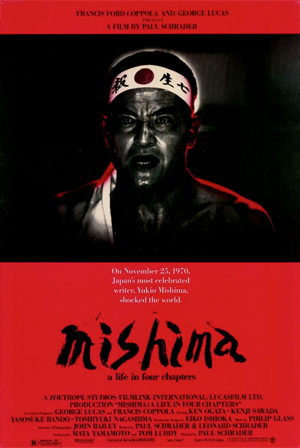

This is the story of Yukio Mishima (Ken Ogata, VENGEANCE IS MINE), once “Japan’s most celebrated author,” but now largely known as a crazy who commited public ritual suicide. Paul Schrader’s complex, lushly produced film weaves together both sides of the writer’s legacy, illustrating what he called “the harmony of pen and sword,” an attempt to fuse his art and his actions into one.

It starts in 1970 the morning of the day when we know from the onscreen text that Mishima is going to take “4 cadets from his private army” to a military base, kidnap a general. Mishima, and those of us who have heard of this incident, know he will make a speech about the soul of Japan and then cut his belly open with a sword. But he doesn’t seem nervous. He skips breakfast but has one last leisurely morning, reading the paper, enjoying some tea in his lovely backyard.

“Recently I’ve sensed an accumulation of many things which cannot be expressed by an objective form like the novel,” says the somehow effective Roy Scheider narration in the English version. “Words are inefficient. So I found another form of expression.” He’s packing up swords as he says this. He ritualistically puts on his uniform, much like William Devane in ROLLING THUNDER or Travis Bickle with his mohawk in TAXI DRIVER, two other Schrader-scripted films about fed up extremists who plot violent sieges to correct what they see as a sickness in the world. (Lucas has not shown this same fascination with extremists, martyrs and ticking time bombs, unless you count his last directorial work, in which the protagonist snaps, violently attacks his own temple and fights his own master.)

“Recently I’ve sensed an accumulation of many things which cannot be expressed by an objective form like the novel,” says the somehow effective Roy Scheider narration in the English version. “Words are inefficient. So I found another form of expression.” He’s packing up swords as he says this. He ritualistically puts on his uniform, much like William Devane in ROLLING THUNDER or Travis Bickle with his mohawk in TAXI DRIVER, two other Schrader-scripted films about fed up extremists who plot violent sieges to correct what they see as a sickness in the world. (Lucas has not shown this same fascination with extremists, martyrs and ticking time bombs, unless you count his last directorial work, in which the protagonist snaps, violently attacks his own temple and fights his own master.)

Mishima is not Bickle, a marginalized loner. He’s a celebrity, and is respected enough to be allowed to train a private army called The Shield Society, intended to bring back the spirit of the samurai to an army run by greedy, spiritually bankrupt politicians. His young acolytes happily join him on his mission, and beg to die with him, as if it would be some great honor they don’t want to get cheated out of. As they get in the car and drive toward their fate, Mishima remembers his youth and then pieces of his famous novels. The movie is divided into four thematic chapters which start with the progress of his pen and sword business in 1970 and then usually branch off into this other stuff. The tangents serve to explain where he’s coming from and how his stories foreshadowed his ultimate act, but also create great suspense by dragging out the buildup to the tragedy.

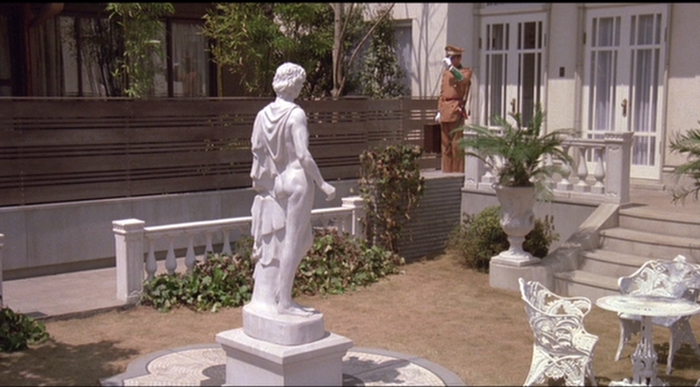

The segments are differentiated by their visual styles. The present is in pretty faded color, mostly mimicking the beige-with-green-highlights of Mishima’s uniform.

The flashbacks are in black and white.

This goes not just for his stories about childhood, but even the more recent, contemporary events that happen before the day of the siege.

The three adapted stories are brightly colored and take place mostly on stylized sets like a stage production, each following a different minimalistic color palette.

In the flashbacks we learn of some of his philosophies and experiences, which are then reflected in the stories to the point that autobiography and fiction seem to meld. The different stories seem to tell one story, his characters sitting in for him in some scenes. We learn of his homosexuality, his masochism, his vanity. As a young boy his sick grandma takes him away from his mother, makes him stay indoors, taking care of her. As a young man he becomes obsessed with beauty and takes up bodybuilding. One of his characters, an actor, does the same. He says his face is too plain for acting, so he wants to be able to use his entire body as his face. Later he tries to protect his mother from loan sharks and does it by becoming kept man to a female gang boss who gets off on cutting him. He feels he’s booked a great gig when they decide to commit a Romeo and Juliet style double suicide. His art and his death become one.

Just as these characters in his story re-enact a Shakespeare play, Mishima ends up acting out one of his stories in real life. In “Runaway Horses” a group of young extremists plan to save Japan with a series of assassinations by sword, then commit seppuku on a cliff with a beautiful view. Schrader cuts away just before the act, not going back to it until Mishima’s own suicide. When we first cut away from it it seems to protect us from something awful, then when we go back to it it’s to protect Mishima from the awful reality of his suicide (which, it is not mentioned in the movie, was a long, messy ordeal where everything went wrong) and give him the glorious idealized one from his story. I only realized later that the gorgeous sunset during the opening credits is the view of the samurai about to commit seppuku on the cliff. So it’s kind of a trick to make us enjoy its beauty. We didn’t have all the information.

Each of the stories involves a drastic, life-changing or life-ending act. One character promises “I’ll make headlines” before a planned arson. Another plans to commit suicide at the supposed height of beauty. Another slices through a wall and tries to kill a government official, thinking he’s saving his country. Schrader is obviously interested in these sorts of extreme characters who decide one day to put it all on the line. Even as recently as DYING OF THE LIGHT, though that was a character going nuclear because he’s sick and doesn’t have much time left.

As a boy, Mishima masturbates to a painting of the Christian martyr Sebastian, bare-chested and pierced with arrows. As an adult he has a photo taken of himself in the same pose. He says that writers are voyeurs, and he wants to change that by being seen. He works out, acts cool, does all these artistic photo sessions, basically tries to be a rock star. At a press conference he says he wants to be Elvis Presley. In stories he writes about wanting to die young, before the body falls apart and loses what he thinks is beauty. So his life-long fascination with martyrdom is complicated. How much is sincere idealism, and how much is self-mythologizing? You can’t really know.

This is by far the most accomplished directorial work I’ve seen from Schrader. It’s so beautifully designed and composed, and every gorgeous shot fits like a tile in a great mosaic portraying this larger idea of the power of art. And it would be an oversight not to mention the great score composed by Philip Glass. Like so many other elements of the movie it is both beautiful and haunting, provoking emotions about what you’re looking at while simultaneously building dread about what you know you’re eventually gonna have to deal with.

This is of course a movie about a real person, but for writers or other artists I think he becomes something of a fantasy figure. I am prepared to vow right here and now to never kidnap anybody or cut my belly open with a sword. But as someone who loves words, who takes my art more seriously than anyone else would take it, who can be very opinionated and stubborn and worried that society is going to shit, I can relate to Mishima in a certain sense. He’s this little piece of me pumped full of Bane juice and amplified into a mythical figure. Though Schrader is in no way justifying Mishima’s actions, I bet some part of him sees a little bit of wish fulfillment in them, the same way Mishima seemed to in his own stories. You want to be pure in your code and you want to know that you truly stood for something and did not compromise.

Lucas did this with Star Wars, by changing his movies to the way he wants them to be, the way he feels they speak for him. And unfortunately, like with Mishima and his address to the garrison, most of us don’t like what they have to say. Luckily Lucas’s self-disembowelment was only symbolic, selling off his shit and retiring. In the Hagakure, the 300 year old Bushido text referenced in both MISHIMA and GHOST DOG, it says, “In the highest level a man has the look of knowing nothing. These are the levels in general. But there is one transcending level, and this is the most excellent of all. This person is aware of the endlessness of entering deeply into a certain Way and never thinks of himself as having finished. He truly knows his own insufficiencies and never in his whole life thinks that he has succeeded. He has no thoughts of pride but with self-abasement knows the Way to the end. It is said that Master Yagyu once remarked, ‘I do not know the way to defeat others, but the way to defeat myself.’ Throughout your life advance daily, becoming more skillful than yesterday, more skillful than today. This is never-ending.”

It does not specify if this is referring to trying to improve your old movies with Special Editions. But in continuing to alter his works over the years, Lucas, like Mishima, was pursuing a personal artistic ideal beyond what is considered acceptable by society. If there is some small part of us that almost admires Mishima’s insane act on a symbolic level then perhaps we could offer the same for Lucas’s act of artistic determination, even as it frustrates us. And, I mean, I feel better for the guys who have to clean up his mess than Mishima’s, even if it’s gonna take longer. Cleaning up intestines < Listening to “Jedi Rocks”

Schrader, having also come up in ’70s independent cinema, shares Lucas’s uncompromising approach to filmmaking. Of course, not having the hits under his belt or the money in the bank he has lost some of his battles (DOMINION: THE PREQUEL TO THE EXORCIST and DYING OF THE LIGHT come to mind). MISHIMA, in part because of Lucas’s backing, was one case where Schrader clearly won. In an interview on efilmcritic.com, Schrader explained how Lucas – like with so many other movies in this series of reviews – convinced a studio to put money into a movie they knew they wouldn’t make money off of:

“Francis was producing but he couldn’t get anybody to help us out from the U.S. side, so we went to George. George had kind of a rocky relationship with Warner Brothers but he said that he would be willing to take this on. He went to Warners and at the end of that conversation, Terry Semel, who was the head of Warners, said to George, ‘If we do this, will we be doing you a favor?’ George said yes and so they agreed to match our Japanese money. It was done to ingratiate Warner Brothers to George, basically. They never had a great deal of interest in promoting the film–their obligation was fulfilled when they put up half the money and that is why there was never really a big promotion for the film.”

Watching the Lucas productions all in a row, it’s hard to miss that MISHIMA’s complex structure based in four parts and using changes in visual style to cue the viewers to the different segments has alot in common with the form Lucas devised for MORE AMERICAN GRAFFITI. But since I haven’t found any evidence of Lucas working with Schrader during the planning stages I’ll assume this is just a coincidence. Or that Schrader was the one guy that liked MORE AMERICAN GRAFFITI back then. But Lucas’s involvement did go beyond funding according to the book Whom God Wishes to Destroy: Francis Coppola and the New Hollywood. “Signing on before Coppola had even secured the rights to the Mishima estate,” writes Jon Lewis, “Lucas eventually provided postproduction expertise at his amazing facility in Marin County and helped market the film.” This is a masterful film, so with the former, at least, he delivered in spades.

December 17th, 2015 at 2:19 pm

Great review of a truly great film.

Such a shame Mishima was the film that finally killed stone dead the personal and artistic relationships between Paul Schrader and his brother Leonard.

Their first feature, 1974’s The Yakuza, is a must see for all you guys. Just beautiful.