May 25, 1983

May 25, 1983

Nobody was surprised that the movie of the summer, and of the year, was RETURN OF THE JEDI. It was the thrilling final(ish) chapter to the biggest pop culture juggernaut in the world, it was the ultimate summer popcorn movie, the movie others had to get out of the way of, or ride the coattails of, and of course became by far the highest grossing movie of the year (trailed by TOOTSIE in second place).

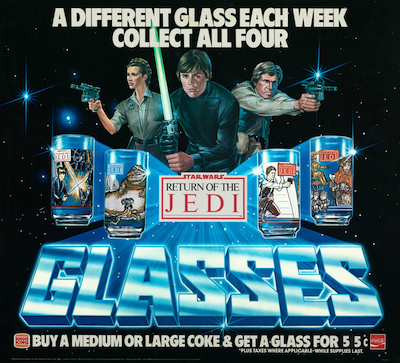

It’s one of the two movies I remember seeing in a theater that summer. That was monumental because I’d seen the other two at the drive-in while very young, but this one I was able to see with slightly more awareness of what was going on, and I’d bet the crazy discussions we had of it later on the playground were a little closer to what actually happened in the movie. Not that I was all that savvy. I remember my family went to Burger King after the movie and got RETURN OF THE JEDI drinking glasses, which seemed like a coincidence. Hey, this is the movie we just saw! What are the chances?

It’s one of the two movies I remember seeing in a theater that summer. That was monumental because I’d seen the other two at the drive-in while very young, but this one I was able to see with slightly more awareness of what was going on, and I’d bet the crazy discussions we had of it later on the playground were a little closer to what actually happened in the movie. Not that I was all that savvy. I remember my family went to Burger King after the movie and got RETURN OF THE JEDI drinking glasses, which seemed like a coincidence. Hey, this is the movie we just saw! What are the chances?

That’s the sort of thing I intentionally avoided talking about when I reviewed RETURN OF THE JEDI nine years ago as part of my “Star Wars No Baggage Reviews” series. The rule was that I had to look at episodes 1-6 as they existed at that time, in the current George Lucas-approved cuts, as if there had never been any other way to look at that story. I couldn’t complain about any Special Edition alterations, or lean on childhood nostalgia, or disappointment about the prequels not being what we’d dreamed of. It was a fun exercise designed to jettison all the stuff people usually discussed about those movies, things I was sick of hearing or talking about, and I think it was a worthwhile experiment that turned out well.

For this revisit of RETURN OF THE JEDI in the context of the summer of ’83, though, I won’t give myself those constraints. I’ll try not to get hung up on any bullshit.

For this revisit of RETURN OF THE JEDI in the context of the summer of ’83, though, I won’t give myself those constraints. I’ll try not to get hung up on any bullshit.

We can get the alteration stuff out of the way quickly: this is the one where Lucas’ 1997 Special Edition changes bother me the most. I’m not a fan of the new musical number in Jabba’s palace, and I respect what he was going for at the end, showing victory celebrations on other planets, but I miss the Ewok song. I still have the limited edition DVDs with the non-anamorphic theatrical cuts, but the blu-rays look so much better that I usually hold my nose and watch those. However, for this latest viewing a friend downloaded a fan-made transfer of a 35 mm print, which was absolutely great. That’s the movie to me. So we shall speak no more of “Jedi Rocks.”

The main thing I want to discuss in this review is why the part 3 considered by many to be the worst of the original trilogy would be, if forced to choose, my personal favorite Star Wars movie. I understand why most people prefer THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK – the Hoth sequence is perfect, the Yoda scenes are the best thing in the whole series, Cloud City is cool, I think it’s the best looking as far as lighting, and the interplay between Han and Leia is fun. It’s a great, great movie.

The main thing I want to discuss in this review is why the part 3 considered by many to be the worst of the original trilogy would be, if forced to choose, my personal favorite Star Wars movie. I understand why most people prefer THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK – the Hoth sequence is perfect, the Yoda scenes are the best thing in the whole series, Cloud City is cool, I think it’s the best looking as far as lighting, and the interplay between Han and Leia is fun. It’s a great, great movie.

And there’s a weakness to JEDI that my wife has made me keenly aware of. She loves it too, but she tells me that growing up she found it very disappointing that her favorite character, Princess Leia, didn’t have anything to do during the big finale. To this day she loves that Leia kills Jabba, rides a speeder bike and feeds Wicket a rice cake, but she doesn’t like that in the last act she’s just kind of around. The heavy-lifting she has to do is emotional stuff about her relation to Luke and Vader, stuff that plays as pretty silly after you’ve seen it a few million times, so that doesn’t help. (For her part, Carrie Fisher complained about not having dialogue while enslaved by Jabba, abandoning the defiance Leia was known for in the other two films. She claimed that filming those scenes inspired her to become a writer.)

Intellectually I can also understand complaints that having another Death Star as the big weapon is an unimaginative choice, but having had the movie imprint on me at the age of 8 it’s impossible to be deeply bothered by that. I tend to agree with Lucas’ thinking, as expressed in story conference transcripts in J.W. Rinzler’s incredible coffee table book The Making of Return of the Jedi, that a quickly understandable mcmuffin is preferable to a new weapon they have to spend time explaining, since what they’re blowing up to defeat the Empire is not the point of the thing. (And the trojan horse twist that it’s made to look unfinished but is actually operational is a nice touch.)

Finally, as I wrote in the other review, I hate the part where Chewie’s roar is pitch-bent to sound like a Tarzan scream. What kind of a joke is that? In so many other ways, though, RETURN OF THE JEDI is Star Wars at its best. It’s the ultimate in that surface level appeal of Star Wars as movies jam-packed with dazzling special effects, imaginative creatures, detailed worlds, speed and momentum. It has by far the most puppet creatures, the most model work, the fastest analog-FX chase sequence, the best original trilogy saber fight (shout out to Yoda for teaching Luke to do flips). But at the same time, as the climax of the original trilogy it has so much of the juicy emotional and thematic stuff. It’s the one where Luke redeems Vader by refusing to fight him! To me that’s the main point of the trilogy, even more so when it became a hexalogy.

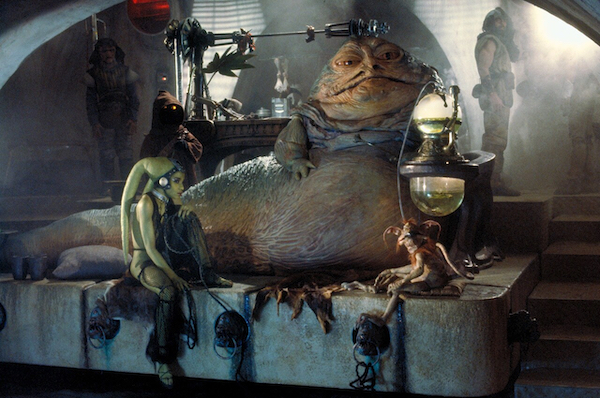

It’s the Star Wars with the most cool stuff in it. If you don’t think so, you must be taking Jabba the Hutt for granted. This crimelord we knew Han owed money to, and who Boba Fett captured him for, could’ve just been a guy, but he turns out to be one of the all time great movie monsters. I’m not an anti-c.g. guy at all, but few digital creations seem as alive as this enormous rubber slug puppet (with three operators inside moving the arms, head, tongue, and tail, one below moving his mouth and making his sides heave, and others remotely controlling his eyes).

And it’s not just that he looks cool, it’s also that he’s such a great character – his tired eyelids, slimy mouth, the way he puffs on a hookah, his deep, booming laugh and slow, subtitled speech. The way he surrounds himself with dancers, slaves, toadies, hangers-on, dancers, a house band. The cruelty of throwing both employees and enemies to the enormous Rancor that he keeps in a dungeon below (another great movie monster). And of course that little moment when Luke has killed the Rancor in self defense and its keeper cries and is consoled by a colleague. Those guys know he was just an animal and maybe know that he was a victim of Jabba as well. Like a dog trained for fights.

And there’s something extra fun about the heist movie format of this sequence. We know they need to rescue Han from the palace, we don’t know how they plan to do it, and we see each step of the plan (or really a series of backup plans, it seems) unfold without foreknowledge of what they’re up to exactly. Artoo and Threepio arriving as messengers, showing the hologram of Luke, at least one of them not knowing he’s offering them as a gift to Jabba. Then the masked bounty hunter showing up with captured Chewbacca, impressing Jabba with his threat to blow him up, but really being Leia in disguise, then being captured herself. Then Luke showing up in person, being waylaid by a plunge into the Rancor pit, being taken out to walk the plank and then turning the tables.

I’ve been asked before how they actually wanted it to go. I take it as a series of things to try but always with another idea in place when it doesn’t work. According to the Rinzler book, in Lucas’ pre-Kasdan-rewrite rough draft, “It’s clear that his goal is to trick Jabba into the open, where it will be easier for Luke to do battle as a trained Jedi.” And the book includes transcripts where Kasdan says, “You can assume that Luke’s plan is multilayered and the court of last resort is they are going to take him to the Sarlacc pit and they’ll all be in place. But when he comes in and says, ‘I want to bargain for Han,’ he is hoping that will work.”

“Yes,” Lucas says.

More undeniable cool stuff: the speeder bike chase on Endor. The rebels are there to blow up a shield generator for the Death Star, they’re spotted by stormtroopers and need to take them out before they warn the others, so they steal high speed hovering vehicles and pursue them through the forest. I remember this being a huge deal at the time, watching and reading about how they did it, a combination of green screen of the actors over moving footage, some miniatures, and sped up steadicam shots weaving through trees, deftly edited to create a riveting, if mostly artificial, action sequence. Steadicam operator Garrett Brown had done the same for THE SHINING, so he’s a legend. Joe Johnston and Dennis Muren mapped it out in an animatic using Star Wars dolls and action figures in a miniature forest that included some trees left over from E.T.

Note that there’s no score in this scene – John Williams wasn’t necessary to get our hearts pumping, and this way we really hear the engines, the blaster shots, the near misses, the crashes and explosions.

And then there’s the Ewoks. I’d offer them as another self-evidently cool part of the movie if I didn’t know there were so many who consider them the obviously terrible part. Of course I didn’t know about those people until I got older, because what kind of a monster would like Star Wars but not Ewoks? It doesn’t compute to a person my age, but it’s a widespread and persistent sentiment.

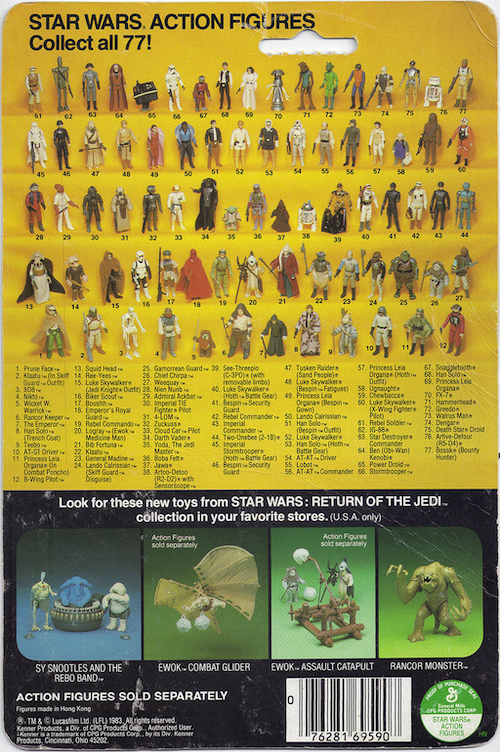

What I’ve concluded over the years is that the anti-Ewok contingent is led by people who were teenagers in ’83, and have never let go of their “I’m a grown up now, and this is for babies” reaction to them. They contend that because there were Ewok dolls and a cartoon that they were designed to sell toys and therefore bad. Of course they’re also aware that Lucas was able to self-fund EMPIRE and JEDI because of his shrewd licensing deals, and there’s a 300% chance that these same people will, at the drop of a hat, wax lovingly about which STAR WARS or EMPIRE action figures, shampoo bottles and pajamas they owned as kids. Many of them have even bought some of that kind of stuff in the decades since, but they mentally separate that from their anger at these particular characters in the second half of the third movie for being “just made to sell toys.”

A character actually affected by potential toy sales was Rebel Alliance General Madine. When Kenner executives visited the set they were adamant that he have a beard, since they’d already made his action figure with one. But he’s not very cute, while Ewoks are “too cute” according to detractors. They do not hold cuteness against Jawas, Chewbacca, Droids (who also had a cartoon), Yoda, or their own pets or children, but they hold it against the Ewoks. It’s not only selective, it’s also missing the plainly obvious entire idea of the Ewoks: that they’re cute at first glance but then turn out to be savage little bastards who trap our heroes and attempt to cook them. Even after they’ve turned out to be great allies and heroic saviors of the galaxy there’s that one who gleefully plays drums on the (empty?) helmets of soldiers they killed in the battle. Yeah, they kinda look like teddy bears, that’s why motherfuckers underestimate them. That. Is. The. Joke.

It’s like getting mad at the killer dolls in BARBARELLA for being dolls. Why did they have to be little dolls biting your face off? Why not a big menacing thing? Wouldn’t that be better? No. It would not.

The other thing about the Ewoks is that they’re the culmination of one of the themes of the trilogy. Many of Lucas’ ideas were steeped in his generation’s response to the Vietnam War and Watergate. He likened the Ewoks to the Viet Cong, as did director Richard Marquand (who I’ve read had done documentaries on the war, though I haven’t been able to determine which ones). That’s not a one-and-one analogy, obviously, but they’re a sci-fi version of locals rising up in guerrilla warfare.

The other thing about the Ewoks is that they’re the culmination of one of the themes of the trilogy. Many of Lucas’ ideas were steeped in his generation’s response to the Vietnam War and Watergate. He likened the Ewoks to the Viet Cong, as did director Richard Marquand (who I’ve read had done documentaries on the war, though I haven’t been able to determine which ones). That’s not a one-and-one analogy, obviously, but they’re a sci-fi version of locals rising up in guerrilla warfare.

In STAR WARS, Luke in his tiny little X-Wing took off his goggles and trusted in his instincts/The Force to make the one-in-a-million shot that destroyed the Death Star. Here this physically small indigenous tribe defeat the technologically superior Imperial army using rocks, spears, arrows, logs and gliders.

That meaning is obvious and important, but I think these guys would be cool anyway. Seeing small creatures in an underdog battle against stormtroopers on speeder bikes and in their huge mechanical walkers, taking them out with trip ropes, booby traps and hang glider bombings – what is there not to love about that? How does one enjoy this type of movie, but not appreciate that? It’s invested with extra drama by that incredible moment when two Ewoks get knocked down and one tries to help his friend up only to find him unresponsive. But again, even without that highlight, this would be a great battle sequence. I’m not budging on this, it’s science.

I’m pro-Ewok and I vote. I stand with the Ewoks. #EndorStrong

It’s also the one with the most elaborate space battles of the analog era. Time reported that JEDI had 942 “special effects” as compared to STAR WARS’ 545, explaining the techniques like this:

“The scenes in space were the product of highly advanced matte photography. One element of a scene, an imperial battle cruiser, for instance, would be shot. Then another element, like a rebel fighter, would be photographed and superimposed on it, as if it were another layer on a cake. Some of the shots in the final space battle had 67 such layers, one on top of the other.”

That answers my question, sort of, about how they put so many moving space ships together in the same shot. Watching that 35mm transfer was exciting because in the Special Edition you know some of the shots have been replaced or altered, but watching that I found myself thinking oh shit, I forgot they could do that back then.

After the trench run in the first film, the space battles have rarely been my favorite parts of Star Wars films. They’re great, of course, they’re just not as great as the other stuff. So I love that this more elaborate and technologically sophisticated version of the first film’s space battle plays in the background of two other conflicts: Han, Chewie and Leia on the ground with the Ewoks in Endor, and Luke and Vader (who were facing each other from inside cockpits the first time) meeting IRL, battling physically, mentally and spiritually with each other and the Emperor.

Also there’s some extra color to the space battles added by having a great alien character leading the rebels. Nothing against Mon Mothma or some guy with a beard, but obviously having a weird lobster man at the helm is more exciting. In the Rinzler book we learn that when Lucas realized Admiral Ackbar didn’t need to be human, he asked Marquand to pick “who’s going to play Admiral Ackbar” from all the unused alien designs. Marquand chose “the most delicious, wonderful creature out of the whole lot” because “I think it’s good to tell kids that good people aren’t necessarily good-looking people and that bad people aren’t necessarily ugly people.” He said that a few present thought it was a terrible idea and “People are just going to laugh when they see this guy.” But here we are 40 years later and it never occurred to me he could’ve been anything else. I’m glad he wasn’t!

JEDI is the one where the Emperor becomes a real character, with the indelible performance of Ian McDiarmid, a Royal Shakespeare Company vet who’d had a small part in the recent ILM project DRAGONSLAYER. The mystery of who this emperor was is another aspect I didn’t latch onto at the age I was as these movies came out (in fact I had a hard time understanding that there was a “main bad guy” above Vader), but watching it now he’s such a great personification of the evil of the Empire and the dark side – physically repulsive, seems kinda pervy, openly takes lip-smacking delight in what a bad guy he is, believes he can force Luke to do his bidding even while straight up telling him what that bidding is, shoots enough lightning from his hands to show us flashes of Vader’s skeleton. McDiarmid wasn’t even 40 yet, but Marquand had seen him on stage playing old Howard Hughes under makeup, and correctly guessed he could play this decrepit monster to slithering perfection.

Crucially, JEDI is also the one where Luke is the coolest. He’s matured from whiny farm boy to trusted rebel and now to self-declared Jedi Knight. Hamill seems much more grown up and capable, he wears black, he comes into Jabba’s palace with that hood on, he has more fight moves and force powers than before, and carries himself with confidence. When it looks like he’s painted himself into a corner he offers Jabba one last chance to let him go, causing the vile gangster and his posse to laugh at him, but they quickly see that he does in fact know exactly what he’s doing.

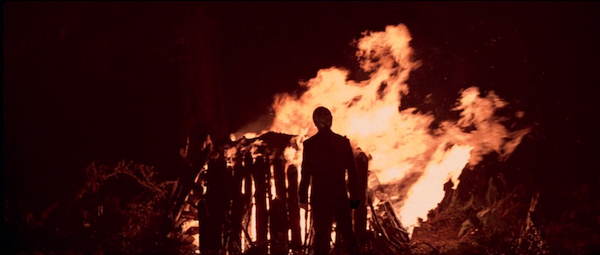

His growth goes beyond being a badass, being good at fighting. He wins the war by believing in his father’s redemption and refusing to fight him. In fact he throws his light saber away and takes a torturous amount of Force lightning from the Emperor, an act of endurance that awakens Vader’s humanity. Some reviews at the time complain about shifting pop culture’s greatest villain Darth Vader to second banana status under the Emperor, but this is one of the movie’s most original and profound choices. We still get the victory over the bad guy, but the trilogy climaxes with Vader making peace with Luke, smiling at him, and dying in his arms – did anybody predict that? I doubt it. It’s beautiful.

Man, Luke really loses those father figures though. First Uncle Owen, then Obi Wan, then Yoda, then Vader. Chief Chirpa is the only elder he has left at the end, other than ghosts.

By now everyone has heard the trivia that Davids Lynch and Cronenberg were considered as possible directors, but turned it down. In the Rinzler Lucas says the list had 20-30 names on it after half were eliminated for not wanting to do a Star Wars movie. Two names mentioned in the book that I’d never heard before are John Carpenter and Tony Scott. But Lucas wasn’t exactly looking for a visionary. He wanted someone with TV experience, recognizing that a director having to work under a hands-on executive producer was closer to that model. He mostly considered English or Australian directors because he was feuding with the DGA, who had tried to fine him $250,000 for putting the Lucasfilm logo at the beginning of EMPIRE, claiming it counted as a director credit. That’s also why he didn’t try to talk EMPIRE’s Irvin Kershner into it.

And yet when he’d narrowed it down to a Welsh director and an American who was in the DGA, he chose the American, David Lynch. Lynch says he wasn’t interested, and when people tell the legend they like to imagine it as a “what the fuck is this bullshit?” type of situation. But according to producer Howard Kazanjian in the book (from an interview conducted at the time), “I called David Lynch and he was thrilled—but within three days he declined… Not long afterward David announced that he was going to do DUNE. So obviously he was being simultaneously romanced by De Laurentiis.”

The Rinzler book describes Marquand’s job with detail and nuance. Some of the crew felt sorry for him having to operate with Lucas over his shoulder, though he seemed to take it very well for the most part. Lucas wrote the script, did all kinds of designing and planning before Marquand was even hired, and since the director was inexperienced with special effects Lucas decided to be on set as much as possible. (Time estimated about 60% of the schedule.) Lucas shot some of the second unit and also reshot work by other second unit directors since what was needed for the FX team was much clearer in his head. Marquand said that his job was to serve Lucas’ vision, comparing himself to a conductor guiding an orchestra to perform the work of a great composer. But he expressed frustration with Lucas making him shoot everything with multiple cameras to allow more leeway in the editing, which he felt disregarded all the planning he’d done ahead of time. Still, he swore that Lucas gave him the final say on everything, and Hamill agreed that Marquand was always “captain of the ship.”

I don’t know how long it took fans to start grumbling, but RETURN OF THE JEDI was generally well received upon release. Roger Ebert gave it 4 stars, opening his review talking about the crying Rancor keeper. “Everybody loves somebody,” he writes. “It is that extra level of detail that makes the Star Wars pictures much more than just space operas.” He called it “a complete entertainment, a feast for the eyes and a delight for the fancy… a very special work of the imagination.”

Across town Gene Siskel also gave it 4 stars. In The Washington Post, Gary Arnold wrote that “It was worth the wait, and the work is now an imposing landmark in popular culture… To put it another way, RETURN OF THE JEDI is rather obviously (but irresistibly) calculated to permit a reunited STAR WARS family — filmmakers and spectators alike — to have their cake and eat it. If the confection appealed to you in the first place, there’s certainly no reason for rejecting this lavish climax.”

Sheila Benson wrote in the Los Angeles Times that “The Jedi return to us at last, older, wiser and frankly irresistible.” She predicted that kids, “with their wriggling love of the really gross” would love Jabba the Hutt while “Adults, on the other hand, are likely to fall heavily for the small, furry Ewoks.”

Philip Strick of Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, “If the revels of Star Wars are indeed now ended, Jedi couldn’t have been a better resolution for them… the film sparkles crisply from one peak of action to the next.”

In Time magazine Gerald Clarke called it “a brilliant, imaginative piece of moviemaking.” He wrote, “It is not as exciting as STAR WARS itself, which had the advantage of novelty. But it is better and more satisfying than THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, which suffered from a hectic, muddled pace, together with the classic problems of being the second act in a three-act play.” He says it has “one of the corniest conclusions in recent years” but that “Despite its shortcomings, which are relatively minor in context, the film succeeds, passing the one test of all enduring fantasy: it casts a spell and envelops its audience in a magic all its own.”

The same article quoted Steven Spielberg as saying, “I think JEDI is the best Star Wars movie ever made, and it is definitely going to be the most successful. The first movie was the introduction; EMPIRE was the second-act conflict. But they were mere canapes for this third-act opus. This is the definitive Star Wars.”

The trades were more reserved. Variety’s James Harwood wrote, “The good news is that George Lucas and Co. have perfected the technical magic to a point where almost anything and everything —no matter how bizarre—is believable,” but “the human dramatic dimensions have been sorely sacrificed.” Though the Hollywood Reporter’s Arthur Knight acknowledged that “Its special effects advance the state of the art by a couple of light years, its settings are not only huge but hugely impressive, and the costuming is rich and imaginative,” he also lamented that “there’s a kind of desperation about it” and “the stuff of legend that inspired and elevated the earlier episodes has here been replaced largely by the stuff of comic books.” He reminisces about the “dizzying light show” of STAR WARS, but claims that “In JEDI there are so many light shows, so many pyrotechnical displays that the eye quickly becomes jaded.” He makes one questionable claim about Jabba, that he “enjoys shrinking people to bite size then popping them into his cavernous maw,” which I have now learned was a common misunderstanding among children because Jabba is shown eating a frog right after he drops Oola through the trap door.

A few critics did trash the movie, including David Ansen and Dave Kehr. Pauline Kael claimed it was “packed with torture scenes” and Vincent Canby called it “by far the dimmest of the lot,” saying that “The film’s battle scenes might have been impressive but become tiresome because it’s never certain who is zapping whom with those laser beams and neutron missiles.”

Leave it to the genre press to be the most finicky. Cinefantastique (one of my favorite magazines despite hosting many of the grouchiest critics around) ran side by side positive and negative reviews, and even the positive one (by Joseph Francavilla) starts off saying “It’s probably useless to complain about the simplistic ideas and flat characters in RETURN OF THE JEDI, the illogical plot developments, the insufferable cuteness or ludicrous repulsiveness of the aliens, the improbable scenes of Leia strangling Jabba or the Ewoks defeating the invincible Imperial technology with primitive weapons, and the impossible ‘sound’ of explosions in the vacuum of space.That would be like expecting profound world literature in comic books.” At the end he bizarrely complains that “In the two prints I saw, the film was scratched or marked in the scene where Vader first steps out of his ship and also where the Emperor first arrives to give his men a ‘forceful’ pep talk,” and then nitpicks other shots he says have visible matte lines or wires.

The thumbs down review by Michael Mayo calls it “an empty movie… a flaccid tale that deals only in vague generalities because Lucas can’t seem to imagine anything specific to do with either emotions or people… the dead-end narcissism of a filmmaker trying to disguise his hate of the whole process with the collaboration of an audience self-hypnotized into believing this is the Real Thing… By turning his back on intelligence and artistic integrity, he has become the king of furry midgets, plastic toys and ten year olds. I hope he enjoys what he’s built.”

In a side bar of capsule reviews, 5 contributors gave it either 3 or 4 stars out of 4, except for future Video Watch Dog editor Tim Lucas, who gave it 2 and called it “perfunctory” and “philosophically Californian.” But a side article by editor Frederick S. Clarke argues that “the makeup illusions provided by the company’s newly instated ‘Monster Shop,’ supervised by Phil Tippett, don’t hold a candle to recent accomplishments in the field.” The article says that makeup veterans Dick Smith and Stan Winston both turned down the job because they would’ve been required to relocate their shops to San Rafael to be near ILM. Clarke disapproves of choosing stop-motion genius but non-makeup-guy Tippett to be in charge, while acknowledging that “his work was exceptional” with puppet characters such as the Rancor. He claims everything else “fell flat,” giving only “the stiff, inexpressive” Gamorrean Guards as an example.

People who disagreed with Cinefantastique on that include The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, who included Tippett with Richard Edlund, Dennis Muren and Ken Ralston in a “Special Achievement Award for Visual Effects,” and the Saturn Awards, which gave Best Make-up to Tippett and Stuart Freeborn. (JEDI was also nominated for art direction, original score, sound effects editing and sound Oscars, losing to FANNY AND ALEXANDER for the first and THE RIGHT STUFF for the rest.) But I found that article interesting to read 40 years later as a cautionary tale for us know-it-all film writers who get hung up on things outside of the movies. Here’s a case where some inside baseball convinced the founder of one of the great genre magazines that ILM totally blew it with the creatures in RETURN OF THE JEDI. It’s a powerful reminder to those of us who write about movies to be very sure we’ve crawled all the way out of our own ass before settling down at the keyboard.

On the other hand, maybe everyone was doing their job there. JEDI was a sci-fi/fantasy/space movie good enough for the mainstream critics not to turn their noses up to it, so they did the right thing, they got dazzled by a dazzling movie. And Cinefantastique came to it from a different angle as the very serious grown ups who knew genre movies and were gonna cut ‘em open with a scalpel to make sure everything was in order. These guys weren’t trying to be cheerleaders for “geek culture” like the later Ain’t It Cool generation, they were trying to be scholars. Veterans of mimeographed fanzines growing into authors of obscure reference books you’d find at the library. They did not skip into theaters looking for “geekgasms,” they sat with their arms folded and their brows furled, vaguely open to the possibility of being impressed. I don’t like it or relate to it when they seem totally joyless, but I’d rather read grumpy but insightful than enthusiastic but empty.

I’ll never know how to look at RETURN OF THE JEDI from that perspective, because I’ve already lived five times as much life with it as I ever did without it. Some complaints in the 1983 reviews seem comical now – it’s like, “Sorry, bud, this is settled law. We’re not gonna entertain your idea that Jabba is too gross.” Meanwhile, some of the complaints about the characters and the story I’m now able to step back and say, “Okay, yeah, I can see that.” And yet it’s impossible for those things to bother me. The movie dug too deep into my imagination, the two got tangled up, like two trees growing too close together.

The whole Star Wars saga is inspired by myths and fairy tales, and to me it has become one. I accept the broad strokes of the story – Luke’s father is Vader, his sister is Leia, Yoda sends him to confront Vader to become a true Jedi, the Emperor thinks if he kills Vader the opposite will happen, he will come over to the dark side. But he refuses to kill Vader, which brings Vader away from the dark side, and redeems him. The return of the Jedi.

Around and in between those story points, different meanings and understandings grow. In that sense – apologies everybody, I’m gonna say it – it’s Biblical. As a literal story, much of it is hard to swallow. Vader was, at minimum, involved in blowing up Leia’s planet. And he strangled some co-workers and tortured his secret daughter. Would you really consider a guy who did that redeemed so quickly? In the real world, no, but this is not the real world. It’s working on a more operatic level. We accept that this is the story, even if it doesn’t make sense, so now how do we interpret it? In our world we can aspire to Luke’s compassion and non-violence, to Vader’s change, to Luke’s forgiveness, and this is an allegory about that, not a prediction of exactly what it would look like.

On this latest viewing I was most captured by that climax and the question of whether or not it was the lesson Yoda intended Luke to learn. Yoda says, “You must confront Vader. Then, only then, a Jedi will you be. And confront him you will.”

Luke assumes that means to kill Vader, and Ben seems to take it that way too. When Luke tells Ben, “I can’t kill my own father,” Ben says, “Then the Emperor has already won.”

But Ben is wrong. Luke defeats the Emperor specifically by refusing to kill his own father. So my question now is, did Luke save the day by disobeying Yoda and finding a better way? Or was Yoda deliberately ambiguous so that Luke would have to find this solution on his own, thus becoming a true Jedi? And if that’s what it is, then is this lesson officially the Jedi way, or is it Yoda’s new take on it after the failures of the Jedi order and their war that sent him into exile in the swamp? Maybe Yoda changed his philosophy late in life, like Malcolm X did. That’s a reading informed by my interpretation of what happens in the prequels, but I think it also fits with what we know of the backstory just from this trilogy.

I like that RETURN OF THE JEDI has enough on its mind, and enough empty space in between, for me to keep thinking about it different ways 40 years later. Also I like that it has Jabba and speeder bikes and Ewoks. It’s not deep, it’s not kiddy fluff, it’s both, somehow. I think that makes it a great movie. Celebrate the love.

Tie-ins: I trust I don’t have to list all the RETURN OF THE JEDI merchandise and video games and shit that exist. There was a bunch. I will mention that the novelization came out two weeks before the movie (SPOILER ALERT!) and was written by James Kahn, who has an interesting biography. He went to medical school and then trained and worked in various emergency rooms but worked as a writer on the side. When he and his department were contacted to work as medical consultants on E.T. he ended up playing the doctor who declares E.T. dead. On set he gave one of his sci-fi novels to Spielberg, which got him the gig writing the novelization of POLTERGEIST. That led to RETURN OF THE JEDI followed by INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM, THE GOONIES and POLTERGEIST II: THE OTHER SIDE. He also wrote for TV shows including Star Trek: The Next Generation and Xena: Warrior Princess for many years, then became a folk musician. Not bad!

Tie-ins: I trust I don’t have to list all the RETURN OF THE JEDI merchandise and video games and shit that exist. There was a bunch. I will mention that the novelization came out two weeks before the movie (SPOILER ALERT!) and was written by James Kahn, who has an interesting biography. He went to medical school and then trained and worked in various emergency rooms but worked as a writer on the side. When he and his department were contacted to work as medical consultants on E.T. he ended up playing the doctor who declares E.T. dead. On set he gave one of his sci-fi novels to Spielberg, which got him the gig writing the novelization of POLTERGEIST. That led to RETURN OF THE JEDI followed by INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM, THE GOONIES and POLTERGEIST II: THE OTHER SIDE. He also wrote for TV shows including Star Trek: The Next Generation and Xena: Warrior Princess for many years, then became a folk musician. Not bad!

The Ewoks, including Warwick Davis as Wicket, returned in November of the following year with the ABC TV movie THE EWOK ADVENTURE (a.k.a. CARAVAN OF COURAGE). Its superior followup, EWOKS: THE BATTLE FOR ENDOR first aired in November of ’85. A few months earlier, The Ewoks and Droids Adventure Hour – two cartoon shows produced by Canada’s Nelvana animation (ROCK & RULE) – began airing on ABC Saturday mornings. Droids lasted for one 13 episode season (plus a special) while Ewoks last two seasons, totaling 26 episodes. The Ewoks win again.

May 25th, 2023 at 3:41 pm

Great review, Vern. As a lifelong fan of Wars amongst Stars, I could probably say a lot about the movie but very little of it would be new. I do want to add that I think some of the Ewok hate probably comes from people later learning that the original thought was to supposedly have the Ewok sequences actually take place on Kashyyr (spelling?) and instead of Ewoks we would have had wookies. While I am not by any means an Ewok hater (yes I still have my Wicket action figure), I can see how someone might be outraged that a tribe of arm-ripping wookies got replaced by cute ewoks and I could see those people thinking that the switch only happened to make cuter toys regardless of whether any of those rumors are true or not. But also it’s Star Wars, so at least 70% of the fan base needs to have something to complain about in each movie, tv show, comic book, lunch box, lego set, etc.