of the same people, and quickly catapulted from homeless graffiti writer to rich and famous painter.

What strikes me about it is that in all material ways LL has surpassed Basquiat. When he recorded Radio not one person conceived of there ever being a rapper as famous as he would become by the time of Walking With a Panther. Then he had many years as a movie and TV star, invested well, owns all kinds of businesses and shit, could hardly be more successful. Yet it was important to him to come back and make a late career record aimed at re-proving himself to serious hip hop fans. So I think he’s using “Basquiat energy” as an aspirational term not for material success, but true artistic greatness, vision, originality. I find that refreshing.

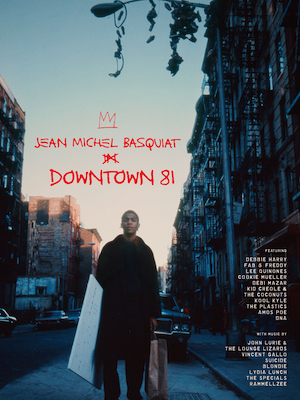

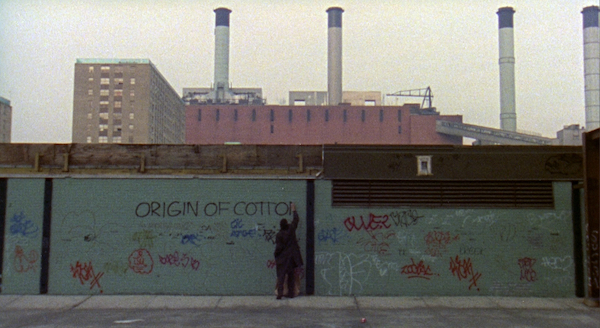

To really see Basquiat’s vision, look at his work, not his life story. But to see where it came from, the soil it grew out of, check out DOWNTOWN 81, a less coherent movie than BASQUIAT, but an important artifact from a fascinating time I wasn’t around and a place I’ve never been. My Roman Empire, I guess. Filmed in 1980 and 1981 to showcase Manhattan’s post-punk music scene, it stars the real Jean-Michel Basquiat when he was only known in the neighborhood for his graffiti. It was directed by Swiss photographer Edo Bertoglio, but it was the brain child of writer/producer Glenn O’Brien, author of the first national magazine article to mention Basquiat (a High Times profile of the graffiti scene) and host of the aforementioned TV Party. The movie ran out of funding in the ‘80s and was left unfinished until O’Brien got the rights back in 1999.

To really see Basquiat’s vision, look at his work, not his life story. But to see where it came from, the soil it grew out of, check out DOWNTOWN 81, a less coherent movie than BASQUIAT, but an important artifact from a fascinating time I wasn’t around and a place I’ve never been. My Roman Empire, I guess. Filmed in 1980 and 1981 to showcase Manhattan’s post-punk music scene, it stars the real Jean-Michel Basquiat when he was only known in the neighborhood for his graffiti. It was directed by Swiss photographer Edo Bertoglio, but it was the brain child of writer/producer Glenn O’Brien, author of the first national magazine article to mention Basquiat (a High Times profile of the graffiti scene) and host of the aforementioned TV Party. The movie ran out of funding in the ‘80s and was left unfinished until O’Brien got the rights back in 1999.

He still had the audio for the musical performances that are the meat of the movie, but not the dialogue, so Basquiat’s lines are dubbed by Saul Williams (NEPTUNE FROST). It was a good choice, especially since it’s mostly poetic voiceover narration.

He still had the audio for the musical performances that are the meat of the movie, but not the dialogue, so Basquiat’s lines are dubbed by Saul Williams (NEPTUNE FROST). It was a good choice, especially since it’s mostly poetic voiceover narration.

“I awoke. Had I been dreaming? I think so.” At the beginning he gets let out of a hospital, he’s told that he’s cured and free to go. “He said I was free. He was right, but he had no idea.”

At the front desk they hand him his personal items, including a clarinet, which he carries around for much of the movie. “You gotta blow your own horn in this town,” he says. A rich model named Beatrice (Anna Schroeder) notices him playing on the sidewalk, stops and offers him a ride in her convertible, asks “Why don’t you let me take care of you?” and becomes his patron. One of many things in this movie that reflected or predicted his actual life.

In the next scene he gets evicted from his apartment and spends most of the rest of the movie carrying around a painting he wants to sell for $500. He was just starting to paint on canvases, so this was one of his first. He was also homeless at the time, sleeping in the production offices. The movie itself was his Beatrice.

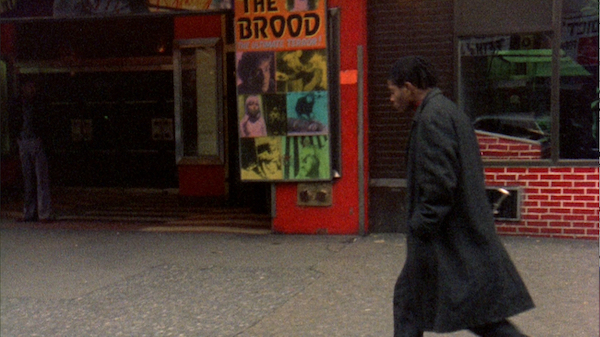

Hey, check this out. THE WARRIORS was playing when they filmed this.

Also THE BROOD.

Man, i love those old theater marquees and displays. I’m so glad they got this place on film.

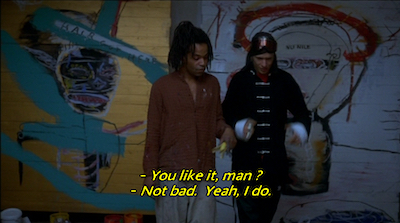

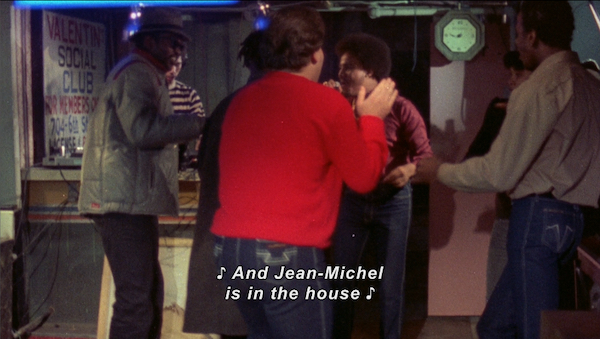

Unlike BASQUIAT, DOWNTOWN 81 has an interest in hip hop. One of the best parts for my interests is when he sees Fab 5 Freddy and Lee Quiñones working on a mural. Freddy invites him inside to see a rapper (Kool Kyle) and DJ (uncredited?), there are only a handful of people there, he puts his painting and bag down next to the DJ stand and shakes hands with the MC. Just a very intimate and casual daytime hip hop club experience.

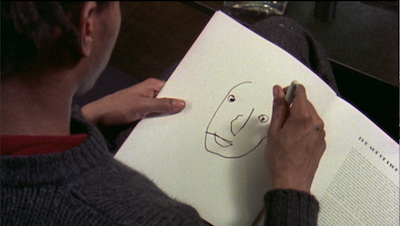

My other favorite part is when he has a Sharpie and he adds some random letters and doodles to someone’s Man Ray photography book. When he draws this face it’s striking because you can see the loose way he holds the pen to create that style. It makes a little more sense when you see him in action.

These somewhat aimless Basquiat vignettes are designed to string together performances by some of the post-punk type bands O’Brien had been writing about in his column in Interview magazine. They include Tuxedomoon, D.N.A., The Felons, The Plastics, James White & The Blacks, and Kid Creole & The Coconuts. I’d heard that name before, seen their records, but didn’t really know what they were – they seem like a fun show, and an interesting thing to pop up in the middle of all those other bands. Kind of campy, kind of retro, very serious about musicianship and showmanship.

I don’t know any of the other bands either, but it feels like time travel to see what they were up to. And there are peeks into their lives, like a tangent about this dude (Walter Steding) who records experimental music, plays shows, wants to do a painting. He complains about how much of a cut the club owners take, how they want to pay him less if he’s having fun, what the critics write about the show. He feels it’s hard work for minimal reward and wants to dedicate more time to his personal projects. He doesn’t foresee the future where nobody can afford to live in New York City and do that stuff, so he doesn’t know how good he has it.

There’s a subplot, if you can call it that, about Jean-Michel seeing somebody (apparently it’s Marshall Chess, producer of Electric Mud!) stealing a van full of his band’s equipment. He finds his bandmate tied up and it’s Michael Holman, who some of us know as the host and creator of the early hip hop TV show Graffiti Rock. Holman and Basquiat had a band together called Gray (named after Gray’s Anatomy, a book Basquiat was fascinated with since his mom gave it to him as a child). Vincent Gallo was also a sometime member (and is in the movie somewhere, not sure if I noticed him). Their song “Drum Mode” is on the soundtrack, but we sadly don’t see them performing.

There’s a subplot, if you can call it that, about Jean-Michel seeing somebody (apparently it’s Marshall Chess, producer of Electric Mud!) stealing a van full of his band’s equipment. He finds his bandmate tied up and it’s Michael Holman, who some of us know as the host and creator of the early hip hop TV show Graffiti Rock. Holman and Basquiat had a band together called Gray (named after Gray’s Anatomy, a book Basquiat was fascinated with since his mom gave it to him as a child). Vincent Gallo was also a sometime member (and is in the movie somewhere, not sure if I noticed him). Their song “Drum Mode” is on the soundtrack, but we sadly don’t see them performing.

To wrap this all up like a fairy tale, there’s a scene where a so-called bag lady asks Jean-Michel for a good night kiss, saying she’s a princess and will grant him a wish. He doesn’t believe her, but he’s a nice guy and up for an adventure, so he does it. I didn’t notice until her transformation into a Glenda the Good Witch/fairy godmother type that she’s Debbie Harry! After the movie she was the first person to buy one of Basquiat’s paintings (for only $200 though), and he played the DJ in the “Rapture” video when Grandmaster Flash couldn’t do it. Anyway, the princess grants his wish for a bunch of cash, he buys a used Eldorado, writes “GOLDWOOD” on the side (?) and drives out of town.

It’s funny to me that he wanted to get the hell out of there, because now DOWNTOWN 81 plays as such a love letter to that place and time, when all the coolest and most creative people gravitated to one area and fed off each other’s energy to create new styles of music, new styles of art, new ways to dress. You look at a movie like this and you see so many people who made their own mark before or after as a musician, a filmmaker, a photographer, an artist. Eszter Balint from STRANGER THAN PARADISE and Anne Carlisle from LIQUID SKY are in a fashion show scene, Cookie Mueller from the early John Waters movies is in a go-go dancing scene, director Amos Poe is seen in the Mudd Club (around the time of SUBWAY RIDERS, before ALPHABET CITY), John Lurie is in it. Others we don’t recognize, they just made a name for themselves in the city, to be appreciated for a while, remembered fondly by those who were there, luckily memorialized in time capsules like this, chronicles of a mythical era.

With cities today making it much harder to live cheaply, and with no magical fairy princesses to kiss good night, can a thing like that ever happen again? No, I doubt it. Not exactly. But humans find ways to adapt. That’s what Basquiat and his peers were doing, after all – turning abandoned warehouses into studios and apartments, walls into canvases, records into instruments. We have to figure out our own methods of using the things we have to conjure up what we’ve only imagined, to express what’s inside us, and make the outside more interesting. Or at least we should try. I don’t know what the hell else to do.

With cities today making it much harder to live cheaply, and with no magical fairy princesses to kiss good night, can a thing like that ever happen again? No, I doubt it. Not exactly. But humans find ways to adapt. That’s what Basquiat and his peers were doing, after all – turning abandoned warehouses into studios and apartments, walls into canvases, records into instruments. We have to figure out our own methods of using the things we have to conjure up what we’ve only imagined, to express what’s inside us, and make the outside more interesting. Or at least we should try. I don’t know what the hell else to do.

November 14th, 2024 at 2:54 pm

I can’t help but think that, after all these years, we’re in danger of movies and art like this, a movie about a legendary artist made by another legendary artist, becoming just nothing to no one, forgotten by older generations who could not keep the torch for the new ones. It’s important to keep that light strong, so thank you, Vern. Great review (I’ve never seen Downtown 81!) and a great sentiment — these people lived, they were important, and they are responsible for some of the culture we still have left. Always, always, keep the flame.