As I write this there’s a terrible sickness going around. All the world’s authoritarian assholes have agreed it’s time to whip out the ol’ “immigrants are scary” cliche to rile up the dumbest motherfuckers on earth. In my country there’s a specifically idiotic one where the two sweaty goblins running on the Keep Trump Unaccountable For His Crimes ticket purposely spread a racist myth about Haitian immigrants in a specific town in Ohio, leading to weeks of chaos, harassment and bomb threats. And of course they’ve refused to apologize, doubled down on the lies, and promised to deport these (legal!) immigrants if they manage to take power again.

As I write this there’s a terrible sickness going around. All the world’s authoritarian assholes have agreed it’s time to whip out the ol’ “immigrants are scary” cliche to rile up the dumbest motherfuckers on earth. In my country there’s a specifically idiotic one where the two sweaty goblins running on the Keep Trump Unaccountable For His Crimes ticket purposely spread a racist myth about Haitian immigrants in a specific town in Ohio, leading to weeks of chaos, harassment and bomb threats. And of course they’ve refused to apologize, doubled down on the lies, and promised to deport these (legal!) immigrants if they manage to take power again.

What can I do about this within my chosen medium of outlaw film criticism? The level of ignorance and gullibility a person would have to possess in order to believe these particular grifters on this specific con seems almost unfathomable, and I do not think it’s within my gifts as a writer to express the humanity of Haitians to somebody lacking the wisdom of the common housefly. All I can do is enlighten myself a little by watching a movie from Haiti and trying to learn a little something. There aren’t many of them available in the U.S., but I found a pretty good one.

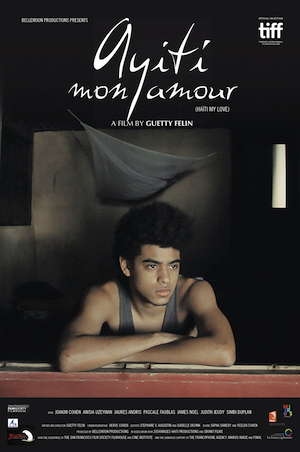

AYITI MON AMOUR (Haiti my love) is from 2016, it played the Toronto International Film Festival and it was Haiti’s first entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars (though it wasn’t nominated). It’s a low-on-plot, high-on-poetry, magical realist portrait of a few people who live near each other in a little fishing village. It basically weaves together three stories, loosely connected. One is about a writer who hears a woman’s voice talking to him – she’s the fictional person he’s writing about, she gives him ideas but also asks him questions about herself and walks around trying to understand her character. Another story is about a fisherman whose wife Odessa is very sick, he takes care of her as she talks about “going home.” Also he talks to a cow about it. The other, most interesting one is about a teenager named Orphee who’s lonely and unhappy, and for a while becomes charged with electricity. All of them are drawn to the sea.

AYITI MON AMOUR (Haiti my love) is from 2016, it played the Toronto International Film Festival and it was Haiti’s first entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars (though it wasn’t nominated). It’s a low-on-plot, high-on-poetry, magical realist portrait of a few people who live near each other in a little fishing village. It basically weaves together three stories, loosely connected. One is about a writer who hears a woman’s voice talking to him – she’s the fictional person he’s writing about, she gives him ideas but also asks him questions about herself and walks around trying to understand her character. Another story is about a fisherman whose wife Odessa is very sick, he takes care of her as she talks about “going home.” Also he talks to a cow about it. The other, most interesting one is about a teenager named Orphee who’s lonely and unhappy, and for a while becomes charged with electricity. All of them are drawn to the sea.

Orphee is the character we get to know best. His dad, who died in the earthquake, was half French, so he’s light-skinned and the kids at school are mean to him and call him “white roach.” He seems to have spent time in France and the U.S. and would like to go back. He also speaks some Japanese, but mostly just to annoy his mom, he says. He has a dog he loves and a lush backyard with a sandy beach right past the fence. Look at this!

His temporary super powers happen after he’s in the water and a large fish tail moves past him, but I couldn’t tell if it was supposed to be a mermaid or something. His mom tries to make him keep to himself, but the locals all line up to touch his arm as a way to charge their cell phones, radios and laptops. Then he uses the electricity to try to heal or soothe Odessa, if I understand correctly.

Later he’s walking on the beach at night, the fictional lady is playing banjo by candlelight in her backyard, recognizes him as “the school teacher’s son,” and asks him to buy her menthols and rum. They drink together, dance to imaginary music, and (it’s implied) more than that. This seemed very familiar and then I realized it was because it was reminding me of the craziest thing that happens in Matty Rich’s THE INKWELL. That movie is way too obscure to assume it was an influence, but they’re weirdly similar, except instead of just becoming a man this kid also loses his electricity powers.

The cinematic style is very loose, with natural lighting and lots of scenes from real life. We see the characters at a march commemorating the victims of the earthquake, at a student protest, when boats coming in unloading goods. There are scenes that seem like they just let non-actors have a real conversation, like where a group of fishermen discuss not being able to catch as many fish as they used to, how people fish carelessly and the law doesn’t stop them so they’ve ruined the sea.

When it’s not those racist lies I talked about at the beginning, I think the image we see of Haiti in America is mostly disaster and poverty. AYITI MON AMOUR mentions Hurricane Flora, an ongoing drought, the 2010 earthquake, and the difficulty to completely recover from these things. But those they’re hovering in the background, it’s mostly not a movie about struggle, but about people living their lives, experiencing joy and beauty, so it gives a very different impression of life in Haiti than we’re used to. Yeah, it seems like a simple lifestyle with more limited use of electronics than ours, but not entirely. The fisherman gets annoyed by a call on his cell phone while he’s out in his canoe.

What struck me most is how beautiful the place is – almost a paradise. True, there are lots of weathered and wrecked buildings, rusty doors, simple homes, dirt roads, motorcycles instead of cars. But everyone lives along the beach, they dress nice, some even enjoy artistic pursuits. Orphee’s home looks like a vacation resort, but at one point his mom makes some comment about the rich and white people who live on the water, so she definitely considers herself middle class or lower.

One thing I always like when watching movies from a culture I’m totally ignorant about is seeing references to American things, a reminder of how much the world is connected. I noticed a couple here. There’s a guy wearing a BRIDESMAIDS promotional tee, another with an NBA All-Stars shirt. And Orphee remembers a time when his dad shaved his head and it made him look like E.T. I think it makes sense that E.T. would be the one to bring together all the nationalities. I love that guy.

On the other hand, they’re hearing a few bad things about us in the media. Someone reads from a newspaper, “In the United States, someone is killed by a bullet every five minutes. And this year, the prison population has increased by 25 percent.” Sounds accurate, unfortunately, but I’d hate people to judge me for being from this country. Hmm.

I read afterward that most of the cast are locals, but Joakim Cohen, who plays Orphee, is the director’s son. Jaures Andris, who plays the fisherman, really is a fisherman. The only two members of the cast who are professional actors are the writer and the muse, but they’re also known for other artistic endeavors. James Noel is a famous poet and Anisia Uzeyman is the Rwandan actress who co-directed NEPTUNE FROST. Oh shit, I know that movie! In fact I own it on blu-ray. Small world.

Don’t worry, I’m not gonna pretend to understand Haiti now because I saw one movie. But at least it’s one additional impression. I wish I could also see something more commercial, but I’m not sure if there is such a thing, because there just isn’t that big of a local industry. As the Wikipedia entry for “Cinema of Haiti” currently puts it, “Oppressive dictators and economic struggles have limited production.” But there is documentary footage shot in Haiti going back to the early days of cinema, and movie theaters have existed there since 1907. In the ‘60s they watched Italian and French films, but during the Duvalier dictatorship there was strict censorship to hide revolutionary ideas. Still, imported westerns and martial arts films were popular, and in AYITI MON AMOUR there’s a line about Friday being “Kung Fu Night” wherever Orphee is headed to watch movies. Unfortunately there doesn’t yet seem to be a tradition of Haitian-made genre films – I could find information about a few dramas and romances, but that’s about it. It doesn’t help that the tyrannical Duvaliers caused such poverty that in the 28 years of their reign only four Haitian films were produced, one of them a short. Since the fall of the regime there has been a tradition of activist film including by directors Arnold Antonin (whose documentaries include HAÏTI LE CHEMIN DE LA LIBERTÉ) and the more internationally known Raoul Peck (who did that James Baldwin documentary I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO and the biopics LUMUMBA and THE YOUNG KARL MARX).

Most Haitian cinema is foreign financed. This one is executive produced by Mira Nair, and CCH Pounder is one of the associate producers, but it was actually crowdfunded through Indiegogo. Director Guetty Felin had done a post-earthquake documentary called BROKEN STONES, but this one made her the first Haitian-born woman to direct a narrative feature entirely in Haiti. In this interview posted on Medium by a New Zealand writer called @devt, the director describes her film as “a fiction about life after disaster, kind of like what Rossellini did with PAISA on the heels of fascism,” and says “I just wanted to put Haiti in conversation with the outside world on her own terms. I wanted Haiti to steer the conversation for once.” But she also says “I don’t know why I make the films I make, they just come to me and do not leave me alone until I make them.” Kind of like the woman in the movie, though she eventually gets bored waiting for the writer and goes off on her own.

Asked about Orphee speaking Japanese, Felin says “It was my own subtle way of connecting our experience to that of Japan that suffered a huge tsunami just 13 months after our earthquake,” also mentioning the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and “how Japanese film directors crafted beauty and poetry out of cruelty and restored the dignity of their people.” As she says, cinema “can eliminate our boundaries.” I think right now we need cinema more than ever.

September 30th, 2024 at 11:09 am

You have a way with words when it comes to dressing down the shitbrained fast-fascist chucklefucks that are ruining the world for the rest of us and also for themselves. Thanks for taking the time to spotlight a film like this that we may not have discovered otherwise.