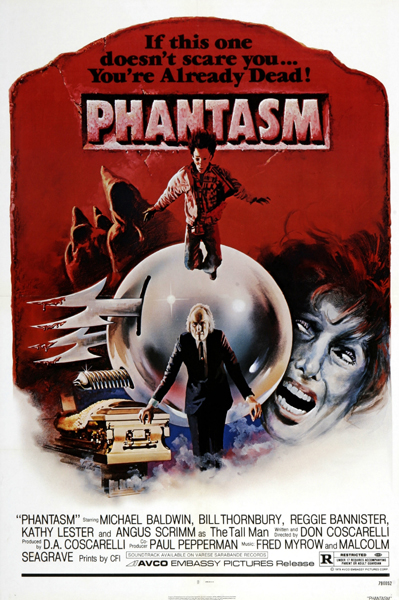

PHANTASM stands alone in American horror – even of 1979 – because of its emphasis on the fuckin weird. Many horror movies are about the fear of a dude with a knife or ax. That makes sense. We know his immediate goal and why it threatens us. Or sometimes it’s supernatural, or it’s a monster. That brings in the fear of the unknown, but we still sort of know most of the time. It’s gonna bite us.

PHANTASM stands alone in American horror – even of 1979 – because of its emphasis on the fuckin weird. Many horror movies are about the fear of a dude with a knife or ax. That makes sense. We know his immediate goal and why it threatens us. Or sometimes it’s supernatural, or it’s a monster. That brings in the fear of the unknown, but we still sort of know most of the time. It’s gonna bite us.

But PHANTASM creeps us out by giving us a bad guy our minds aren’t used to wrapping around: a mean old man at a funeral home who is unusually strong, bleeds yellow, his body parts can turn into bugs, he commands deadly flying metal orbs, and he steals bodies from graveyards and crushes them into weird little dwarves in Jawa robes who do his bidding. It’s a scheme we have seen in less than 50 movies in the entire history of cinema up until this point so it isn’t worn out yet.

It doesn’t hurt that the hero, Mike, is a kid, a loner orphan who spies on his cool older brother Jody because he (correctly) suspects he’s gonna ditch him again. He accidentally sees some of the weird shit going on in the funeral home but when he tries to tell his brother it has the feel of the kids who, to make life more interesting, start saying that their neighbor is a witch or the house at the end of the street is haunted. So you can’t blame Jody for not believing him. But this movie, although completely deadpan and never outwardly comedic, has a hilarious way of dealing with that. First Jody suggests what Mike saw was “probably just a gopher in heat.” Later he asks “Are you sure it wasn’t that retarded kid Timmy up the street?” Then Mike gets chased by the Tall Man, slams a door on his hand, and slices off his fingers. The fingers are alive though and try to crawl away like worms, but he catches one in a box and brings it to his brother. Jody peeks into the box. Is it still in there? Is it still alive? Yes, it wiggles around. He shuts the box. “Okay, I believe you.”

It doesn’t hurt that the hero, Mike, is a kid, a loner orphan who spies on his cool older brother Jody because he (correctly) suspects he’s gonna ditch him again. He accidentally sees some of the weird shit going on in the funeral home but when he tries to tell his brother it has the feel of the kids who, to make life more interesting, start saying that their neighbor is a witch or the house at the end of the street is haunted. So you can’t blame Jody for not believing him. But this movie, although completely deadpan and never outwardly comedic, has a hilarious way of dealing with that. First Jody suggests what Mike saw was “probably just a gopher in heat.” Later he asks “Are you sure it wasn’t that retarded kid Timmy up the street?” Then Mike gets chased by the Tall Man, slams a door on his hand, and slices off his fingers. The fingers are alive though and try to crawl away like worms, but he catches one in a box and brings it to his brother. Jody peeks into the box. Is it still in there? Is it still alive? Yes, it wiggles around. He shuts the box. “Okay, I believe you.”

And that’s all we need to transition from the “nobody will ever believe me” part of the story to the “let’s hunt it down and kill it” part.

The budget is tiny, but they were smart about how to make the cheesy effects work. They’re so surreal they have kind of a shock factor – you’re not used to a metal sphere shooting at your head. And the weird shit happens pretty frequently, there’s not as much sitting around talking as you might expect. The repetitive, sort of Goblin-esque keyboard score adds to the eeriness.

Even at the climax it doesn’t turn into standard horror. The Tall Man has a portal into another world, the kid’s sidekick (Reggie Bannister) is a middle-aged, guitar playing ice cream truck driver who is a survivor of male pattern baldness, and the kid uses such horror-fighting techniques as attaching a bullet to the end of a hammer and hitting it. Not exactly by-the-numbers cat-and-mouse-shit.

This is a truly inventive and enjoyable little movie, there’s not really another one like it. But I’m not sure what Phantasm means.

http://youtu.be/Ns_PWwd4LYs

October 7th, 2016 at 5:33 am

Caught the remaster of this over at the Amazon VOD. I’ve only seen it maybe once prior, so I don’t have well-grooved memories of how crappy the old, pre-remastered version was, but it certainly looks and sounds pretty good. I did not read up to remind myself of the plot or spoilers, so pretty much all I remembered was Angus Scrimm, plus the ball, plus the dwarves. I had no recollection of the basic plot or climax or the relative screen time of the aforementioned Scrimm, ball, or dwarves.

SPOILERS for a 35+ years-old film

Vern is right. First and foremost, this film traffics in the weird, weird, weird. It has a very disjointed, choppy feel. Aside from the totally bonkers core mythology and iconography (the ball, dwarves, yellow-goo-bleeding, tall man, the alternate world), there another of other weird things that just feel off and incoherent. The plot adheres to a fairly conventional structure and achieves a resolution, but the journey is full of inconsistencies, inexplicable moments, and dream-like doubling back. Scenes cut away too soon or are intercut weirdly. Characters show up in places in ways that defy our sense of space and time–and, thus, probably, also the laws of physics. Mike is always right behind his brother, never detected, and presumably on foot in at least some of these instances. People complain that they can’t see some other character “anywhere,” then, without moving, they suddenly do see the character. The Tall Man seems essentially unkillable and able to project himself to different places in space. He plunges down a “1000 foot” mine shaft and is then sealed in by a couple of good sized rocks. Reggie inexplicably shows up at the mortuary looking like a million bucks when his most recent previous scene would have us believe he was a goner, or at least in serious peril and very rough shape (He also casually reassures us that that Mike’s cousin and sister who abducted shrieking in a dwarf-filled VW managed to escape off-camera). With a few exceptions, the main characters seem to exist mostly in a world all their own, rarely intersecting with anyone other than the three other principal characters or the dwarves It’s very clear who is in the foreground, and the only things in the background are that synth score and the physical settings.

The reveal that this has been a dream clears up all of this and elevates the film to a kind of beautifully trippy waking nightmare piece of art. Although those weird incongruities and logic gaps are reframed as completely explicable instances of garden variety nightmare illogic. Moreover, Mike’s stalker-like clinginess toward Jody, and the running theme that Jody will not allow Mike to follow him where he is going, take on a new, poignant significance. In large part, the nightmare represents Mike wrestling with his grief and denial. And then, of course, the obligatory last scene gotcha.

My guess is that a substantial proportion of the film’s narrative and visual (space/time) illogic was intentional and due to budget constraints or just continuity flubs and difficult choices in making a coherent film out of the available footage. But the conceit that this has all been a nightmare ends up making all that stuff work in its favor. This is a weird and mediocre film that is elevated to greatness by its imagery, mythology, and the covering explanation that all its seams and WTF moments can be reframed as part and parcel of the phenomenology of lucid nightmares.