I don’t like to say I have a favorite movie. There are too many great ones that I love for too many equally meaningful-to-me reasons. But if I had to choose one, like if you had to register your favorite movie with the government or something, maybe it would be DIE HARD. I wrote a piece about it before, but that was 16 years ago, I was a different person then, and it’s embarrassing to me. So let me try again.

I don’t like to say I have a favorite movie. There are too many great ones that I love for too many equally meaningful-to-me reasons. But if I had to choose one, like if you had to register your favorite movie with the government or something, maybe it would be DIE HARD. I wrote a piece about it before, but that was 16 years ago, I was a different person then, and it’s embarrassing to me. So let me try again.

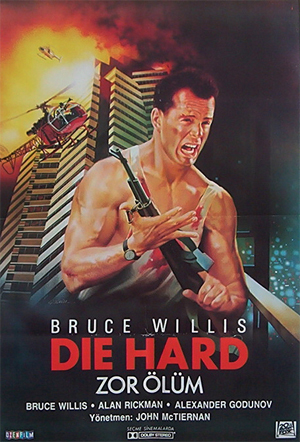

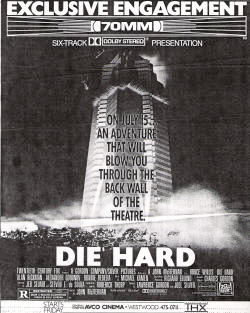

Many of the reasons I love DIE HARD are self evident. By now most people have caught on to the fact that it’s an extremely well made, ridiculously entertaining popcorn masterwork. The story is so perfect and elemental that it became a template, a name for a reliably entertaining subgenre of action movies. This is a testament to the genius of the setup by Roderick Thorp in his novel Nothing Lasts Forever, its remolding by screenwriters Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza, and its precise cinematic execution by director John McTiernan, cinematographer Jan de Bont, editors John F. Link and Frank J. Urioste, composer Michael Kamen, etc. They crafted a pitch perfect introduction of this character (based around the charm and humor of Bruce Willis) and unrolling of the sinister plot he’s about to crash head first into. And then it escalates into spectacular crescendos – the explosion in the elevator shaft, the desperate leap from the roof and bare-foot-kicking-through of the window – that, in their somewhat grounded context, continue to feel enormous even after movies (including its four sequels) have gotten bigger and bigger for nearly three decades. In retrospect it wasn’t the amount of C-4 but the placement of it that caused the ads to vow it “WILL BLOW YOU THROUGH THE BACK WALL OF THE THEATRE.”

Unlike some of my other favorite movies, DIE HARD does not have a clear underlying message that speaks to me. I don’t consider it a political movie at all. Maybe that’s good, because it’s a unifying movie, easy for people of all stripes to get behind and enjoy together. But there’s definitely a bit of good natured class subtext here in the midst of its New York over L.A. favoritism. John McClane represents a no nonsense, hard-working man. From what we know he’s a good cop, putting himself on the line to make the world better, but at the expense of his most important relationships. He chose chasing his “six month backlog of New York scumbags” over being with his wife and kids as they build a new life on the west coast. And as punishment Holly changes back to her maiden name Gennaro, a severing of the patriarchal tradition of surnames.

When he comes to L.A. McClane walks around with a look of “can you believe this shit?” bemusement. He looks suspiciously at a girl in tight pants giving her boyfriend a four-limbed hug. He seems embarrassed to be picked up by a limo, and doesn’t even know how it works. “Okay Argyle, whadda we do now?” He ends up sitting shotgun, refusing to play along with the traditional Driving Miss Daisy power dynamics of driver and passenger. (Admittedly the McClane family has a maid who seems to be familiar with John, so he’s not pure in his status as the Common Man.)

When he comes to L.A. McClane walks around with a look of “can you believe this shit?” bemusement. He looks suspiciously at a girl in tight pants giving her boyfriend a four-limbed hug. He seems embarrassed to be picked up by a limo, and doesn’t even know how it works. “Okay Argyle, whadda we do now?” He ends up sitting shotgun, refusing to play along with the traditional Driving Miss Daisy power dynamics of driver and passenger. (Admittedly the McClane family has a maid who seems to be familiar with John, so he’s not pure in his status as the Common Man.)

At the Nakatomi Corporation Christmas party he sees various office sex and drugs going on, and he meets douchey Harry Ellis, the guy in charge of international development who’s clearly snorting coke and sniffing around married Holly Gennaro. He makes a lame attempt to seduce Holly by talking about wine and brie, and makes way too big of a deal about the Rolex that the company bought her. She shuts the topic down because she knows John won’t be impressed by it. Good for him.

I think these people and this world set off McClane’s alarms not because he’s a prude but because he senses the general unfairness here, that he works way harder at a much more dangerous job and he suffers for it, losing his wife and kids. Meanwhile these people just make money for some international conglomerate and they get to fuck around and party, wear shiny watches, ride in limos.

Grueber and his gang might as well be an international conglomerate themselves. Their work ethic seems stronger than Ellis’s – they’re presented as very professional, storming from a truck to the building like elite space marines marching through an airlock – but Grueber is a parallel to Nakatomi CEO Joe Takagi, pointing out that he owns two of the same expensive suits. Though Grueber and his team act like some kind of anti-capitalist guerrillas, that turns out to be a cover. They’re thieves. They want all the money in the safe, that’s all. This is just an extra-hostile takeover.

It’s kind of funny that DIE HARD is the gold standard for ’80s action movies but also has kind of a meta theme saying that its “real world” is not like the mythology of the movies. References are made to Rambo and Arnold Schwarzenegger, and McClane not being them. He also likes to sarcastically compare himself to the heroes of old westerns, and nicknames himself after the singing cowboy Roy Rogers. When Grueber misnames the stars of HIGH NOON it reveals him as out-of-touch with America.

But there’s another kind of fantasy going on. When FBI agents Johnson and Johnson are choppering in, “Big Johnson” yells “Just like fuckin’ Saigon, eh slick?”

“I was in junior high, dickhead,” says Little Johnson, not interested in that fantasy.

The opulent Nakatomi office includes an indoor waterfall and artificial plantlife, a sign of the decadence of the Los Angeles/Nakatomi lifestyle. Who needs to go out in nature when you can manufacture a chunk of it inside your 40 story skyscraper? Later, when the top of the building has exploded, a dirty, wounded McClane stumbles through the fake plants and we see them in a different light. The fancy office decorations have become a simulacrum of the jungle war zone that Agent Johnson pines for.

One of the key relationships in the movie is between McClane and Sergeant Al Powell, the patrolman he flags down using a dead body and talks to over the radio. Powell may have one day been on a track to be a supercop like McClane, but he took himself off the streets after accidentally shooting a kid who he saw with a toy gun. Remember, back then it was real different, it was considered a huge error for a cop to accidentally shoot an unarmed person. It was considered something to be ashamed of and try to prevent, rather than the thing they have now where 100% of all police shootings are for sure justified and rallied behind by all police officers and conservatives no matter what and how dare you not honor Al Powell’s brave sacrifice the kid was lurching at him he was just doing his job where were the parents, etc.

Since then Powell has lapsed, perhaps grown a great love for Twinkies, would not look good in McClane’s tank top. McClane does a bit of desk-shaming, implying that real cops shouldn’t be pushing pencils or whatever, and at the end we’re definitely supposed to take macho pride in Powell getting the confidence to shoot somebody again (this time an armed adult trying to kill somebody… phew). But here’s something to take note of: right after Powell shoots Karl, Argyle crashes his limo out of the garage and is driving toward them, and everyone reacts like it’s a new threat. McClane has to tell Powell that Argyle is with him, averting the potential of another innocent young black man killed by mistake. But when the car is driving at him, Powell holds his gun up. He’s ready, but he doesn’t shoot, he doesn’t even aim, he takes a moment to assess the situation. Good job, Sergeant.

I think McClane and Powell get along because they quickly sense a lack of bullshit in each other. They’re the only two guys in on this whole mess who have their heads on their shoulders. Powell only knows McClane over the radio, but vouches for his character, to no avail. At the end, when they meet face to face for the first time, they immediately recognize each other, smile and hug. It’s funny, this is kind of a thing we have more in the modern world, people who sort of get to know each other without occupying the same physical space. McClane is an analog man in a digital world, but he predicted online relationships.

I wasn’t gonna say anything, but I’ll say it. My dad died earlier this month. A couple days later I decided to watch DIE HARD in his honor. We used to love watching Moonlighting, and Bruce’s persona was the kind of guy you wished you could be back then: a cocky smartass nobody could keep up with, like Bugs Bunny, who was also liable to bust out into some tunes at any moment, like a Blues Brother. Obviously John McClane sent that appeal into overdrive. But DIE HARD makes me think of my dad and me not just because it’s a movie we enjoyed together long ago but because, I now realize, it’s about a certain type of masculine stubbornness that he had and I have, for good and bad. My dad spent his life doing things out of a sense of duty to his family and the things he felt a man was supposed to do, going way out of his way to provide and rarely if ever complaining about the toll it took on him. For him it meant getting up at the crack of dawn to drive into the city and then take a long ferry ride to the shipyard where he worked every day, then coming home and then often running out to do things for my mom. He was notorious for driving to multiple stores in a single-minded pursuit of every last thing on a shopping list.

I wasn’t gonna say anything, but I’ll say it. My dad died earlier this month. A couple days later I decided to watch DIE HARD in his honor. We used to love watching Moonlighting, and Bruce’s persona was the kind of guy you wished you could be back then: a cocky smartass nobody could keep up with, like Bugs Bunny, who was also liable to bust out into some tunes at any moment, like a Blues Brother. Obviously John McClane sent that appeal into overdrive. But DIE HARD makes me think of my dad and me not just because it’s a movie we enjoyed together long ago but because, I now realize, it’s about a certain type of masculine stubbornness that he had and I have, for good and bad. My dad spent his life doing things out of a sense of duty to his family and the things he felt a man was supposed to do, going way out of his way to provide and rarely if ever complaining about the toll it took on him. For him it meant getting up at the crack of dawn to drive into the city and then take a long ferry ride to the shipyard where he worked every day, then coming home and then often running out to do things for my mom. He was notorious for driving to multiple stores in a single-minded pursuit of every last thing on a shopping list.

That’s not the same thing as saving a bunch of hostages from gunmen, but it comes from a similar instinct. McClane doesn’t really want to deal with this shit, but this shit is happening, so he has to do it. He knows what he has to do and he does it and when it gets hard he doesn’t give up.

If my dad was working on something around the house he would not stop until he was done, even if he didn’t know what he was doing. If you asked him to help fix something and he tried to do it but was having trouble, and you eventually told him to forget about it so you could try to figure it out yourself, too bad. He was in for the long haul. This is also John McClane. The police want him to step aside, the FBI want him to step aside, but he knows he’s the only one that can get it done, and he’s not gonna stop.

Deputy Police Chief Dwayne T. Robinson, douchebag negotiator-with-terrorists Harry Ellis and FBI agents Johnson and Johnson are all dealing with their own stubbornness. They think it has to be done their way and hate McClane for doing it his way. Even after McClane has succeeded, Robinson runs up to lecture him about it. The difference is that these other guys are just stroking their egos, assuming they know everything. McClane is in the middle of it and knows what he’s talking about. He’s using his expertise correctly. He is in the right and he will not die easy and there’s something primally manly about that, I think it appeals to our instincts. Many women deeply love DIE HARD too, of course, but I think what I’ve described here is part of the reason why John McClane speaks to some men, myself included, as some sort of model of masculinity.

But the mistake some people make is to get too nostalgic, too stuck in their ways, to say this is how it was in the old days or this is how I was raised, so this is how I am. This is how men behaved in my house and in my movies, so that’s that. Well, that’s not what McClane does. He’s a representation of The Old Days and people think of him as being stuck in his ways, but in fact he grows. After the powerful scene where he tells Powell over the radio to apologize to Holly for him if he doesn’t make it – sort of the DIE HARD version of Rambo’s emotional breakdown at the end of FIRST BLOOD – McClane has a different attitude toward their relationship. It’s a big moment when Holly is meeting Powell at the end and calls herself Holly McClane again. But it’s arguably more significant that John introduces her as Holly Gennaro. He’s not gonna keep having this argument, even in his great moment of triumph when he could probly get away with it. Instead he tries to respect her wishes. Even John McClane can compromise when he wants to be nice to someone else.

My dad wasn’t against changing. My mom never let him forget that he voted for Reagan, but he became a Democrat, and hated Bush with a fire even deeper than my own. We would sit around and rant to each other for hours. He grew up in a cabin with an outhouse, and a hole that he’d punched in one of the walls when his parents were fighting. As an adult it bothered him that so many poor people voted for the party that openly worked against them.

When I was growing up it was common to use homophobic slurs, but I remember when I had a realization that it was wrong and I called him on some joke he made, and it actually got through to him and he stopped doing it. I think it’s important to remember the old ways, but you have to question them too. Sometimes they’re holding us back. I bring this up because I’ve seen people into the same so-called “manly movies” as me who use them as a crutch and an excuse to be assholes, to define masculinity only by its worst traits, and then hold that up as an ideal. No. Fuck you. That is an incorrect reading of the text.

For today DIE HARD is my favorite movie, and let the record show that this is not that thing where I’m just nostalgic for the feeling it gave me when I first saw it. No, the nostalgia is more like pride that I got it so right back then. I imagine as I get older it will continue to speak to me in new and growing ways. One of those ways, now, is to help me remember my dad, recognize how I’m like him, how I should be less like him, how I should be more like him. That’s what you do. You acknowledge your weaknesses, emulate what’s great and try to keep improving. Thank you, dad. For DIE HARD, and for everything else.

* * *

And Merry Christmas everyone. Sorry if I made you cry. Thank you for sharing in this journey with me. You’ve all been an important part of my life for a good decade and a half now. I know that’s no small shakes and I am truly grateful. And so, as Tiny Tim said, “A Merry Christmas to us all; God bless us, everyone; yippee ki yay motherfucker! Part 2 is also quite good.”

December 23rd, 2015 at 1:53 pm

Wow. I’ve always been a fan and, obviously, I love to read you when you review action movies, but this got REAL.

Sorry about your loss.