See, this is why I continue being a best picture completist – it gets me to watch some good movies I was planning to skip. This year when they announced the ten nominees I had already seen six of them and was planning to see another three. ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT is the only one I’d had no desire to see. In fact I’d been hoping it wouldn’t get nominated, and felt a little resentment that according to my self-imposed rules I was gonna have to watch it.

See, this is why I continue being a best picture completist – it gets me to watch some good movies I was planning to skip. This year when they announced the ten nominees I had already seen six of them and was planning to see another three. ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT is the only one I’d had no desire to see. In fact I’d been hoping it wouldn’t get nominated, and felt a little resentment that according to my self-imposed rules I was gonna have to watch it.

I have no familiarity with the 1929 novel by Erich Maria Ramarque, the 1930 film version by Lewis Milestone, or the 1979 tv version, so my skepticism was not about being a purist. I just had heard an impassioned argument that it’s a movie with cool battle scenes that turn a powerful anti-war story into some SAVING PRIVATE RYAN shit about heroism and sacrifice. And that didn’t sound like something I wanted to see.

But I did see it, and I’m glad, because I honestly can’t even contemplate how anybody would think even one moment of this movie was about heroic sacrifice. I thought it was a brilliant cinematic illustration of the sheer pointlessness of war. This is not just war is hell. This is war is savage, inhuman, purposeless, madness. A sickness that men with their pride and egos and inadequacies inflict on themselves, on others, on the earth, and once they get the ball rolling it’s easier to keep pushing it then try to stop it.

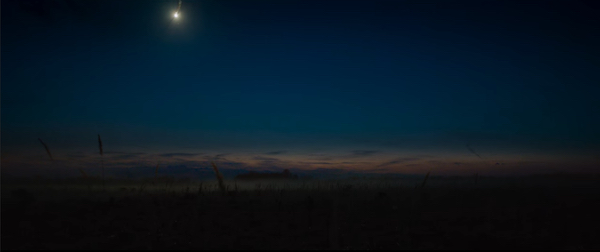

It begins, like the title says, with quiet. There are occasional hints of THE THIN RED LINE here in images of nature minding its own business in the middle of a combat zone. A mother fox is in her den, feeding her cubs. On a nearby field the fog clears to reveal the leftovers of a battle – motionless bodies splayed everywhere, covered in morning frost. The tableau starts to be peppered here and there with spots of black powder and smoke as (stray?) bullets and shells fly in from the distance, even though from the looks of it there hasn’t been a living soul on this field for hours.

It begins, like the title says, with quiet. There are occasional hints of THE THIN RED LINE here in images of nature minding its own business in the middle of a combat zone. A mother fox is in her den, feeding her cubs. On a nearby field the fog clears to reveal the leftovers of a battle – motionless bodies splayed everywhere, covered in morning frost. The tableau starts to be peppered here and there with spots of black powder and smoke as (stray?) bullets and shells fly in from the distance, even though from the looks of it there hasn’t been a living soul on this field for hours.

When we jump back to the battle itself there’s nothing remotely glorious about it. Everyone is screaming in terror, some soldiers are shivering, people get shot dead out of nowhere. We follow one soldier running, panting, whimpering, seeming to survive out of sheer random luck as strangers and friends alike die in front of him, behind him, beside him, on top of him. He’s not just in over his head. He’s at the bottom of an insurmountable abyss. He pulls out a shovel, screams and hacks at a guy with it like he’s an ax maniac. Cut to title. Cut to a mountain of grey corpses being pulled out, dumped into the mud, undressed.

This is when I knew this was something better than I’d expected. The first thing after the title is a montage that treats dead soldiers as a massive undertaking in garbage disposal and recycling. The corpses are lined up like cars in a junkyard. Coffins are stacked and covered in lyme. Boots are removed and collected in enormous mounds. Huge wads of bloodied uniforms are wrapped in sheets and loaded into trains, then transferred to trucks, then warehouses. They are laundered in huge pools, brought to factories where they are repaired and restitched, then folded, packed up and driven over to suit up the next batch of recruits.

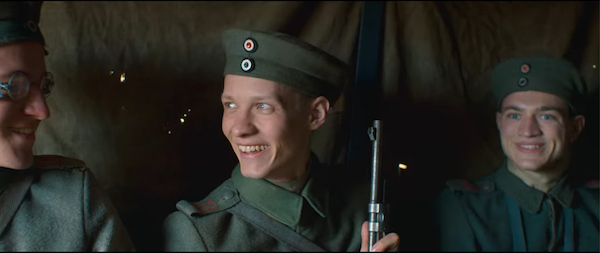

And then we meet some of them. Paul (Felix Kammerer) rides into town on his bike to meet up with his buddies. When these boys talk about going to war it’s exactly like the kids at the beginning of HALLOWEEN H20 talking about going on the school trip. They tease Paul about not being able to go, offer to forge his parents’ signature for him. When he forges it himself they laugh like it’s some fun mischief.

These kids are so pitch perfect. Baby-faced, know-it-all war bros smirking and laughing like the dudes in PORKY’S. They have no idea what they have no idea about. Through the orientation speech and the drive to the front they can’t contain their excitement. They just keep smiling and pumping each other up like they’re off to Spring Break. And when they line up to get their uniforms, Paul’s still has some other guy’s name on it. Heinrich Gerber. “Probably too small for the fellow. Happens all the time,” says the guy at the desk, but we know otherwise ‘cause we saw Heinrich die unglamorously in the opening scene, and have his uniform pulled off him and refurbished.

Before they even arrive at the front a surgeon in a bloodstained coat waves their truck down and makes everybody get out and walk because they need the truck for “40 men dying in the mud.” On their way there a bomb barely misses them and Paul is too slow getting his gas mask on so the sergeant or whatever punishes him by making him wear it the rest of the day. He gains a new hero when they get to the trench and a tough, experienced soldier with a mustache and a cigarette sees the mask, recognizes what happened and says, “Throw a dog a bone it will always snap it up. Give a man power…”

That’s Katczinsky, nickname Kat. He reminded me of Tom Hardy the whole time, but he’s played by Albrecht Schuch (BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ). He’s the mentor, the big brother, the cool older guy who makes them feel like they’ve made it when he’s their buddy.

When they get there it’s pouring rain and they have to use their helmets to try to scoop the muddy water out of the trench. Those big smiles went away fast. They come back briefly when Kat teaches them to warm their frozen hands by putting them in their pants. But for now on their faces will be looking something like this most of the time:

This story is not just about the horrors of combat, or the doldrums of the lulls in between. It’s also stuff like you just got dug out of a collapsed tunnel but you’re not injured so you get sent on the chore of collecting dogtags from the dead bodies, meanwhile figuring out which ones are your buddies from back home and if you start to cry somebody says, “Come on, move along, we don’t have all day,” so you move along to the next corpse.

Somewhere far away, in an office, we see men in ties, smoking cigarettes, piles of tags on their desks, scraping dried mud off to read the names and write them down. The endless processing of the dead, way too many to keep on top of.

From what I understand the subplot about bureaucrats trying to end the war is a new addition to the story. The great Daniel Bruhl (INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS, RUSH, voice of Lightning McQueen in German dub of CARS) plays a diplomat named Erzberger who understands that no good can come of continuing the war and convinces German High Command to begin armistice talks with the Allied powers. I wasn’t sure this movie needed a good guy government official trying to do the right thing, but I think it’s effective because it shows how agonizingly slow it is to negotiate. We’ll be buried in mud and human flesh over there in Hell on Earth and occasionally cut back to these guys with their amazing meals and fancy tea sets. Erzberger seems pretty upset when the vibrations of the train cause him to piss on his boot one time. Boy, this war really is hard on everybody, isn’t it?

During the 72 hours the Germans have to debate between agreeing to the terms or “dying with honour on the battlefield,” Paul’s harrowing experiences include watching his fellow soldiers be flattened under tank treads and set on fire by flamethrowers, and getting trapped in a pit with an enemy soldier who he stabs repeatedly in the chest and tries to choke with mud. But the man lays there twitching and gurgling blood for long enough that Paul starts to feel guilty. He cries, scrubs the blood off his hands with dirt, starts apologizing, calling him “comrade,” cleaning his face, cutting open his coat to get to the wounds he gave him, as if there’s some chance to undo them. When the man dies Paul finds notes and photos of his wife and kids in his coat pocket. A guy with a name and a life and a family Paul knew nothing of. He lays on top of the body, caked in so much mud he looks like a Fulci zombie.

I’d say that movie 1917 had an influence on the battle scenes more than SAVING PRIVATE RYAN did. But I think cinematographer James Friend (Street Fighter: Assassin’s Fist) gives it a modern digital look that feels like a fresh perspective of the subject, not just the same as every other war movie. There’s often an eerie beauty to these war zones lit by flares at night. There’s a great shot of morning sun beams shining through trees, two planes silently dogfighting in the distance, the camera and the characters paying them no mind, like they’re passing dragonflies.

If anything is glamourized it’s the camaraderie of the war bros hanging around and bonding when they get to be away from the trench. There’s a scene where Paul and Kat sneak off and steal a huge goose from a farm, and they cook it and eat it and it seems like the greatest thing they ever ate. The joy is contagious, but we’re also very aware that to the family they stole it from they’re invaders, looters, war criminals.

When they talk about going home they’re not sure it will be any better. One guy dreads having to go dig peat again, and not know for sure if he’ll have a meal. For Kat, being away from war means facing his grief over the young son he lost. He worries they’ll “walk around like travellers in a landscape from the past” and everybody will want to know if they were in close combat. Later Paul complains that he’ll “never be able to clean off the stench” of his experiences, and lists all his friends who died, but Kat says “At least they’re at peace. We’re alive.”

There’s another layer of decision makers keeping them stuck in this besides the negotiators. Macho asshole General Friedrichs (Devid Striesow, DOWNFALL) looks like the bad guy from SONIC THE HEDGEHOG and sees himself as a soldier for life. If he lives long enough he’ll be a Nazi for sure. He guilts another officer about having other things to do in peace time, complains that his father got to be a war hero but he was born during half a century without war. “What is a soldier without war?” he asks as soldiers are being blown to bits nearby and he’s lounging like this:

The darkest irony of the movie is how much happens between when word spreads about the armistice and when it officially begins. Everyone is celebrating the war being over but more people die. SPOILER – Paul and Kat decide to celebrate by taking food from that same farm again, so Kat – Paul’s best friend, and hero, and representation of the soldier he wishes he could be, but could never live up to – gets shot to death by a little kid while he’s taking a piss. Because they stole some duck eggs. Didn’t even get to cook them, just ate them raw. And Paul can’t get anyone to drive him to the medic because everybody’s celebrating the war being over.

Friedrich considers the end of hostilities “a shitty mess,” so he orders another offensive to capture the plains before the war ends at 11:00. You know – for that very important objective of proving they’re “soldiers and heroes,” not “cowards who chickened out when it really came down to it.” Some soldiers say they’re not going, so they get bashed with rifle butts. Paul’s face is pretty different during this rousing speech than the one at the beginning.

So there’s no heroism here. Just an explicitly pointless battle fought by all these soldiers who thought they’d made it out, plus one poor awkward redhead kid freshly shipped to the front lines, against innocent soldiers who also thought it was over. The end of the movie is our protagonist spending the last ten minutes of the war basically doing a mass shooting on some nice French soldiers we just saw toasting that “the nightmare is over” with a dead comrade’s do-not-open-until-armistice wine. Paul bashes a man’s face in with his helmet, nearly gets smothered in a mud puddle, ultimately (SPOILER) gets run through by a bayonet less than a minute before the official end of the war. It’s one of the few war movies where the protagonist is killed and I thought yeah, you earned that, pal.

This is a German film produced and distributed by Netflix. Doesn’t it seem like their international productions are classier than most of their American ones? Maybe that’s just the ones I find out about. Director Edward Berger has mostly worked in television, but this is very cinematic, seems designed for the big screen even though most people would never be able to see it there. Thank you, Academy, for roping me into watching it.

February 13th, 2023 at 7:47 am

I have yet to see this version, but I wholeheartedly recommend the Lewis Milestone/Lew Ayres version. From your description in sounds like a lot was changed (from story details, to character’s ultimate fates), so you won’t be having to sit through exactly the same story again.

The big thing about the 1930 version is it’s very much a ‘they don’t make ’em like that anymore’ movie. In that, I’m unsure how 60-100 people weren’t killed during the production, because it sure as shit looks like they came dangerously close on multiple occasions.