In North America, February is Black History Month. I mean, it’s debatable how real of a thing it is. Every year we note that black history oughta be taught in other months also, and of course you got the “why is it the shortest month?” jokes. The U.K. musta foreseen that, ’cause they have theirs in October. But really 28 days of Black History Month is 21 more than the original “Negro History Week,” which was celebrated in February because of the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. It was intended to encourage teaching about African-American history in schools, which I guess did not go over great when it started in 1926. But 50 years later an expanded month long version was officially recognized by the government. So suck on that, 1926.

In North America, February is Black History Month. I mean, it’s debatable how real of a thing it is. Every year we note that black history oughta be taught in other months also, and of course you got the “why is it the shortest month?” jokes. The U.K. musta foreseen that, ’cause they have theirs in October. But really 28 days of Black History Month is 21 more than the original “Negro History Week,” which was celebrated in February because of the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. It was intended to encourage teaching about African-American history in schools, which I guess did not go over great when it started in 1926. But 50 years later an expanded month long version was officially recognized by the government. So suck on that, 1926.

I don’t know what goes on in the schools today, but in the world of grownups it seems like the month isn’t that meaningful to most people. It seems more common to see it used for flimsy, borderline offensive corporate promotions than for any kind of legitimate attempt to fulfill the goal of bringing awareness to aspects of American and world culture that don’t tend to get enough recognition.

Obviously I don’t believe in confining learning about anything to one month. Except maybe Christmas decorations. But in the spirit of the tradition’s good intentions I’m gonna use it as an excuse to educate myself a little bit. I’ve had it on the backburner forever to rewatch all of Spike Lee’s movies, and recently the WOLF OF WALL STREET “glorification” arguments had me wanting to re-watch MENACE II SOCIETY and BOYZ N THE HOOD as a study in showing vs. preaching. But I would feel like an asshole doing either of those things in February, as if I thought they represented the entire history of black film. But then again, how much do I really know about the subject outside of blaxploitation and those late ’80s, early ’90s breakouts?

I knew there had to be more to the history of black film than what I’m familiar with. I have to admit, if somebody says “black film” the first person that comes to mind is still Spike Lee. Then you got the more commercial ’90s guys, the Hughes Brothers and John Singleton. You have the DIY comedians like Robert Townsend and Keenan Ivory Wayans. Today you have Lee Daniels, Steve McQueen U.K. and Tyler Perry, a few studio guys like F. Gary Gray, and up and comers like Ryan Coogler, Scott Sanders, Ben Ramsey. This is hardly a complete list, but it’s probly longer than what alot of people could come up with off the top of their head. And these are interesting guys, but not enough to represent the entirety of the black experience, or more importantly to get past the expectation that they should try to do that.

So I did some reading. I was happy to find a whole world of black filmmakers out there that I had missed. This list is a good resource I found. Idrissa Ouedraogo (YAABA) is one of the most prolific African directors, for example. And there’s Ousmane Sembene (BLACK GIRL, XALA) and Djibrtil Diop Mambety (TOUKI BOUKI), both of Senegal. In the U.S. I forgot about arthouse and indie people like Haile Gerima (ASHES AND EMBERS, SANKOFA), Julie Dash (DAUGHTERS OF THE DUST), Carl Franklin (ONE FALSE MOVE), Kasi Lemmons (EVE’S BAYOU). And I definitely gotta get up on Charles Burnett, whose KILLER OF SHEEP has been recommended to me a million times and which I promise I will see soon.

But of course this is outlawvern.com so if there’s a way I can broaden my horizons while also seeing some guns and punching then that’s gonna be my preference. So I decided that throughout this month what I’m gonna do is try to check out black action stars or filmatists that I previously didn’t know about or didn’t pay much attention to.

But of course this is outlawvern.com so if there’s a way I can broaden my horizons while also seeing some guns and punching then that’s gonna be my preference. So I decided that throughout this month what I’m gonna do is try to check out black action stars or filmatists that I previously didn’t know about or didn’t pay much attention to.

Did you know there used to be something called “race films”? You guys are aware of my affection for the blaxploitation era, and my respect for the DIY ethics of Melvin Van Peebles, Rudy Ray Moore and Fred Williamson. But they weren’t the beginning. We’re talking about as far back as the teens and through about 1950 there was a whole industry of movies made for black audiences, with all black casts. Some of them were even made by black producers, writers and directors. The novelist Oscar Micheaux started a company with all black filmmakers and directed his own movies starting in 1919.

These were mostly made outside of the Hollywood system, considered some of the first independent films. Despite segregation they sometimes played in white theaters, but mostly as matinees or midnight shows. So aside from dramas like the ones Micheaux made and Paul Robeson starred in, alot of them were typical b-movies, westerns and gangster films.

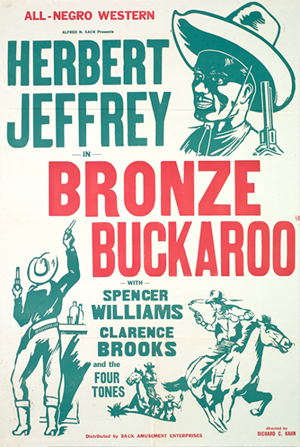

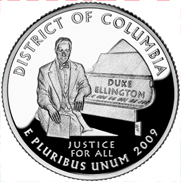

So I took a look at some of these all-black westerns and the one that jumped out at me was THE BRONZE BUCKAROO, because the star, Herb Jeffries, was a singer who joined Duke Ellington’s band around the time of this movie. That puts him in an elite group of movie stars who know a guy who ended up on a quarter. Also it puts him in the then-popular category of singing cowboys, but coming from a jazz background. A cowboy with soul.

So I took a look at some of these all-black westerns and the one that jumped out at me was THE BRONZE BUCKAROO, because the star, Herb Jeffries, was a singer who joined Duke Ellington’s band around the time of this movie. That puts him in an elite group of movie stars who know a guy who ended up on a quarter. Also it puts him in the then-popular category of singing cowboys, but coming from a jazz background. A cowboy with soul.

(This is actually Jeffries’ third singing cowboy vehicle, after HARLEM ON THE PRAIRIE and TWO-GUN MAN FROM HARLEM, but I chose it because it was on a collection called Treasures of Black Cinema hosted by Richard Roundtree. Also “The Bronze Buckaroo” became Jeffries’ nickname from then on, so it must be important.)

(And by the way, despite those titles I don’t think Jeffries is from Harlem. He was born in Detroit, anyway.)

Jeffries’ character Bob Blake dresses kinda like the white singing cowboys such as Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. The guys in his posse just dress like normal cowboys with plaid shirts and baggy, worn out jeans. But Bob dresses all fancy. A neatly tailored outfit, form-fitting, with decorative embroidery and shit. Pin-stripe down the side of the pants, tucked into the boots, big white hat, gloves, show-offy belt and holster. Actually, he dresses kinda like Cowboy Curtis. It’s a different vibe though, ’cause he has short hair and a neat mustache. More of a suave Cab Calloway type of look.

The story is pretty minimal, even for a movie that’s less than an hour long. Pretty Betty Jackson (Artie Young, who was later a dancer in mainstream movies like SKIRTS AHOY! with Esther Williams, but always uncredited) is upset that her dad got killed and her brother (who used to work with Bob) has gone missing. So Bob and the boys go looking for the brother, who we quickly realize is in trouble with some assholes trying to steal his land.

The boys don’t even have to do much tracking, they just go to a saloon and happen to get into a brawl with these dicks. One guy forces Dusty to smoke four cigars at the same time and Slim to drink fou shots at the same time. In separate glasses, but he’s not allowed to spill.

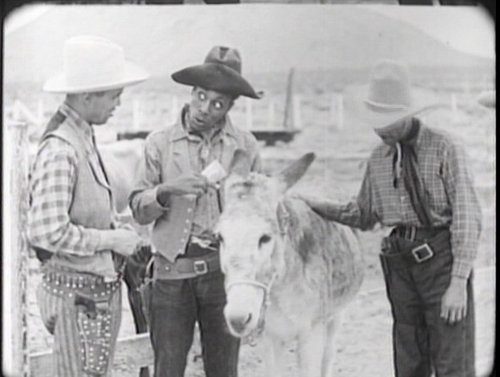

There’s a comedic subplot about how this guy named Slim Perkins (Broadway actor and lyricist F.E. Miller, who wrote another Jeffries movie called HARLEM RIDES THE RANGE) uses ventriloquism to trick Bob’s dim-witted buddy Dusty (Lucius Brooks of Jefries’ backup singers The Four Tones, who are all in the movie) into buying a “talking mule.” This is historically interesting because Dusty is a big dummy and does some of the kind of bug-eyed mugging that was a black stereotype of the time:

But it’s different in this. In movies where a guy like this is the only black character it’s horribly offensive. But in this movie everybody else is black: the smooth hero, the beautiful damsel, the corrupt land baron, the thuggish enforcer, the bartender, the people in the bar, everybody. And keep in mind this is 1939. Over in the studio system the most prominent black role that year was Hattie McDaniel as a maid on a southern plantation in GONE WITH THE WIND.

In the context of this movie Dusty doesn’t seem so upsetting, he’s just a comic relief character. If it was today he could be Kevin Hart or Mike Epps or somebody doing a broad comedic role. It shows how we wouldn’t have to care quite as much about stereotypes if there was a wider range of representation. Then there wouldn’t be as much pressure for every performer or artist in a minority group to uplift and inspire their people every time. And if they wanted to joke around or put on a dress nobody would point fingers of shame at them.

Also, by the way, Dusty gets to outsmart Slim at the end and kill the bad guy. Though he talks to his gun like it’s a person both before and after he does it.

Now, I should mention that there’s a tap dancing scene, and singing at the saloon. This is also touchy territory by modern standards since we know black entertainers at the time were pigeon-holed as minstrels dancing for the white man. But the thing is, this singing was what the white people were doing too. It was a requirement of the genre. These guys just follow the fomula, but arguably are better at it, or at least are able to do it in a different style. And since these movies were produced for black audiences they have none of the subtext of subservience. It’s just enjoying some music and dancing in the Old West. Cowboys gotta dance too, you know.

The singing could definitely be considered Badass Juxtaposition. It doesn’t take away from Bob’s manliness. There are I think the same amount of action scenes as musical. There’s a bar brawl with a boxing style square off, and a big messy shootout in the desert, bad guys up in the hills, people hiding behind rocks, bangs and puffs of smoke going off everywhere.

If I had done more pre-rental research I would’ve tried to pick one of the westerns done by a black director and crew. I can’t find anything about the background of writer/director Richard C. Kahn, but it seems the production company, Sack Amusements, was a white-owned company that specialized in movies for black audiences.

Instead of Monument Valley it was filmed in Apple Valley, California on Murray’s Dude Ranch, which was owned by black businessman N.B. Murray. Jeffries filmed four westerns there, and it was also a popular resort, especially for black celebrities like Lena Horne, Joe Louis and yes, Hattie McDaniel (and also Clark Gable). It was later purchased by the actress and singer Pearl Bailey.

One thing that’s interesting about Jeffries, his mother was Irish and he had some French and Italian in him too. In modern photos (he’s still alive, and over 100 years old) he just looks like a white dude to me. In those days when it might’ve been beneficial to him to play up his whiteness he wanted to be in all black jazz groups, so he actually wore makeup to look darker.

One thing that’s interesting about Jeffries, his mother was Irish and he had some French and Italian in him too. In modern photos (he’s still alive, and over 100 years old) he just looks like a white dude to me. In those days when it might’ve been beneficial to him to play up his whiteness he wanted to be in all black jazz groups, so he actually wore makeup to look darker.

Later he showed up on an episode of The Virginian, he directed a movie starring his burlesque performer wife Tempest Storm, he showed up in the William Smith biker movie CHROME AND HOT LEATHER and the Jack Palance movie PORTRAIT OF A HITMAN. He was all over the place.

So in a way maybe my first attempt at a Black History Month themed review has already subverted the whole thing. Here is a black film pioneer who walked right across racial boundaries and defied categorization. He could play white or black, jazz or country. He recorded tribute albums to both Nat King Cole and Bing Crosby, for crying out loud. To me his singing cowboy songs sound more soulful than the white dudes were doing, but listening to him on Spotify right now I gotta say he sounds like a white lounge singer even doing the disco version of his hit “Flamingo.” He was a pre-post-racial singer and actor. The Vin Diesel of the ’30s, but with crooning instead of breakdancing.

Like Michael said, it don’t matter if he’s black or white. He’s Herb Jeffries, is the important thing.

Anyway, I’m glad to know about him and his movies now. Thank you, month of February.

February 7th, 2014 at 12:56 am

Which should I see first, this or PAINT YOUR WAGON?