FROM THE VERN VAULT: Don’t worry friends, I’m not about to start doing reruns all the time, but there are two pieces that were written for One.Perfect.Shot that disappeared after they were bought out by Film School Rejects. Prompted by Rumsey Taylor I located them on Internet Archive and I’m reposting them for posterity.

FROM THE VERN VAULT: Don’t worry friends, I’m not about to start doing reruns all the time, but there are two pieces that were written for One.Perfect.Shot that disappeared after they were bought out by Film School Rejects. Prompted by Rumsey Taylor I located them on Internet Archive and I’m reposting them for posterity.

Maybe I’m full of it but it seems to me this piece from October 26th, 2015 was a little ahead of the curve. At the time I knew of no one else who considered CANDYMAN the best horror movie of the ’90s and I didn’t think people talked enough about its exploration of the legacy of slavery in America. I’m proud of this as well as my 2005 take on the movie. (It’s not dangerous until I review it five times, is it?)

P.S. I am responsible for the headline but that term “the racial divide” bugs me now – I wish I called it “WE’RE NOT COPS – WE’RE WITH THE UNIVERSITY.”

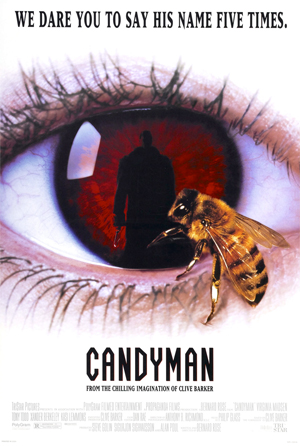

‘CANDYMAN’ AND THE RACIAL DIVIDE: WHY ONE OF THE BEST HORROR FILMS OF THE 90S IS EVEN MORE RELEVANT TODAY

“These stories are modern oral folklore. They are the un-self-conscious reflection of the fears of urban society.” –urban legends lecture by Professor Lyle (Xander Berkeley)

“What if a person had this thing done to him and what if he had the opportunity to come back and say, ‘Watch out!’ to the world that created this person and the conditions?” –Tony Todd to Fangoria Magazine, March 1995

American horror movies have played off of all manner of primal and societal fears: tensions between social classes, the invasion of the sanctity of the home, the dangers of trespassing in forbidden places. But leave it to a couple of British artists – writer/director Bernard Rose and executive producer/short story author Clive Barker – to explicitly tie those themes to the racial atrocities of our history, creating a truly American horror story.

In CANDYMAN, Virginia Madsen stars as Helen Lyle, an ambitious (and white, it’s relevant to mention) graduate student at the University of Illinois. She’s working with her partner Bernadette (EVE’S BAYOU director Kasi Lemmons) on a thesis about urban legends, and one of the stories they’ve studied is about a hook-handed killer called Candyman who’s supposed to come after you if you say his name five times in front of a mirror. When Helen discovers a real murder with parallels to the Candyman legend she finds herself snooping around a crime-ridden low income housing project and being courted by the avenging ghost of a tragic figure from the reconstruction era.

The first thing to note about CANDYMAN: it’s fuckin scary. Like all the most iconic horror movies, this one has stuck around primarily by working incredibly well on the mechanical level of being an effective scare machine. Rose sends an innocent into a forbidden place where he creates great tension, mood and atmosphere, and sets us off balance with surreal encounters and surprises, punctuated occasionally with intrusions from the supernatural world that result in visceral, gory violence. It veers into the fantastical, but never at the expense of the grounded. The gritty on-location photography of Anthony B. Richmond (LET IT BE, DON’T LOOK NOW, THE INDIAN RUNNER) is given gothic grandeur by God-like helicopter shots of the city’s geography and a guaranteed-to-get-stuck-in-your-head organ/choir/synthesizer score by Philip Glass.

Tony Todd (NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD 1990), who plays Candyman, not only has a tremendous, commanding presence, but was actually willing to film a scene where real bees crawl around on his tongue and fly out of his mouth. This being just before the digital era, the bees that live in Candyman’s ribcage are the real deal. Rose reports that Madsen was in an actual hypnotic trance for those scenes, adding even more phantasmagorical weirdness to the proceedings.

There’s a common format of horror story, used often in ghost movies, that I’m not really a fan of. It’s the one where the heroine or hero keeps seeing horrible, weird things, but then wakes up or snaps out of it, and doesn’t suffer any consequences, just goes on with life again until something weird happens again, and then wakes up from that. Repeat ad infinitum. After it happens so many times it’s hard not to catch on and no longer worry about whatever weird shit she encounters. CANDYMAN completely upends this technique in the shit-hits-the-fan moment when Helen is approached by Candyman in a parking garage.

It happens at a time of celebration. She’s been the victim of an assault but is now out of the hospital, her thesis having taken a fascinating turn that actually put a murderer behind bars. She’s learned that photos she thought were lost have been recovered and that publishers are very interested in her and Bernadette’s work. She’s smiling and excited and right then the angry ghost whose existence she thought she’d disproven walks up to her and speaks to her telepathically.

Suddenly she’s waking up, and in any other movie that would mean maybe it was all a dream, maybe it wasn’t, but either way phew, she’s safe for the moment. Not this movie. Helen doesn’t wake up peacefully at home, but in the apartment of Anne-Marie (Vanessa Williams, NEW JACK CITY), a hard working single mother she had interviewed about the murder of a neighbor. Helen is on the floor and covered in blood, but she figures out it’s not her own. Anne-Marie’s dog is laying nearby with its head chopped off. Helen picks up the hatchet on the floor next to it. Who did this? Candyman? Is he still here?

Anne-Marie is screaming in the other room. Her baby is gone. The crib is filled with blood. She sees Helen, assumes she killed her baby, screams at her, tackles her, bangs her head against the floor. Helen can’t get her off and then, oh jesus, she swings the hatchet into her arm. And then the cops kick the door in and she’s in this woman’s home, on top of her, holding a weapon, covered in blood.

Each step of the way, as it gets more nightmarish, as she digs the hole deeper, I’m thinking okay, she’s going to wake up again.

But she doesn’t. She gets arrested. We realize we won’t be returned to safety and comfort around the time we’re watching her shakily submit to a strip search, crying helplessly about wanting a shower to clean the blood off. How the hell will she get out of this? (Spoiler: she won’t.) She begs to talk to the friendly detective who helped her when she got attacked, only to be chewed out and read her rights by him when she does. She calls her husband Trevor (Xander Berkeley, TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY) and he doesn’t answer. She has no one. Kind of like Candyman.

If you look at some of the controversies in the headlines from the last year or two it’s hard to deny that we still have a painful racial divide in the United States. Different segments of the country react very differently to, for example, the frequent police shootings of unarmed African Americans, the subsequent protests and the police response to those, even the presidency of Barack Obama and whether he is who he says he is or actually a secret Kenyan Muslim anti-American socialist, uh… whatever it is they think he is. Last summer a gun massacre committed by a white supremacist inspired a new movement against the Confederate battle flag that still flies over some Southern capitols, and there’s bitter disagreement over whether the flag used by the army that fought and died to preserve the institution of slavery represents… well, the army that fought and died to preserve the institution of slavery, or something called “Southern Pride” which they claim is separate from race and slavery even though that’s the flag they chose to use.

CANDYMAN is all about the way our traumatic racial past still haunts us in this country. It’s both literally and figuratively about the legacy of slavery. According to a story told by Professor Purcell (Michael Culkin), Candyman (who is never given any other name until the not-as-good sequel) was the son of a slave. After the civil war his father made a fortune from the invention of a machine used in the manufacturing of shoes, so young Candyman lived well, received a good education and became a sought after portrait artist for the ruling class. But this freedom and opportunity ended as soon as he fell in love with a white property owner’s daughter. Then the locals sawed off his arm, smeared him with honeycomb and burned him alive. So much for equality.

These things had improved in Chicago by 1992, but not as much as we’d like to think. A major theme of the movie is the unofficial racial segregation of modern cities. The scary place that Helen dares to go to – what in the old days would be a haunted castle or mansion – is the notoriously neglected and violent Cabrini-Green housing project. The fear is real: Rose filmed on location at the real Cabrini, having to negotiate with gang members (who appear in the movie as extras). Even the Candyman himself, Tony Todd, admitted to Fangoria at the time that he was scared while filming there. Police had told him to watch for snipers on the rooftops.

The intrusion of a white academic (or film crew) in an all black, lower income building adds a racial component to the trespassing and class tension themes of movies like THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE and THE HILLS HAVE EYES. Helen comes here unashamed to act like an anthropologist interviewing the natives. Bernadette, who is black, says she’s afraid to even drive past Cabrini-Green, and is more conscious of being a tourist there. When Anne-Marie sees the two snooping around a derelict apartment and tries to shoo them away, Helen explains cluelessly “Uh, we’re not cops. We’re from the university.”

“Well you don’t belong here, lady,” Anne-Marie scolds. “You don’t belong going through people’s apartments and thangs.” A little later she says, “You know whites don’t ever come here ‘cept to cause us a problem.” Bernadette gives Helen a look like “See?”

There’s a parallel here to that defensiveness and resentment that many white people feel because they don’t consider themselves racist but assume other people think they are, or that people connect them to the crimes of previous generations. The opposite of white guilt. Helen keeps finding herself in these situations where it looks like she did something horrible, but as far as she remembers she’s innocent.

“No matter what’s going wrong,” she says, “I know one thing. That no part of me, no matter how hidden, is capable of that!” And she may be right. It depends how you interpret the movie.

To be fair, Helen is not completely unaware of her white privilege. After being assaulted in Cabrini she points out the disparity in the way the system values white crime victims vs. black ones. “Two people get brutally murdered, and the cops do nothing,” she says, “Whereas a white woman goes in there and gets attacked, and they lock the place down.”

(“But all lives matter!” interject your most frustrating Facebook friends, missing the point.)

Helen being an outsider here is actually a mirror image of Candyman’s history. When his ashes were spread across these grounds he was the minority, doomed by his relationship with a white woman. Now it’s the other way around. In fact, he and Helen’s fates seem to be intertwined. “IT WAS ALWAYS YOU HELEN” he says, and writes on the wall. The graffiti desecrates an old mural depicting the white land owner’s daughter whose love led to the lynching of Candyman, and she looks just like Helen.

In horror tradition this resemblance means that Helen may be a reincarnation of Candyman’s lost love (see also THE MUMMY and various versions of DRACULA, including BLACULA). But on another level it shows how the events of the past echo through today. Generations later the white land owner’s family is still well off, living on the good side of the L-train, owning a condo, going to graduate school, maybe not even conscious of being born into opportunities that the residents of Cabrini-Green were not.

This imbalance is underlined by Helen’s discovery that her building is identical to Cabrini-Green. Underneath they’re the same, but Helen’s is plastered over and repackaged as condominiums. Anne-Marie’s is covered in graffiti, controlled by gangs, and intentionally geographically segregated from the white neighborhoods.

So these are the conditions and injustices that still exist in the wake of our history. Now what do we do about them? Maybe one thing we have to do is get rid of the myths we stubbornly hold onto about each other. CANDYMAN is also about the immortality of stories. He comes after Helen because she threatens the power of his legend, in part by convincing a kid named Jake (DeJuan Guy, ONE MAN’S JUSTICE) that Candyman isn’t real. The killer needs a “congregation” to believe in him in order to continue. He exists not as a life, but as a story. “It is a blessed condition” he says, “to be whispered of on street corners, to live in other people’s dreams, but not to have to be.”

He’s a legend. A lie. And his plan is to turn Helen herself into a racially divisive myth: the white lady who attacks innocent black women, chops them up or kills their dogs and steals their babies. He manages to turn her into a reverse of himself: an innocent white woman burned alive by a mob of black people (though their ignorance is different from the white mob; they’re after Candyman and don’t know that Helen is inside the bonfire as well).

It is (SPOILER) not a happy ending. Helen ends up dead (and with her hair burnt off). Trevor attends the funeral not only with his young student mistress, but also his pompous friend and Helen’s academic rival Purcell. The guy she said she’d “bury.” I guess that didn’t work out.

But then Anne-Marie, Jake and what seems to be the entire Cabrini-Green community show up, and they bury Candyman’s hook with her. Could this symbolize a chance to put the past behind us? Maybe the racist superstitions that Anne-Marie has to struggle against, that caused city planners to strand the poor on the other side of the tracks, that inspired the shooter in Charleston, that cause some of your white relatives to call young black men “thugs,” are like Candyman himself. They’ll fight viciously for survival at a time like this, when massive change is on the horizon, when it seems like people are about to stop believing in them. But eventually, hopefully, they’ll fade away, dissipating like a swarm of bees.

November 1st, 2018 at 5:14 pm

Even though I know it’s just a film, it’s a testament as to how effective it is that there’s no way I’m ever saying you know what even once let alone five times into a mirror.