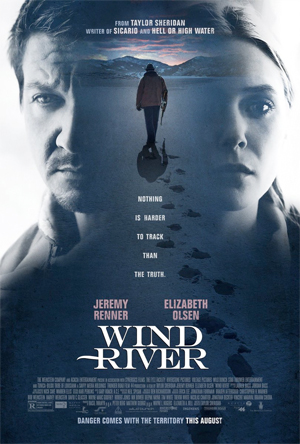

WIND RIVER, new on video this week, is a thriller written and directed by Taylor Sheridan, who’s on the radar now because he wrote SICARIO and HELL OR HIGH WATER. Jeremy Renner (Catwoman: The Game) plays Cory Lambert, a hunter for the Fish and Wildlife Service in Wyoming. When he drives out to the Wind River Indian Reservation to find what wild animal killed some livestock and spend some time with his son Casey (Teo Briones) he finds a dead woman in the snow. He knows her, her name is Natalie (Kelsey Asbille, THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN). She’s a good friend’s daughter. When they ask him to help show around FBI Agent Jane Banner (Elizabeth Olsen, OLDBOY) he ends up unofficially joining the investigation with her and tribal sheriff Ben (Graham Greene, DIE HARD WITH A VENGEANCE).

WIND RIVER, new on video this week, is a thriller written and directed by Taylor Sheridan, who’s on the radar now because he wrote SICARIO and HELL OR HIGH WATER. Jeremy Renner (Catwoman: The Game) plays Cory Lambert, a hunter for the Fish and Wildlife Service in Wyoming. When he drives out to the Wind River Indian Reservation to find what wild animal killed some livestock and spend some time with his son Casey (Teo Briones) he finds a dead woman in the snow. He knows her, her name is Natalie (Kelsey Asbille, THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN). She’s a good friend’s daughter. When they ask him to help show around FBI Agent Jane Banner (Elizabeth Olsen, OLDBOY) he ends up unofficially joining the investigation with her and tribal sheriff Ben (Graham Greene, DIE HARD WITH A VENGEANCE).

It’s a quiet, broody modern western type of a movie with matter-of-fact badassness in the dialogue and bursts of violence, tonally comparable to the aforementioned Sheridan joints, THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADAS ESTRADA, NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN, stuff like that. But unlike any of those the wide-open landscapes are covered in snow. It’s not sweaty, it’s frost-bitten.

There’s more going on here than is immediately stated. The reason Cory takes this so personally, why his ex-wife Wilma (Julia Jones, HELL RIDE, JONAH HEX) refuses to ever go back to the rez, why her parents have winter clothes to loan to Jane, why Cory looks at her the way he does when she puts them on, is that his daughter was killed too. In fact, Natalie was her best friend, who reported her missing. So he’s eager not only to share his grieving experience with her father Martin (Gil Birmingham, Jeff Bridges’ partner in HELL OR HIGH WATER, also he used to be a bodybuilder and played Conan the Barbarian at Universal Studios Hollywood), but to get the killer for him – something he was unable to do for himself.

There’s a macho paternalistic thing going on here. Protecting daughters, avenging daughters. A movie about missing Native American women, but helped largely by white people. And the man is the lead even though the woman is the FBI agent. I have friends who, although they agreed it was good, had a problem with it being a white people story or a man story. You may agree, and these things were definitely in the back of my mind, but I think there’s plenty to counteract them. It has what I think of as a novelistic structure where right as they’re on the verge of figuring out what happened it flashes back to show us what led up to it. And in this segment we finally meet Natalie and she’s so vividly full of life we feel like we knew her all along as a present tense person, not a past tense victim. And she seems so much more in control of the situation than we assumed, or than her brother (Martin Sensmeier, MAGNIFICENT SEVEN) said. Until she’s not.

There’s a macho paternalistic thing going on here. Protecting daughters, avenging daughters. A movie about missing Native American women, but helped largely by white people. And the man is the lead even though the woman is the FBI agent. I have friends who, although they agreed it was good, had a problem with it being a white people story or a man story. You may agree, and these things were definitely in the back of my mind, but I think there’s plenty to counteract them. It has what I think of as a novelistic structure where right as they’re on the verge of figuring out what happened it flashes back to show us what led up to it. And in this segment we finally meet Natalie and she’s so vividly full of life we feel like we knew her all along as a present tense person, not a past tense victim. And she seems so much more in control of the situation than we assumed, or than her brother (Martin Sensmeier, MAGNIFICENT SEVEN) said. Until she’s not.

I like how much it refuses to glamorize murder. The perpetrator is not only sick, but pathetic and cowardly. As they always say, rape is about power, and Cory makes a vivid closing argument to the face of the rapist about his weakness vs. Natalie’s status as a true “warrior.” I love his fascination with (SPOILER) Natalie running six miles in the snow barefoot, and Jane bringing it up later in the hospital. When she says it it’s with horror and sympathy. When he says it it’s with admiration.

Cory’s rugged-hunter-loner philosophizing about survival is my favorite part of the movie. He makes some good speeches and has some great tough guy dialogue. “I’m a hunter, Martin. What do you think I’m doin?”

https://youtu.be/wDex2vkuFhM

HELL OR HIGH WATER also dealt with the mistreatment of Native Americans and their existence in the modern world. This one is more direct about it, though the protagonist is still white. This time he’s down via marriage and fatherhood (like Seagal in THE PATRIOT). He’s portrayed as what they call now a “good ally,” because he tries to make his son proud of the Native side of his heritage and he speaks up for their historic struggles even when only among white people. He does get called out once for saying “we.” But the sadistic vengeance that he applies seems to be not only for Natalie, or Martin, or his daughter Rachel, but for all indigenous people who have been savaged by white people.

But it reminds me more of SICARIO. We have another female law enforcement agent who is nervous, seemingly over her head, pushed around and discounted, this time for being an outsider sent in unexpectedly, unprepared, unsure how things are done around here. But hell yeah she comes through. She proves herself tough as hell, just in more of a John McClane way than a Beatrix Kiddo. She can be physically overpowered by men, and that means she has to fight harder and longer to overcome them. But she can shoot, she can fearlessly yell down a mob of dudes all pointing guns at each other, she can manage a life-or-death situation with pepper spray in her eyes.

Though the age difference between them doesn’t seem vast, I think the wearing of his daughter’s clothes gives him an extra need to protect her, but all he really does is tend to her wounds afterwards. She survives in what Ben calls “the land of you’re on your own.”

You see a story like this, you expect it to tie together. When he figures out who killed Natalie, he’ll figure out who killed his own daughter, right? Nah, I don’t think so. Life’s not usually that simple. He’ll probly never know the answer to that, and he’d be the first to tell you it wouldn’t help that much. No – actually Wilma would be the first one. “You won’t get the answers you’re looking for, no matter what you find.” This is more about him living with the unknowable.

I like how the ending (YES, SPOILER) lightens all this horribleness a little bit by making us think it’s gonna get even worse and then cutting us some slack. Early in the movie that are hints that Martin could be suicidal, so when Cory returns to his house and can’t find him, we get a couple minutes of fearing the worst. It’s such a relief to find out that not only is Martin alive, but that he was saved from an unexpected place – a call from his fuck-up son, who probly wouldn’t have done so without Cory’s intervention. A little bit of hope, a little bit of redemption, out there in the cold.

p.s.

I think there need to be more Native American stories told by Native American filmmakers, but is it fair to hold that against a movie that’s something else? I think people would be equally or more offended if this white guy Taylor Sheridan presumed to tell the story with all Native characters, and I don’t think asking him to ignore Natives in his movies because he’s white is the answer either.

That’s my feeling, but I don’t want to be the white guy pretending to have the final word on that, so I looked for reviews from Native American media sources. In doing so I learned that the film was 90% financed by a company called Acadia Entertainment that’s owned by the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe. They also produced LBJ!

Anyway, I found this very negative piece by Charles Kader on Indianz.com. He actually only mentions seeing a commercial for the movie, but I think we can be pretty sure he wouldn’t like the full movie either. (He does like KNIGHTRIDERS though!)

This review by Vincent Schilling of Indian Country Today is not as well written as the Kader piece, but is extremely favorable about the movie:

https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/culture/arts-entertainment/movie-review-taylor-sheridans-wind-river-gripping-realistic-beautifully-crafted/

Also this New York Times piece by Kevin Noble Maillard, “What’s So Hard About Casting Indian Actors in Indian Roles?”, is a thoughtful look at that topic.

November 15th, 2017 at 10:48 am

This worked best for me in the first half when it’s a genre thriller that takes on serious themes (like in the old Walter Hill style, or PRISONERS), but then I think it makes a mistake of trying to be a message-movie foremost. It has a good sense of location, anyway.

I had the same concerns about it being a white saviour narrative. I’d never say it shouldn’t be allowed to take this route; I just wonder about the rationale of also making the secondary lead a white character. I personally would be less bothered if Taylor Sheridan told it as an indigenous story (so long as he did his research), but who gets to tell Native narratives is a very hot topic debate, especially here in Canada, and I’m also a white dude, so I don’t claim to know what’s the best approach. I just see a movie like this, and am like, “Ok, THAT’s how you wanted to tell this story?”