If you were going to build the prototype for the ultimate man, wouldn’t it pretty much be 1974 Muhammad Ali? He’s a badass, a fighter with style. I don’t even really like boxing that much but I love to watch him dance around, swinging his fists so fast. Even Bruce Lee liked to watch him.

If you were going to build the prototype for the ultimate man, wouldn’t it pretty much be 1974 Muhammad Ali? He’s a badass, a fighter with style. I don’t even really like boxing that much but I love to watch him dance around, swinging his fists so fast. Even Bruce Lee liked to watch him.

He’s handsome in a manly way. He’s charming, eloquent, and funny as hell. His humor is mostly based around making preposterous boasts… but it’s not some Danny McBride overconfidence thing, because he usually delivers. In this movie there’s an interview where he goes into detail about high speed photography and how one of his punches was proven to take only four one hundredths of a second, like a blink or a camera flash, and all this is setup for him to claim “Now, the minute I hit Sonny Liston, all of those people blinked at that moment, that’s why they didn’t see the punch.” A tall tale, but based on a true, provable incident.

Of equal importance, Ali has integrity of the Stickin It To The Man variety. He didn’t believe in the war so he refused to sign up for selective service, knowing it would endanger his career, reputation and freedom, and he held his head high the whole time. And he was outspoken about racism too. And he was right.

Also, it turns out, he has good taste in music. He loves soul music. (In this movie he seems to make fun of Johnny Cash a little bit, but I’m gonna forgive him.)

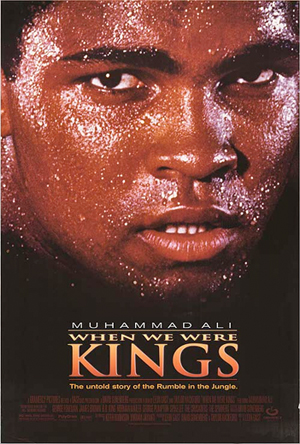

Even in Zaire, where his famous Rumble in the Jungle fight against George Foreman took place that year, Ali was like a super hero. This is the story of that fight and the Zaire 74 three-day music festival, “Bigger than Evel Kneivel and the Kentucky Derby on the same day,” according to Ali. It’s illustrated with beautiful footage directed by Leon Gast (HELLS ANGELS FOREVER) and shot by a gang of great documentarians. I noticed Albert Maysles on the credits as one of five cinematographers, after he’d already directed SALESMAN and GIMME SHELTER. Also Maryse Alberti, who shot CRUMB, THE WRESTLER and will shoot CREED. And Roderick Young, who shot WATTSTAX.

Even in Zaire, where his famous Rumble in the Jungle fight against George Foreman took place that year, Ali was like a super hero. This is the story of that fight and the Zaire 74 three-day music festival, “Bigger than Evel Kneivel and the Kentucky Derby on the same day,” according to Ali. It’s illustrated with beautiful footage directed by Leon Gast (HELLS ANGELS FOREVER) and shot by a gang of great documentarians. I noticed Albert Maysles on the credits as one of five cinematographers, after he’d already directed SALESMAN and GIMME SHELTER. Also Maryse Alberti, who shot CRUMB, THE WRESTLER and will shoot CREED. And Roderick Young, who shot WATTSTAX.

The story is then explained through 1996 interviews, mostly Norman Mailer and George Plympton, who were there covering the story, and Ali’s biographer Thomas Hauser. You also got a little Spike Lee, so that it’s not all white guys. You know, Taylor Hackford is credited as co-director, so he must’ve done the contemporary part of the movie, which means we could’ve had Helen Mirren in there I guess.

The best interviews are Ali on dirt roads and in hotel rooms, in dirty sweats or sharp polyester shirts, shadowboxing and taunting. Aesthetically I prefer the direct cinema, no interviews, drop-you-right-into-the-experience approach of SOUL POWER, the companion piece about the music festival that they made with leftover footage in 2008. Watch that one to see more James Brown, Bill Withers, B.B. King, the Spinners, The Crusaders, etc. But for this one the more traditional documentary approach works because they edit together alot of historic footage and explain Ali and Foreman’s careers before and after Zaire as well as the specifics of what happened in the fight. Things that benefit from expert testimony.

Other than a corny new ballad and a Fugees/Tribe Called Quest/Busta song at the end it’s scored by music from the festival, so it maintains a powerful sense of the time and place. The imagery is incredible, the swagger of these great athletes, the sweaty performances of the musicians, juxtaposed against the African setting. There are great montages, like the one set to the J.B.’s “Funky Good Time” cutting between the performance, soldiers marching, merchants carrying their wears on their heads in baskets. And you just see the Americans coming alive with black pride. One scene has Ali thrilled to be in the cockpit of a plane with a black pilot and crew. Like he never thought of this before.

Ali says “It’s the first assembly in the history of all America where all the topnotch blacks of America and the people of Africa had something together all on a world level, we are all meeting each other and learning more about each other. It’s the first assembly among the American black men and Africans I guess in the history of the world, and it’s a big honor to be part of that too. Plus I gotta whip George!”

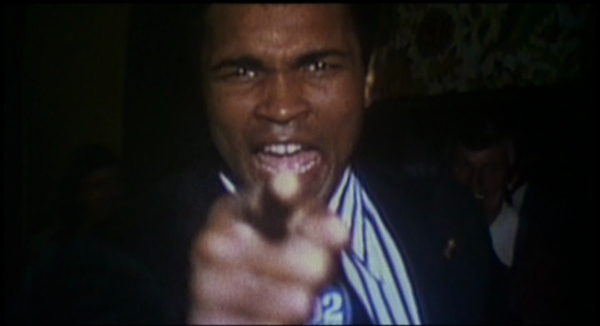

It’s got alot of great dramatic themes going on at once. Of course there’s the underdog story of Ali making a big show out of a fight all the sports writers and commentators think he can’t win. There’s a great clip of him taunting Howard Cosell for saying “very honestly I don’t think he can beat George Foreman.” Ali angrily points his finger and yells into the camera like a wrestling interview.

He makes several points and then at the end he says “I’ma let everybody know that thing you got on your head is phony, and it comes from the tail of a pony!”

And exactly as he finishes saying it he’s already darting off camera.

Remember to do that instead of the popular “mic drop” thing, people. Mics are fragile and expensive.

Then there’s the visionaries-making-impossible-dreams-come-true aspect of the whole event. The festival organizer and all the struggles he went through are only briefly shown here, you see more of that in SOUL POWER. But we see how Don King – described by Hauser as “quite a remarkable man… one of the brightest people I’ve ever met… one of the most charismatic people I’ve ever met… one of the hardest working people I’ve ever met… also totally amoral. I can’t think of another man who has done more to demoralize fighters, exploit from fighters, and ruin fighters’ careers” – came virtually out of nowhere and built his career by putting together this momentous event.

And there’s all kinds of suspense and drama within. Foreman cuts himself above the eye during training, causing a delay so all of them have to stay in Africa for 6 more weeks. Ali almost calls it off. While they stay we see how the people of Zaire rally around Ali, and Foreman can’t understand why. He’s darker skinned, why don’t they relate to him more? Well, because they don’t know who he is, and they already love Ali. Sure, they were both great fighters, but Ali was legendary because he also stood up to the government, to the white man. “For us he was defending the good cause for Africans and the whole world” says interviewee Malik Bowens, an actor who later played President Mobutu Sese Seko in ALI, perhaps based on the strength of his work in DOUBLE TEAM.

Meanwhile, Foreman represented America to them, in a bad way. They assumed he was gonna be a white guy, that he showed up and was black didn’t deter them from disliking him. He arrived with his German shepherd, which reminded them of the police dogs the Belgians used against them, so they’re like “Who is this motherfucker?” Plus it is possible that they objected to this outfit:

But probly not, it’s pretty cool I guess. I’m sure Rudy Ray Moore would wear that too, so I’ll allow it.

It’s all beautifully put together. Even the rare cheesy part, like the photo montage near the end, is fun to watch, because you get to see photos of Ali with Malcolm X, Elvis, the Beatles, the Jackson 5. One minor complaint: they cut to a weird Miriam Makeba performance as Plympton is telling some story about a succubus. She’s got crazy eyes and is doing a weird breathy thing as part of the song, but let’s not imply through editing that she’s some kind of witch or monster there to curse George Foreman. Oh well.

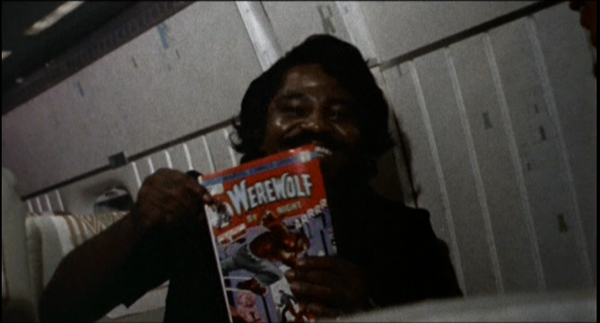

There are all kinds of great little moments. I like the interview with Ali’s mom, because after a minute I realized how much she looked and sounded like him. And I like the still photo that captures Plympton’s mouth agape at the moment that Foreman is falling to the mat. Equally historic, the footage that captures the Godfather of Soul enthusiastically endorsing the Marvel comic book Werewolf By Night.

But it’s the bigger picture that makes this movie feel so powerful: the celebration of greatness in sports and music as entertainment and inspiration for the downtrodden of America and Africa. Ali talks about the ol’ “knowledge of self” and not asking white people for anything, and they give an epic example of this by putting this whole thing on with primarily black participants, organizers and financiers.

I think the meaning of the title is twofold for African-Americans. Don King says “We left Africa in shackles and feathers and chains, you know? And we’re coming back in an aura of splendor and scintillating glory. The champions are here. So we’re trying to get the champions of the sports world, champions of the music world. So we put ’em both together and we got one champion that’s so intermingled and intertwined and we’re fused into one entity.”

(“The brother said something there!” raves James Brown.)

In other words it’s looking back to before slavery – when we were in Africa, when we were the ones in charge, when we were kings and queens – but also it’s looking back from 1996 to 1974, to that time when these black men and women flew to the Motherland as a representation of American black culture, and they were welcomed as heroes, as legends, as kings. Less so for Foreman, I guess. Ali had kids running after him and crowds chanting “Ali bomaye” (kill ‘im) like they’re his army.

But all this plays out against a background of turmoil. The beautiful opening credits intercut a Crusaders drum solo with black and white footage of Ali interviews, scuffles between Africans and white colonialists, and the KKK back in the states. And the fight is funded and overseen by Zaire’s Mobutu, who Mailer says “looks the archetype, the epitome of a closet sadist, the sorta guy if you meet him at a bar you think ‘Oh my god, who are the poor women who are associated with this fella?'” He tells a legend about Mobutu allegedly rounding up and killing 100 criminals to terrorize the underworld into behaving while the world spotlight was on the country. He says the floor of the arena had been stained with blood.

I guess that’s life, huh? The most beautiful things intermingling with the most sickening, sometimes without knowing it. Hopefully more of the former can lift us out of the latter.

The whole event is a miracle, and the movie is too.

January 19th, 2015 at 2:13 pm

This thing was so good it basically rendered Mann’s film redundant.