Something about this gloomy post-election mood has got me digging out my jazz CDs and records. Actually, it started with the handful of blues albums I own, which makes perfect sense, you can see how Orange Dawn (as I’ve decided to call our new age) would make me feel like listening to “Hell Hound On My Trail.” After that I went to Nuclear War by Sun Ra. Obvious through line there as well. But eventually I moved on to one of the Thelonious Monk albums I’ve latched onto over the years, Underground.

Something about this gloomy post-election mood has got me digging out my jazz CDs and records. Actually, it started with the handful of blues albums I own, which makes perfect sense, you can see how Orange Dawn (as I’ve decided to call our new age) would make me feel like listening to “Hell Hound On My Trail.” After that I went to Nuclear War by Sun Ra. Obvious through line there as well. But eventually I moved on to one of the Thelonious Monk albums I’ve latched onto over the years, Underground.

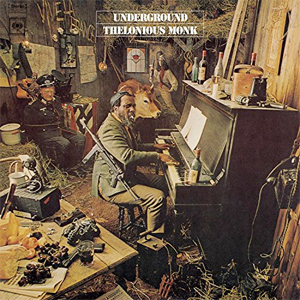

Check out the cover, with Monk hunkered down in a… barn? Bunker? Basement? with a rifle, some grenades, and a tied-up Nazi, makes it seem rebellious. He’s supposed to be part of the French Resistance, it seems. He looks like a jazz guerrilla committing musical sedition.

Check out the cover, with Monk hunkered down in a… barn? Bunker? Basement? with a rifle, some grenades, and a tied-up Nazi, makes it seem rebellious. He’s supposed to be part of the French Resistance, it seems. He looks like a jazz guerrilla committing musical sedition.

In general, though, the jazz I like feels more spiritual. It’s a mix of repetitive rhythms and unpredictable melody, spinning around, building momentum, plowing along until it explodes or stops and quietly steps away. Usually there are no words, no subjects. Just moods. Colors. So it’s like a meditation, a prayer in tongues.

All this meditating and praying and then the act of trying to put my love of piano into words to write about LA LA LAND inspired me to pull out the ol’ THELONIOUS MONK: STRAIGHT NO CHASER dvd. This is a beautiful, sad documentary about my favorite pianist. It’s produced by Clint Eastwood and Malpaso, who put up the money to finish the movie when nobody else would.

The credited director is Charlotte Zwerin, editor of Maysles Brothers films including SALESMAN and GIMME SHELTER. She put it together and gives a bit of Monk’s personal story through interviews with his son (discussing then-private information about Monk’s struggles with mental illness) and Pannonica de Koenigswarter, a rich cat lady friend he spent some of his later years with. When I watch this I worry at first that she’s a mistress. That would be really shitty because his wife Nellie seems so nice and puts up with so much, but I think it’s innocent. Koenigswarter was a baroness and scion of the Rothschilds who supported bebop musicians – Monk and Charlie Parker both died in her homes. And this is not mentioned, but she was actually part of the French Resistance that inspired that album cover. I bet he asked her about that.

In footage shot in the ’80s we see an unused piano that Koenigswarter bought for Monk and still has in her Weehawken, New Jersey home, next to a window with an amazing view of the New York skyline. It would be an amazing place to play music, I bet, except we know from other shots that it’s surrounded by dozens of cats. So it’s a beautiful image that I imagine smells like pee.

The majority of the movie comes from much older footage shot by documentarians Christian and Michael Blackwood for a German TV special. In lovely, grainful black and white 16mm we see 1968 Monk on stage, in the studio, traveling, sometimes being interviewed for a magazine, or with his wife at home. The back of the dvd quotes producer Bruce Ricker (director of EASTWOOD AFTER HOURS: LIVE AT CARNEGIE HALL, music consultant for THE BRIDGES OF MADISON COUNTY and MYSTIC RIVER) calling the footage “the Dead Sea Scrolls of jazz.”

It really is incredible stuff. It’s mostly music. We see him in clubs, sweaty forehead, restless. Sometimes he gets up, walks across the stage, or spins around (an odd habit we also see him doing in front of confused travelers in an airport). He’ll seem angry, or ready to leave. Then he’ll quickly sit down and immediately be in a groove.

You notice he has this habit of shuffling his right foot around while he plays. Not exactly tapping, not exactly sliding. And then the camera person notices too and zooms in on it.

One of the clubs you never see the crowd, but they sound small. Another one, when he was starting to get more popular, they look like this:

It’s getting crowded in there, but still pretty damn up-close-and-personal. It looks like he’s playing at Arnold’s Diner from Happy Days.

So you feel like you’re right there in this tiny club, hearing this incredible music that no one else could play, that not that many people appreciated until later, when it was way too late to witness something like this. The recording sessions are equally intimate.

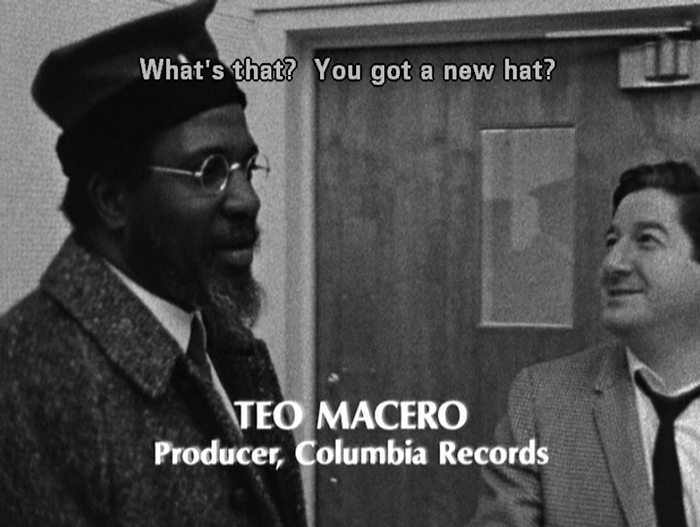

We see Monk happily greeting his fellow musicians and producer Teo Macero, and later we see him being testy or odd with them as the composing and recording processes go on. In one scene he keeps demanding Macero play back to him what they just rehearsed, not understanding that (in trying to follow his requests) they weren’t recording. But the documentarians were, so we could play it back if we wanted to. Here, Monk, let me rewind the dvd.

You also see him sitting at the piano with the sheet music for “Boo Boo’s Blues” (a song on the aforementioned Underground) written in pencil, the rest of the band going through asking him what each note is to make their own copies, him not knowing how to be very cooperative about it. You get the feeling it’s a huge pain in the ass to work with him, but they’re patient because it’s worth it.

I don’t know enough about music to explain Monk’s style, but I’ll give it a shot. To me it sounds just slightly askew. It’s not random, like free jazz, it’s pretty little songs, but the notes are all weird, like he wrote a catchy tune and then decided to play the notes in between the original notes, and found something greater.

Dave Chappelle tried to explain it in DAVE CHAPPELLE’S BLOCK PARTY. He says he taught himself “Round Midnight” to try to understand its weird timing, and apply it to his comedy.

And maybe there’s something a little deeper to why that original sound is so powerful. We hear through interviews about a time when musicians had to have a license in order to perform, and could have it taken away if they committed a crime. They used those laws to harass jazz artists in certain cities, so Monk liked to stay in New York. You know, with the coastal elites.

It’s weird, but this music that is now for old guys who like hats or Ryan Gosling, that Bleek Gilliam had to beg people to listen to a quarter century ago, that begat Kenny G’s “Songbird,” was at one time a threat to The Man. It seems throughout modern history there has always been a dangerous music that was gonna turn our kids into sex maniacs or devil worshipers. Alot of these cultural panics, and especially this particular one, are based in racism. But thank God the police were able to stop Monk from playing for a while because they found some pot on him! It doesn’t matter if both pot and jazz are legal now, I shudder to think how dangerous it would’ve been if more of it had been smoked and played back then. Close call on that one.

According to Monk’s “personal manager” Harry Colomby in the movie, Monk was an “underground figure” at this time, and his music was rebellious.

“Blacks who listened to that music saw an expression of independence and pride and strength. Thelonious Monk just represented that. The earliest example of a black revolution, a black uprising in a sense, was in music, was in the bebop period, where the musicians didn’t try to please an audience, but played their music their way. It was a real independent expression.”

This is a white guy saying this, a guy who went on to produce a bunch of Michael Keaton movies and write JOHNNY DANGEROUSLY. So I don’t know how well he can speak to that, but it’s an exciting concept to me. It’s hard to wrap my head around it now, the idea of a guy just playing an instrument in such a way that he’s a countercultural figure. I mean, Jimi did that, but he got to use words, and the National Anthem.

Even more than WHEN WE WERE KINGS, this might be the documentary I’ve rewatched the most times, because of the simple appeal of an interesting person and time documented within a whole bunch of great musical performances. It’s sad but not too heavy, and only 90 minutes long, man. I think you should try it out. I think you might like it.

January 5th, 2017 at 9:45 pm

Thanks Vern! I found lots of interesting stuff in this review. First of all, I am fascinated by the ground level reaction to the election of Trump and how it is manifesting in the day-to-day lives of those that voted against him. Politics in New Zealand seem so inconsequential (our Prime Minister just resigned last month and it didn’t seem like anyone really cared) and it is interesting to me to hear from people who are so invested in the political machinations of their country.

Secondly, Thelonious Monk is the only jazz I have listened to and kinda got. My wife is a pianist and there is a lot of piano music being played in our house, with Monk being her favourite non-classical, so she will be very keen to see this.

Thirdly, is music subversive anymore? The pop charts are filled with the most hypericum loses performers and songs, but for me there is nothing interesting about the actual music, so it garners little to no attention.